A Japanese who can make Americans laugh… in English? Impossible! But there is someone who has succeeded at precisely this feat. Ryosuke Koike, who goes by the stage name Rio, is the only Japanese stand-up comedian in New York City.

A single mic is his only prop. Despite the disadvantage of speaking in a second language, he’s able to make people burst out laughing. As a Japanese on the NYC comedy scene, he is very much the underdog. How did he manage to achieve success in America?

Becoming a comedian in America

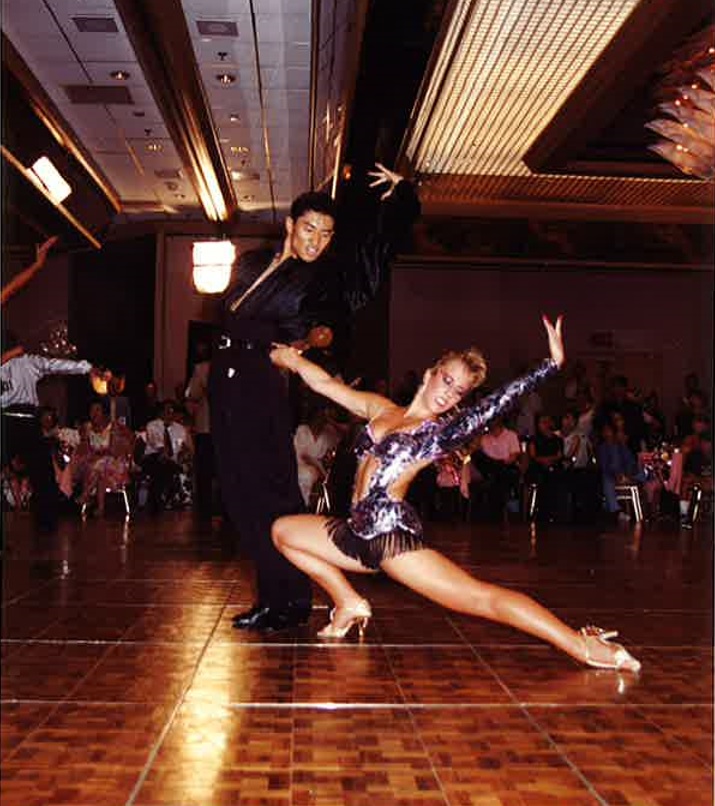

After Rio won a student ballroom dancing championship in Japan, he traveled to the United States because he was fascinated with foreign dancers. But he was forced to give up on achieving that dream at the age of 28 after losing to a pair of dancers who were only 11 years old. He had no choice but to relinquish his goal of becoming a professional in the competitive world of ballroom dancing, and started looking for a class in an entirely different field where he might be able to shine. It was then that he stumbled on a 90-minute comedy class that was offered once a week by the Stand Up NY comedy club.

Competing in the 1994 California Open in Los Angeles

“I was ready to try anything at that point,” said Rio. “If it didn’t work out, I would just drop it, I thought.” Rio joined the class for fun, but it ended up becoming an encounter with destiny.

“I was the only foreigner in the class. I thought there was no way people would think I was funny! As it turned out, though, I was the only one who got laughs! The other students in the class flopped. That made me feel like I was being led into the world of comedy.”

For Rio, the class was a major first step on his road toward becoming a comedian. Many of the Americans in the class quit. The original class of 20 dropped to 10 in just a day. A mere five students remained eight weeks later.

But Rio still had a long journey ahead of him. In an effort to land a gig, he approached the owner of the comedy club without an appointment and spoke with him directly. Even so, it was many years before he would appear live on stage.

RIO performs improv in Manhattan in 2008

“I did cleaning work (at the comedy club) for more than five years,” said Rio. “Some Americans were doing the same kind of thing, but most ended up quitting. They have other options.”

Even after Rio started performing on stage, some of his performances fell flat. He was even booed at times. “If you try too hard to get laughs, you’ll blow it,” and fail, he realized.

“If you don’t take it seriously, though, you’re also going to be a major flop,” says Rio. “I’m Japanese, so it goes without saying that I’m going to experience failure. That’s why I always do tons of preparation while still assuming that I’m going to blow it.”

In search of the American Dream, many people attempt to turn their visions into reality. For that very reason, Rio seems to shine all the more brightly. He focused on practicing every day, working hard, and preparing thoroughly.

Education in Japan and America

By studying in the United States, Rio noticed a major difference between education in Japan and America.

“When the English word ‘education’ was translated into Japanese,” Rio says, “they got it wrong. If the word ‘education’ really means ‘to teach and nurture,’ as the Chinese characters that form the Japanese word for education imply, then I did not receive a bit of education in the United States! In my early days there, I wondered why no one was teaching me anything.”

The comedy class he took didn’t offer any instruction on how to make people laugh. The teacher neither praised nor disparaged the students. The students simply presented their material and decided for themselves whether they wanted to stay in the class or drop out. Rio wanted to learn comedy, but no one would teach him. Then, one day, Rio learned that the English word “educate” comes from a Latin word that means “to draw out.” It was then that Rio realized that he was not being “taught and nurtured” in the art of comedy; rather he was being educated in a way that would “draw out” his talent for comedy. The Japanese concept of education, teaching and nurturing, is very different from the American one, which is about drawing out each person’s unique talents and gifts.

“In Japan, I used to get a grade of 2 in English [on a scale of 1 to 10]. I was not very good at other subjects either. But there was no course in school on how to get laughs in English! In the Japanese education system, students who aren’t good at the nine subjects taught at school simply drop out. American education, though, draws out the talents in such children. America has classes in which people who struggle in the nine school subjects can shine.”

English ability and originality

In university, Rio used to make his teachers sigh out loud because of his inept use of English. Yet, the profession he took up in the end was one that requires a razor sharp command of language – a comedian.

Rio developed his own original method of studying after trying every other method around. He would record spoken English that he didn’t understand and then listen to it over and over again without looking at the spelling of the words. He would say the words out loud at the same time.

English skills are critical to making it in America. But Rio says it doesn’t matter if you’re not good at English.

“The people who succeed in the U.S. are those who have originality. By definition, learning English requires us to imitate Americans. People with a lot of originality are not good at mimicking others, so they tend not to be good at English. You can make it just fine with originality alone.”

RIO on stage at Caroline's Comedy Club, Manhattan in January 2015

Rio says the types of people he thinks should go to the United States are those who are not good at English, those who don’t excel at schoolwork, and those who have no particular talents.

“People today can live to age 100. It may be hard to make a living for all those years doing only what you think you excel at. A skill you never knew you had could open up new vistas for you.”

There are things that are possible in the United States that aren’t possible in Japan. Talents you have yet to discover may blossom in America.

COMMENTS1

[…] […]

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP