During the 1950s, America lived every day in fear of polio. Hysteria was pervasive because there was no cure or prevention.

It would take almost every aspect of American society — parents, children, doctors, celebrities, the media, nonprofits and political leaders — to wipe out naturally occurring polio in the United States. But innovations and lessons learned would allow the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to take the fight around the world.

Polio, short for poliomyelitis, attacks the central nervous system and can lead to permanent disability or death. Infection is most common among infants and children.

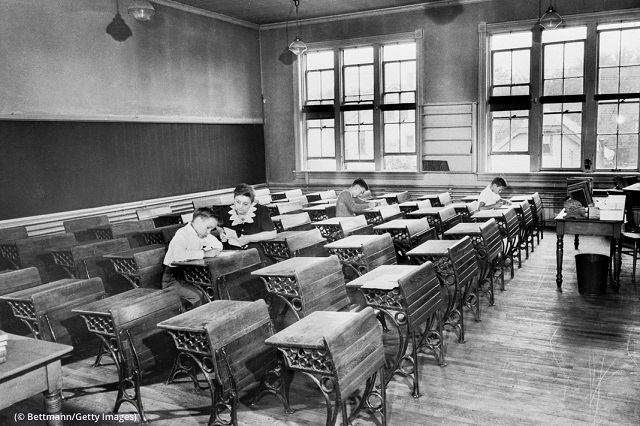

Children’s fears

A sixth-grade classroom in Milwaukee on the first day of school in 1944 is barely occupied because of a polio quarantine. (© Bettmann/Getty Images)

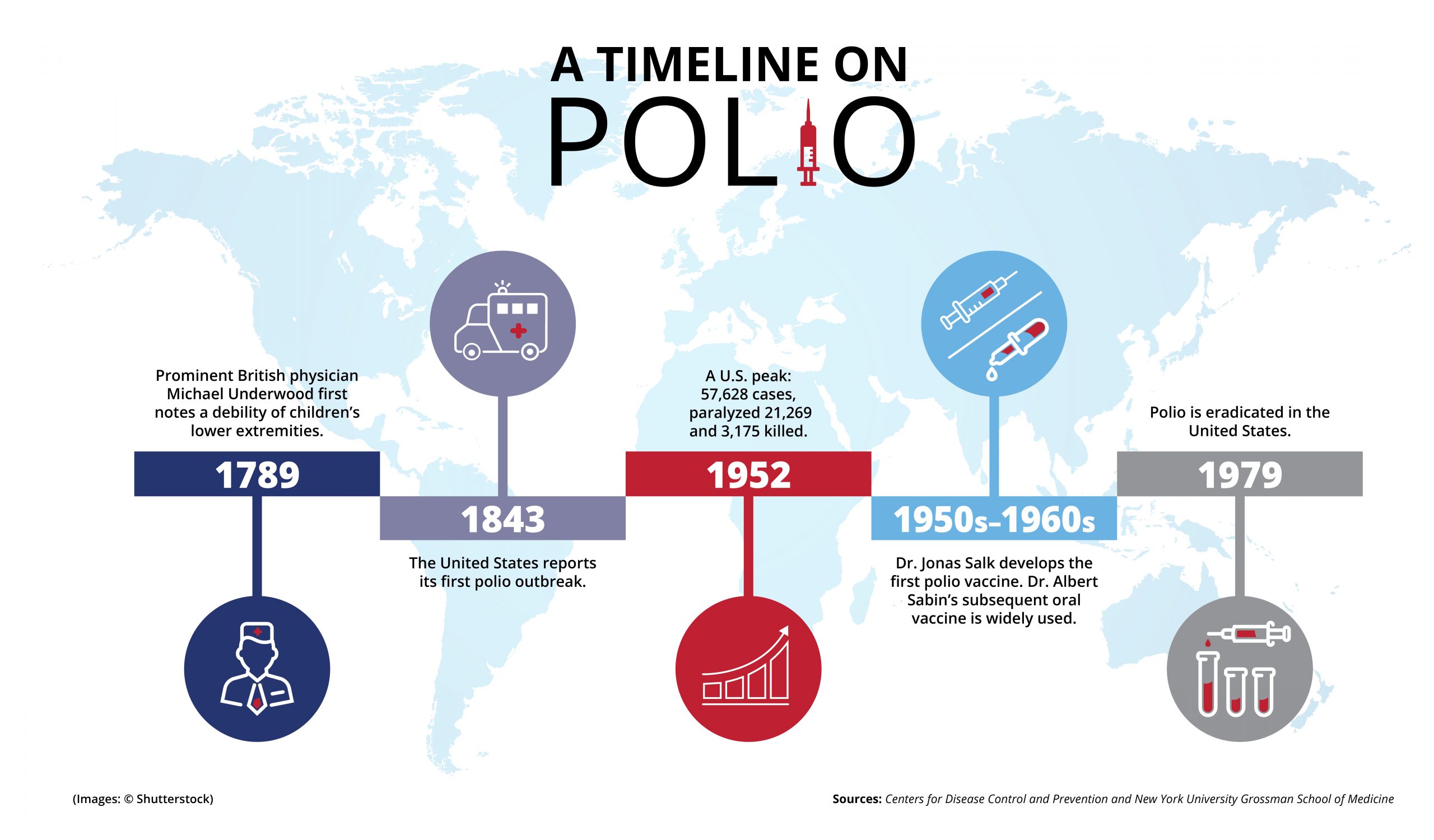

In the 1950s, summer outbreaks of polio touched tens of thousands of children. Polio shuttered beaches and swimming pools, movie houses and baseball fields. Parents urged their children to avoid large crowds. Polio reached its apex in America with a 1952 epidemic that infected 57,628 people, paralyzed 21,269 and killed 3,175.

“I remember going to school as a little boy in New York City, and when you’d come back, you’d see the kid in the wheelchair, the kid in braces, and you’d see the occasional empty desk when you knew the kid wasn’t coming back,” says David M. Oshinsky, author of Polio: An American Story and director of medical humanities at the New York University School of Medicine.

A president takes charge

While polio was rare in young adults and older people, decades before the 1952 epidemic President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had contracted polio. The disease hit him in 1921, at age 39, and left him unable to walk. In 1938, as president, Roosevelt founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (now known as the March of Dimes) to defeat polio.

President and Mrs. Franklin Roosevelt enjoy conversation with young polio patients from the Warm Springs Foundation. (© Bettmann/Getty Images)

An army of volunteers collecting dimes helped the foundation pay for vaccine research, the largest clinical trial in American history and posters that featured afflicted children. Other media campaigns featured celebrities, such as Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe.

For his part, Roosevelt used radio addresses to urge the public to help end polio.

Blazing the path for a vaccine

The talented scientist Isabel Morgan joined the polio researchers at Johns Hopkins University in the 1940s to work on a vaccine. Although she left to raise her family, her contributions and work by the CDC allowed Dr. Jonas Salk of the University of Pittsburgh to create the first polio vaccine in 1954.

To test the vaccine’s effectiveness, volunteers from Roosevelt’s foundation organized a double-blind clinical trial across America that injected roughly 1 million schoolchildren with the vaccine or placebos. The vaccine was licensed for use in the United States on April 12, 1955.

On April 25, 1955, Patsy Murr, a first-grader in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, is vaccinated against polio by Dr. Norman E. Snyder as classmates react. (© AP Images)

Soon after, vaccination campaigns were expanded across the country, identifying critical quality-control measures to ensure safe immunization of children and prompting the CDC to add disease surveillance to its mission.

Sabin Sundays

With funding from Roosevelt’s foundation, Dr. Albert Sabin worked with the CDC to develop an oral polio vaccine in the 1960s that was inexpensive and easy to administer.

American adults of a certain age remember Sabin Sundays, a voluntary immunization program all over the country where millions of children lined up to swallow a sugar cube laced with Sabin’s lifesaving liquid polio vaccine.

All told, these efforts eradicated naturally occurring polio in the United States by 1979.

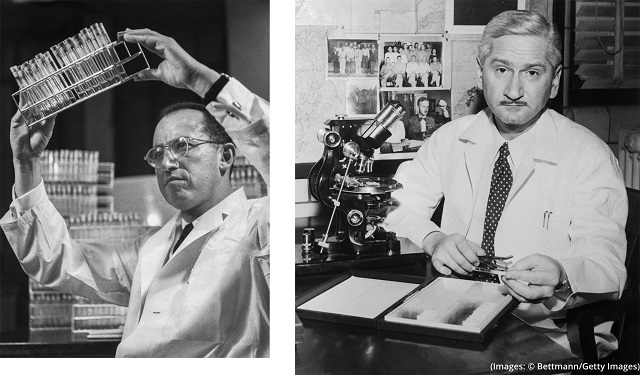

Salk and Sabin are remembered as American heroes because they relieved the “tremendous fear” American parents had. “Polio was an equal opportunity destroyer in terms of infecting and causing paralysis from rich to poor,” says Dr. Stephen Cochi, an immunization specialist at CDC.

Left: Dr. Jonas Salk, who developed the polio vaccine, in his laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh. Right: Dr. Albert Sabin, at work in his laboratory at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, was best known for developing the oral polio vaccine. (© Bettmann/Getty Images)

But the CDC wasn’t finished.

Polio fight goes global

The U.S. helped launch the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 1988 after the World Health Assembly unanimously backed a resolution to eliminate the disease worldwide.

The initiative’s four other partners in the fight are the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Rotary International, UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO). Since the 1990s, the U.S. Congress has appropriated hundreds of millions of dollars for the CDC toward global polio eradication efforts.

A health worker gives a polio vaccination to a student in Peshawar, Pakistan, in April 2019. (© Muhammad Sajjad/AP Images)

As of 2018, there were fewer than 30 reported cases of naturally occurring polio in only two countries — Afghanistan and Pakistan. The goal is getting to zero.

Banner image: In this 1955 photo, Ira Holland, 16, who was stricken by polio when traveling, is readied for an ambulance trip from Boston to a hospital closer to his New York home. (© AP Images)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP