On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the world pauses to remember the 6 million Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust and the millions more who were persecuted and killed by the Nazis and their collaborators. Most importantly, we honor the survivors, whose personal experiences continue to inspire.

Ellen Germain, the Special Envoy for Holocaust Issues at the State Department, said, “International Holocaust Remembrance Day forces us to reflect on the magnitude of the Holocaust and its lesson about what can happen to a society when hate goes unchecked.”

Descendants of Holocaust survivors who currently work for the U.S. Department of State said stories about family members who escaped death shaped their lives and career choices.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken, the stepson of a Holocaust survivor, has said that his stepfather’s “story made a deep impression on me. It taught me that evil on a grand scale can and does happen in our world — and that we have a responsibility to do everything we can to stop it.”

International Holocaust Remembrance Day commemorates the day the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination camp in Poland was liberated in 1945. Here are the stories of three descendants of Holocaust survivors whose relatives’ history influenced their decision to choose a career in international affairs and diplomacy.

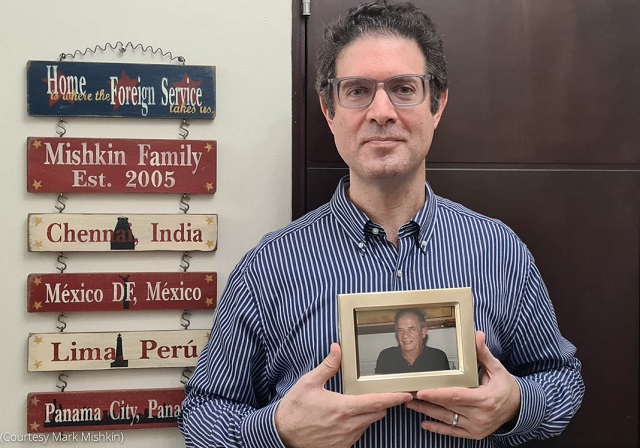

Mark Mishkin, U.S. Embassy, Panama

Mark Mishkin’s grandfather, Samuel Goldberg, survived Auschwitz-Birkenau. “Holocaust issues are more than just a vague human rights concern for me; they’re deeply personal,” said Mishkin, a foreign service officer.

He said his grandfather recalled seeing smokestacks in Auschwitz operating all night long. He discovered later that all the Roma in the camp were killed and burned that night.

“He looked up to God and asked, ‘All these people committed the same ‘crime’ that they should be burned?’” Mishkin said. The “crime,” according to the Nazis, was being Roma.

Mark Mishkin holds a photo of his grandfather. (Courtesy Mark Mishkin)

Mishkin said his grandparents’ experience and love for the United States motivated him to work for the State Department. “My profound appreciation for all that America has done for my family pushes me every day to do my best work.”

Jonathan Shrier, U.S. Embassy, Israel

Jonathan Shrier is a descendant of a family rescued by diplomats in the Holocaust. His father, grandparents and great-grandmother escaped from Poland to the United States with help from diplomatic officials from several nations. Shrier’s grandfather had a friend at the Swedish embassy in Vilnius, Lithuania, who pointed them toward Japanese Consul Chiune Sugihara and Dutch Honorary Consul Jan Zwartendijk in Kaunas, Lithuania.

Jonathan Shrier lights memorial candles on International Holocaust Remembrance Day 2021. (U.S. Embassy Jerusalem/David Azagury)

Sugihara and Zwartendijk issued the “visas for life” that enabled the family to travel across the trans-Siberian railway (protected by Swedish safe-conduct papers) and then to Yokohama, Japan. Shrier’s family boarded one of the last ships in Japan with Holocaust refugees heading to the United States.

When the United States denied entry to the Shriers because refugee quotas were exceeded, the family went to Mexico City. His family was able to stay there only because his grandfather served as commercial attaché at the Polish Government-in-Exile’s embassy. Years later, the family obtained permission to enter the United States.

“Their courage and resourcefulness as Holocaust survivors influenced me deeply and helped shape my decision to become an American diplomat,” said Shrier, who is deputy chief of mission at the U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem.

Susan R. Benda, Washington

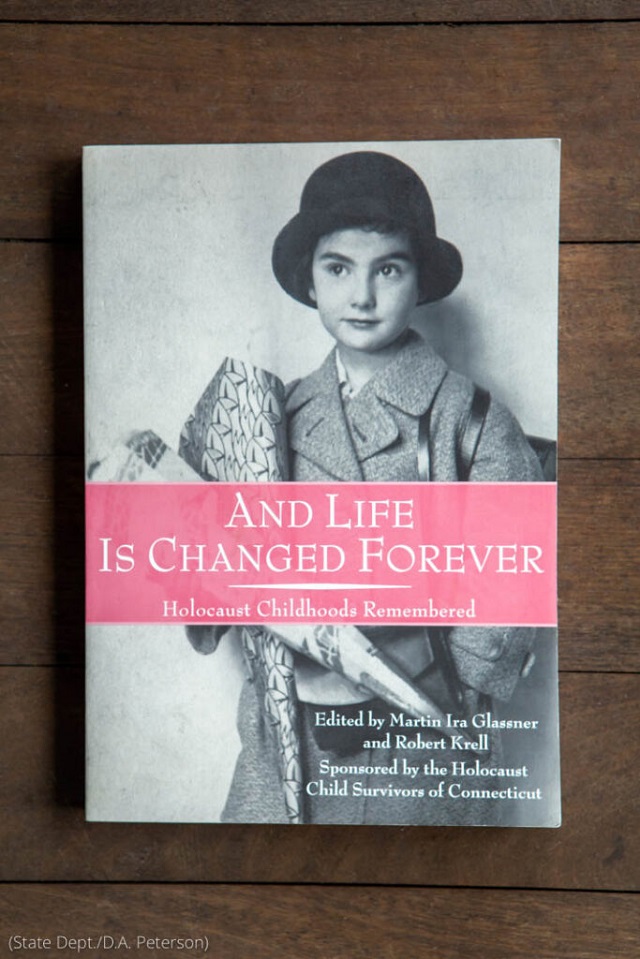

Both of Susan R. Benda’s parents were Holocaust survivors from the former Czechoslovakia. Benda’s mother survived Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. Her father fled to Asia, where he was imprisoned by the Japanese before eventually making his way to the United States. His parents were murdered in the Chelmno extermination camp in Poland.

“When I was young, my parents never talked about their past,” said Benda, who is a lawyer for the State Department. “I knew we were Jewish, that they had accents, and we had no relatives.”

Benda’s mother spoke publicly about her experience as a Holocaust survivor for the first time when she was interviewed in 1979 for a Yale University oral history project. Her father had been a Yale history professor; he died in 1971.

As a State Department employee for more than 20 years, Benda achieved her goal to be an advocate for justice. Her brother also worked at the department. In their roles, she said, they help make their parents’ new country, which they loved, “stand up to the voices of hatred, division and oppression and to fulfill its promise as a beacon of democracy and justice in the world.”

A photo of Susan Benda’s mother, Eva, appears on the cover of a book detailing children’s experiences during the Holocaust. Benda’s chapter is entitled “From Prague to Theresienstadt and Back.” (State Dept./D.A. Peterson)

Banner image: Susan Benda holds a photograph of her parents, Harry and Eva Benda, standing in front of the White House in 1952. (State Dept./D.A. Peterson)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP