The smell of crispy potato pancakes frying in oil is not what most people associate with the winter holidays in the United States. But there I stood in the kitchen, lovingly cooking them one by one in preparation for a holiday brunch I was hosting for my extended family. Along with the potato pancakes, I was serving freshly baked bagels with cream cheese and smoked salmon, pigs in blankets, and hot spiced apple cider. For dessert we had cookies cut into the shapes of Christmas trees and Santa Claus, decorated with red and green sparkly sugar.

The potato pancakes I was making are called “latkes,” a food traditionally eaten on the Jewish holiday Hanukkah, which is celebrated in late November or December. But if this was a Jewish holiday, why were we eating pigs in blankets, little sausages wrapped in puff pastry? Aren’t Jewish people forbidden from eating pork? And why were we having Christmas cookies on a Jewish holiday?

It’s true that many Jews do not eat pork. But my family is far from Orthodox. Although my father is Jewish, my mother comes from a Christian background. When I was growing up, we celebrated a combination of Christmas and Hanukkah traditions, but hardly ever went to church or synagogue. Like my family, the people of the United States make up a patchwork of different cultures and religions, so the winter holiday season, although dominated by Christmas, is punctuated by various festivities.

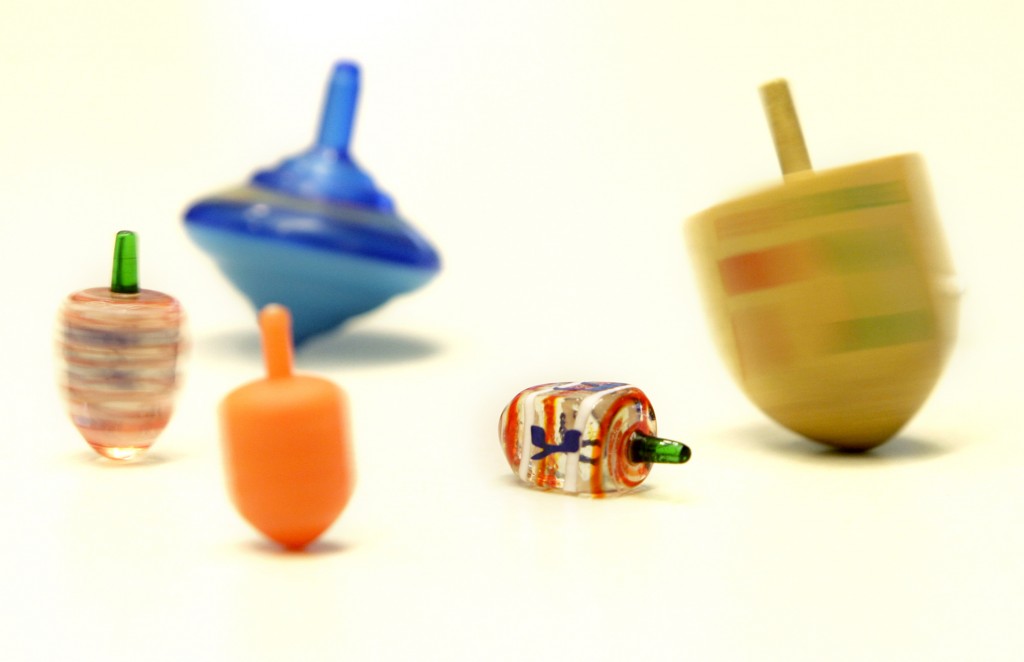

Hanukkah, also known as the “Festival of Lights,” is an eight-day holiday that honors the victory of the Jews in the second century B.C. in reclaiming the holy temple in Jerusalem after the Greek king of Syria outlawed Jewish rituals and ordered the Jews to worship Greek gods. To rededicate the temple, the Jews needed to light its eternal flame, but they only had enough purified oil to keep it burning for one night. Miraculously, the oil lasted for eight days until more could be prepared. Today, Jewish families light candles on a candleholder called a “menorah” for the eight nights of Hanukkah, and eat foods fried in oil to represent the oil that kept the eternal flame burning. Children receive gifts and chocolate coins on each of the eight nights and play with small tops called “dreidels.”

- Potato latkes next to a menorah(AP Photo/Larry Crowe)

- Toy dreidels (AP Photo/Seth Wenig,File)

Christmas is the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ. Although it is actually a religious holiday, many non-Christians in the United States and around the world partake in the secular traditions of Christmas. These include decorating Christmas trees, exchanging gifts, and dressing up as Santa Claus. One of the most universal aspects of the yuletide season is the holiday meal. Christmas culinary traditions vary depending on regional and family customs, but my favorites are oyster stew, a creamy soup made with fresh oysters, and eggnog, a spiced egg-based drink often mixed with rum or brandy, because these are treats that we only get to indulge in at Christmastime.

- Christmas tree cookies (AP Photo/Larry Crowe)

- White chocolate peppermint eggnog, light and airy eggnog, and classic eggnog (AP Photo/Matthew Mead)

But Christmas and Hanukkah aren’t the only holidays Americans celebrate in December. There’s also Kwanzaa, a weeklong celebration from December 26 to January 1 that is based on the ancient harvest festivals held throughout Africa. The holiday was established in the 1960s as a way to help African Americans reconnect with their cultural and historical heritage. Kwanzaa culminates in a banquet of cuisine from various African countries featuring ingredients that Africans brought to the United States, such as sesame seeds, okra, and sweet potatoes.

The Tonel LaKay Drum and Dance ensemble, honoring the cultural heritage of Haiti, performs during the annual Kwanzaaa celebration at the Museum of Natural History on Dec. 26, 2004, in New York. (AP Photo/Jennifer Szymaszek)

Since the U.S. population is largely made up of immigrants and descendants of immigrants from various parts of the world, it’s not surprising that there are many Americans like me who have parents with different religious or cultural backgrounds. Such families sometimes have trouble deciding which events to celebrate during the holiday season. Since my parents were divorced, I would light the candles on the menorah and sing “Hanukkah, Oh Hanukkah” at my father’s house, and then go home to decorate the Christmas tree and sing carols with my mother. Since my parents weren’t particularly religious and wanted us to experience both sides of our cultural heritage, it seemed natural for us to celebrate the holidays in this way.

The tradition of sending Christmas cards is another aspect of the holiday season that has developed to accommodate the wide variety of religious beliefs in America. Nowadays, many individuals and organizations choose to send out generic cards that say “Happy Holidays” or “Seasons Greetings,” instead of “Merry Christmas,” to avoid offending people who don’t celebrate Christmas. On Facebook I’ve even seen people posting holiday messages saying “Merry ChristmaHanaKwanza!” in an effort to encompass everyone on their lists of friends.

Companies also tend to avoid using overtly Christmas-themed designs for their holiday packaging and decorations, sticking to more generic images such as snowflakes and winter scenes. At schools, many teachers plan holiday parties that incorporate aspects of Christmas, Hanukkah, and Kwanzaa so that children can learn to understand and respect the diverse cultures that make up the United States.

Americans celebrate various holidays in December depending on their religious or cultural backgrounds, but all of the festivities culminate on New Year’s Eve. Some adults get dressed up and go out to parties and nightclubs to drink champagne and dance the night away; others indulge in spicy jerk chicken and peanut soup at their Kwanzaa feasts. Many people prefer to huddle on the sofa to drink hot cocoa and watch the “Times Square Ball Drop” on television as midnight approaches. Even young children try to stay up late and count down the last ten seconds until midnight. The next morning on New Year’s Day, the streets are peaceful as most people relax at home, feeling slightly relieved that the hectic holiday season is finally over. Many people also use this new start as an opportunity to make resolutions or goals for the year ahead.

Fireworks erupt from One Times Square as the Waterford Crystal ball that will mark the new year is raised into position at six hours before midnight for New Year's Eve celebrations in New York on Dec. 31, 2013. (AP Photo/Craig Ruttle)

Sascha Udagawa is a writer and editor at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo. She graduated from the University of California, San Diego, with a degree in visual arts. Her interest in Japanese culture brought her to Tokyo in 1991 to teach English, and she worked as a Japanese-to-English translator for a number of years before joining the Embassy.

Sascha Udagawa is a writer and editor at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo. She graduated from the University of California, San Diego, with a degree in visual arts. Her interest in Japanese culture brought her to Tokyo in 1991 to teach English, and she worked as a Japanese-to-English translator for a number of years before joining the Embassy.

COMMENTS1

Very nice description of December holidays and American customs! Well done!

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP