The novel coronavirus pandemic is forcing factories around the world to slow or cease production. This reduced output is disrupting global supply chains that normally keep countries supplied with everything from medicine to garlic to socks.

Part of the problem, economists say, is that today’s supply chains aren’t diversified enough. “There are a lot of choke points where production of certain goods is highly concentrated in one country, sometimes in one city or in one company, and that creates vulnerability,” says Geoffrey Gertz, a fellow in the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution. “We certainly see that with China. The pandemic is really driving home the need to invest more in supply-chain resiliency.”

David Simchi-Levi, a specialist in supply-chain logistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, explains that aggressive cost-cutting strategies years ago are behind some of today’s shortages. “Companies were successful in reducing costs, but they significantly increased exposure to risk,” he said. “And if there is a problem like the one that we have seen in the last [several] weeks, there is a huge disruption to the supply chain.”

A crane prepares to load a container onto the cargo ship Asian Moon at the Port of Miami in 2012. (© Alan Diaz/AP Images)

Simchi-Levi points out that in the 1980s more and more companies moved their activities to Asia, and in particular China. “They were thinking mostly about cost-cutting measures without taking into account, for example, the impact of long lead time, increasing volatility and increasing risk in the supply chain,” he says.

China’s share of trade with the rest of the world has increased dramatically, Simchi-Levi notes. In 2002, during the SARS epidemic, China represented 4.3 percent of the global gross domestic product. Today, China represents 16 percent, he says.

Mapping origins of suppliers’ parts

What’s more, “supply chains overall have gotten more complicated,” Gertz says. “We have more and more companies relying on more and more intermediate suppliers for their production processes.”

David Payne, a staff economist for the business publisher Kiplinger, reports that supply-chain breakdowns go beyond China. “Businesses that import parts or materials from Southeast Asia are finding out that many of those suppliers depend on China for raw materials,” he writes, citing the Cambodian garment factories that were forced to close due to a lack of Chinese fabrics.

Simchi-Levi says companies around the world should invest more in supply-chain mapping. “Not only do they need to understand their suppliers, but they need to understand their suppliers’ suppliers,” he says.

Companies also need to diversify, he says. “Make sure that the supplier has multiple manufacturing facilities in different regions, or that there are multiple suppliers where you can switch from one to another to get the parts that you need. Or you build more inventory than you would typically build.”

Gertz points out that after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, which led to product shortages, there were efforts to build more resiliency into supply chains. But the efforts were short-lived. “There’s always this risk that we’re only cognizant of these vulnerabilities when they’re thrust in our face. [We] are happy to give up resiliency in favor of efficiency in normal times, and then have to be forced to relearn this lesson over and over again,” he says. “The real threat is that we respond to the immediate crisis but don’t put in place any steps to avoid this going forward.”

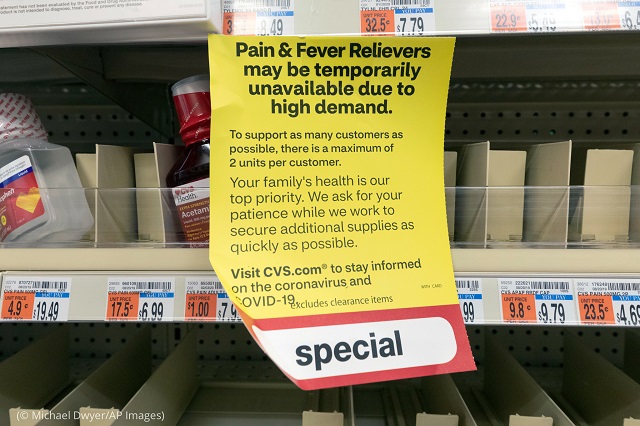

Non-prescription medicines were depleted at this Boston pharmacy on April 3. (© Michael Dwyer/AP Images)

Simchi-Levi thinks this time things will be different. He says recent trade tensions had already motivated companies to rethink their supply chains. “With the pandemic now, it will accelerate the trend,” he says. “When we look at the supply chain 10 years from now, it will have a different structure than the structure we have seen in the last five to 10 years.”

Diversification will be “an essential part of [risk] mitigation,” he says.

Freelance writer Linda Wang wrote this article.

COMMENTS1

おっしゃる通りだと思います。

日本でも、マスクの供給が問題になってます。

それに関連するかもしれませんが、WHOに対するトランプ大統領の見解はとても正しいと思います。

本来、大統領の主張されてることをWHOが率先してやるべきだと思いました。

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP