This year marks the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which granted American women the right to vote. Though the right is taken for granted today, the amendment was a milestone as it legally protected women’s rights and significantly contributed to women’s participation in society. Its impact spread across the world all the way to Japan. But how did the American and Japanese women who shared the same goal of women’s suffrage manage to achieve it?

In the United States, many women began to actively work on social issues after the equal rights movement gathered momentum in the 19th century. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and Susan B. Anthony were among the pioneers who played central roles in fighting for the empowerment of women. In 1848, Stanton and Mott organized a women's rights convention and drafted the Declaration of Sentiments, which was modeled after the Declaration of Independence. While the declaration covered various women’s rights, the one that attracted the most attention was women’s suffrage, as the declaration was the first attempt to demand it. After presenting the declaration, the three women persistently and passionately advocated its principles. Anthony expanded her horizons beyond the United States and established the International Council of Women and the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. As a result, the network of support continued to grow and the passion of the three women was handed down to the next generation after they passed away. Their efforts paved the way toward granting suffrage to American women, and the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified and adopted in 1920.

During the same period of time, on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, a woman who was struggling to improve the status of women became widely known as an educator and welfare worker in Japan. Her name was Kajiko Yajima. Kajiko, who lived to be 92 years old, was still going strong even after she had turned 80. She is renowned for forging ties with Americans and traveled to the United States three times. What is less well known is that she served as a bridge between Japanese and American women and made her presence felt in both countries. So what was her life like?

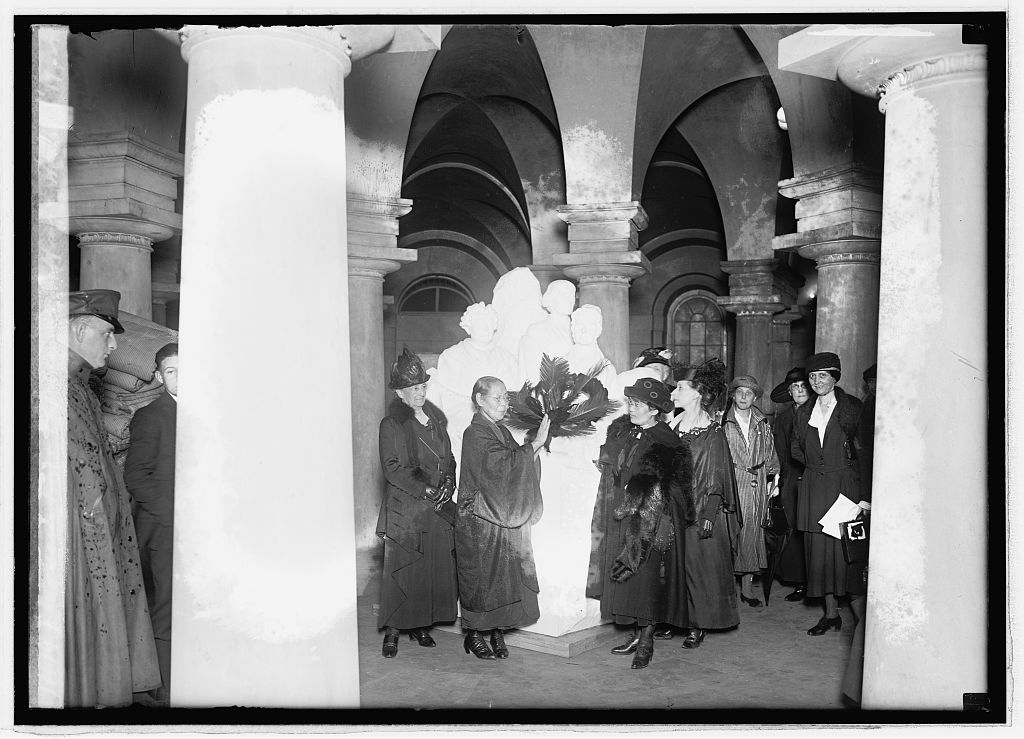

Kajiko Yajima in front of the monument of the three American suffragists during her visit to the United States. November 9, 1921. (Library of Congress)

Kajiko was born Katsuko Yajima, the daughter of a village official in Mashiki Town in Kumamoto Prefecture. At the age of 25, she married Shichiro Hayashi, who was of samurai lineage. But to the surprise of many people around her, she decided to divorce him because of his violent nature and drunken outbursts. She returned to her parents’ home and later went to Tokyo to care for her ailing older brother. During the trip, she noticed a small rudder, called a kaji in Japanese, controlling a big ship and decided to use the notion of a rudder as a compass for her life, changing her name from Katsuko to Kajiko. She was a very strong-willed woman. After her brother recovered, she embarked on a new chapter of her life and began working as a teacher in Tokyo so she could stand on her own two feet. At around the same time, she met someone who would have a significant impact on her later on: Maria True, an American woman from a small town in New York. Maria True traveled to Asia as a missionary and ended up in Japan. She focused on education for women and served as the principal of Shin-ei Girl’s School in Tokyo. She had heard about Kajiko’s fine reputation as a teacher and asked her to teach at her school in 1878. Kajiko was surprised by the offer but accepted it. Kajiko later took another step forward in her career as an educator by becoming the first principal of Joshigakuin, which was established after a merger between schools. But she did not stop there. She wanted to further improve women’s education and dedicated herself to nursing education and childhood education together with Maria True.

Kajiko was also deeply involved in the public welfare services of the Kyofukai Japan Christian Women’s Organization. She was drawn to religion as a result of her daily contact with Maria True and was baptized in 1879. Kajiko took the helm of Kyofukai in Tokyo in 1886 and continued to lead the group after it developed into a nationwide organization through the support of Japanese women. Kyofukai campaigned for women’s suffrage and still engages in activities today to protect the human rights of women and children based on Christian teachings.

Kajiko holding the list of signatures she brought from Japan to the United States. November 7, 1921 (Library of Congress)

Kajiko traveled to the United States in 1906 and 1920 as the Japanese representative of Kyofukai. She made her last visit to the country in 1921 to attend the Washington Naval Conference as a private citizen. Even though she was already 89 years old at the time, she was still passionate about her activities. The fact that a petite woman nearly 90 years old traveled all the way to the United States from Japan amid global uncertainty no doubt touched the hearts of many Americans. Kajiko, who had sought peace and dedicated her life to women, attracted a great deal of attention in the United States and was covered widely by the newspapers there. According to one of the articles, Kajiko delivered the following address at a ceremony held in front of a monument built in honor of suffragists Stanton, Mott, and Anthony: “I am proud to bear this last tribute to the great suffragists who did so much for the women of this nation and the women of all nations. We in our country are just beginning the struggle which you women of America have so triumphantly carried on, and I shall take back to my women the picture of your great pioneers honored in your nation’s Capitol as an inspiration to us in our efforts for our own advancement.”

The Evening Star published a report on Kajiko's visit to the United States. November 10, 1921. Click to enlarge. (Library of Congress)

Kajiko’s proactive attitude was also reflected in her meeting with President Warren Harding. One of the purposes of her trip to the United States was to present to the President a list of signatures she had brought from Japan, which included the names of more than 10,000 Japanese women wishing for peace. In a letter to the President quoting from the Bible, Kajiko wrote: “I am one who prays in hope and faith and gratitude, that you will work for our cause. ‘Forgetting the things which are behind, and stretching forward to the things that are before.’”

Banner image: American sculptor Adelaide Johnson’s “portrait monument” of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott (Architect of the Capitol)

***

Joshigakuin Junior and Senior High School contributed to this article.

Sources:

Kajiko Yajima-den by Ochimi Kubushiro (Ozorasha Shuppan)

Ware yowakereba by Ayako Miura (Shogakukan bunko)

The Library of Congress

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP