When U.S. citizens cast their presidential election ballots, they’ll be voting for someone like Hagner Mister or Rex Teter.

You probably have not heard of Mister or Teter. In fact, most voters who chose them in 2016 did not know who they were. During the last presidential election, Mister and Teter served as electors — a group that is an important part of America’s system for selecting a president. The group is called the Electoral College.

State political parties choose “electors” who convene after Election Day to then choose a president. Voters see the names of the candidates on the ballot, but their votes actually choose the electors who are pledged to those candidates. (Mister, who had been Maryland’s secretary of agriculture, was pledged to vote for Hillary Clinton in 2016. Teter, a Texas preacher, was pledged to vote for Donald Trump that year.)

The Electoral College is difficult to explain, notes Gary Gregg, director of the University of Louisville McConnell Center, a nonpartisan academic center that focuses on civic education. Each U.S. state gets the same number of electors that it has members of the U.S. House of Representatives plus two more because each state has two U.S. senators. Those electors choose the next president.

A system’s beginnings

The country’s founders created a presidency that has executive power to get things done and is representative of the people so it does not become a dictatorship.

A direct popular vote wasn’t a serious consideration, Gregg says, in an era when people were spread throughout the country without today’s communication tools or a developed party system to help them sort through candidates. Elections might frequently have ended with several candidates so close that the House of Representatives would decide the president.

Basing electors on congressional representation mirrors the compromise among states regarding those delegations. States with larger populations are granted a larger, proportionate number of House members, and states with smaller populations are allotted the same number of senators (two) that more populous states have.

The District of Columbia and 48 of the states give all their electoral votes to the candidate who wins their state, whether they squeak by or accumulate thousands more votes. Only Nebraska and Maine allow more than one candidate to win electoral support.

Amel Ahmed, associate professor of political science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, compares the system to the baseball World Series. “The team that wins the series is not the team that gets the most runs. It’s the team that wins the most games,” she says.

Ahmed says the system gives swing states — those that teeter between parties each election year — an outsize influence on the candidates.

But Gregg says the elections of the past 70 years, which have been competitive and have produced many Republican and Democratic presidents, are proof the system works. “The Electoral College has proven to give us good, competitive, valid elections,” Gregg says.

Results

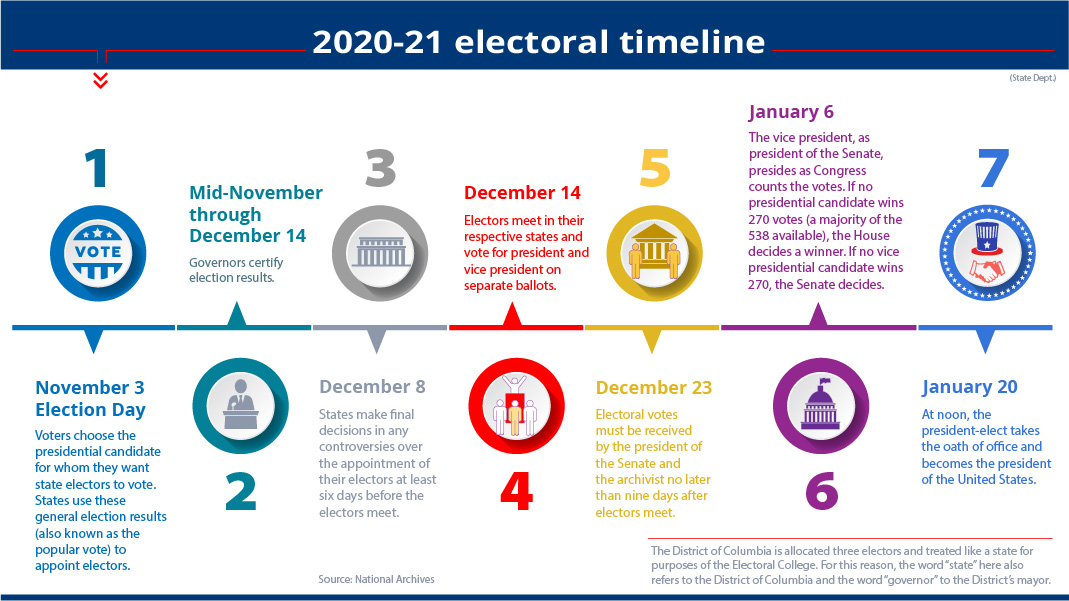

Electors meet in their respective states in December to cast their votes for president and vice president. The results are sent to the president of the Senate, who is the U.S. vice president. The Congress meets in early January to count the votes, after which the president of the Senate declares the winners. On January 20, at noon, the president-elect takes the oath of office and becomes the president of the United States.

COMMENTS2

[…] ・アメリカンビュー:アメリカ大統領選における「選挙人団」を理解する ・BBC NEWS|JAPAN:【米大統領選2020】 どういう仕組みかなるべく簡単に解説 […]

選挙人はどういう形でえらばれるのですか?

例えば、100人の人が投票した。共和党に51票

民主党に49票集まった。 選挙人が3人だとしたら、3人の

A州から3人が12月の投票日に、共和党の候補者に投票する。 以下の☆マークの説明に従い。

☆選挙人は12月にそれぞれの州で大統領と副大統領に投票し、

が、11月3日の投票で、ほぼ全州の選挙人が選ばれる。

その人たちは、共和党、民主党と色分けされ集計される。

ここで、大統領は決まるのに、なぜ12月にそれぞれの州で大統領と副大統領に投票せねばならないのか?

また、勝者総どり方式は、多数決の民主主義の原則から外れていると思うが、なぜこういう方法を取っていて、見直しの議論はないのですか?

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP