Sixty years ago on August 28, 1963, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a speech that helped propel the passage of the Civil Rights Act less than a year later.

Some of the words King said that day now seem lost to time — tough words about “the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination” are not among the phrases most Americans remember.

It was the words King had not planned that went down in history, placing the speech among America’s most iconic orations.

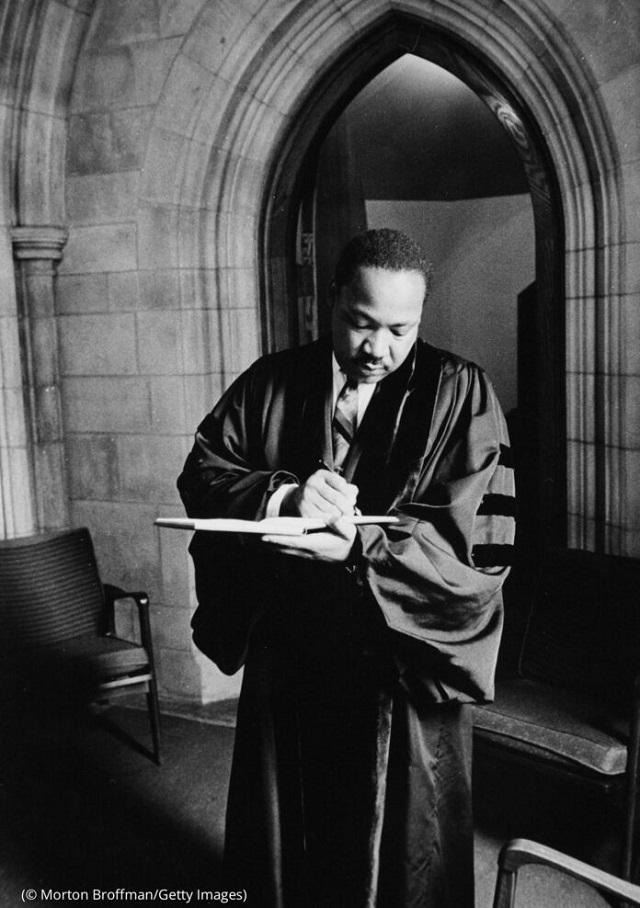

King’s speaking style was influenced by his ministry. Here, on March 31, 1968, King prepares for what would be his last sermon, an appeal to the Washington National Cathedral congregation on behalf of the poor. (© Morton Broffman/Getty Images)

King’s plan at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was to issue a then-radical challenge to the nation. His prepared remarks demanded that Americans make good on the promise of their Constitution and offer equality to Black citizens, says Jonathan Eig, whose biography King: A Life was published this year.

But King — the last of many speakers that day, before 250,000 people jamming the expanse in front of the Lincoln Memorial — decided to blow past his allotted time, even if the audience was tired. He was a Baptist minister and could easily extemporize.

As King stood upon the marble steps, what he decided, Eig says, was to “take the crowd to church.” In adding unplanned passages, he launched into an inspired description of what America could be at its best. Over the elapsing years, Americans have come to refer to his words as the “I Have a Dream” speech.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character,” the civil rights leader said, as one of many repetitions referencing his dream of equality.

King had used a similar “dream” message in two earlier speeches, but this time the crowd was visibly moved and the nation was watching via telecast.

Poet and memoirist E. Ethelbert Miller, a Grammy nominee for his Black Men Are Precious album, says King’s public speaking borrowed techniques like repetition and alliteration from Black spirituals and blues music, which themselves are rooted in African oral storytelling traditions. Like other charismatic Black preachers, King employed “call and response” to rouse the crowd, switching from reading from a text to raising his head and raising the pitch of his voice to connect with his audience.

His repetition of “I have a dream” and “let freedom ring” makes his poetry easy to remember, Miller says.

The speech became one of the most famous orations of the 20th century and a cornerstone of American culture. And while King expressed some sentiments without preparation, he chose his words carefully. “’I have a dream’ connects to the American dream, which is foundational to this country,” Eig says. “He’s calling on patriotism. He’s calling on religious faith. He’s calling on our best instincts.”

King leans forward and smiles at Mahalia Jackson as she sings at the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. (© Bob Parent/Getty Images)

King also drew on poet Langston Hughes’ idea of a dream deferred, says Miller.

Some people credit singer Mahalia Jackson, who shared the packed stage with King, for encouraging him to “talk about the dream.” (She may have heard him refer to his dream before.) But Eig sets the record straight. While Jackson did call out, King had already begun improvising.

It was the first time many white Americans had heard the power of a Black preacher. When King visited President John F. Kennedy in the White House afterward, the president was clearly moved and repeated the phrase “I have a dream” back to King.

“It resonated for a lot of people because it was the first time anybody had seen that sort of scene on television — Black and white people holding hands,” Eig says. “On top of that beautiful image, King’s speech really offered a vision for what America could be.”

President John F. Kennedy smiles at leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom at the White House August 28, 1963. From left: King, John Lewis, Rabbi Joachim Prinz, the Reverend Eugene Carson Blake, A. Philip Randolph, Kennedy, Walter Reuther and Roy Wilkins. Behind Reuther is Vice President Lyndon Johnson. (© Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Today, the speech is taught to schoolchildren as an inspiring blueprint of living without prejudice, Eig points out. The closing — which hails the freedom that democracy promises and refers to some of America’s diverse race and faith groups — is often quoted.

When we allow freedom ring,

when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet,

from every state and every city,

we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children,

Black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics,

will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

Free at last! Free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last.

Sixty years on, Miller notes, King’s birthday is a national holiday and “he is as important as America’s founding fathers.”

Banner image: Martin Luther King Jr. waves to supporters August 28, 1963, on the National Mall in Washington during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where King delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech, which mobilized supporters of desegregation and prompted the Civil Rights Act of 1964. (© AFP/Getty Images)

The original article is here on ShareAmerica.

COMMENTS1

“My Thoughts on Dr. King”

I wanted to share my thoughts about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who was a really important person in history. Even though I’m just 10 years old, I’ve learned a lot about him in school, and I think he did some amazing things.

Dr. King believed in treating everyone fairly, no matter the color of their skin. That’s called “equality,” and it’s something I believe in too. He wanted people to be kind to each other and not use violence to solve problems. I think that’s a great idea.

One thing I really like about Dr. King is his dream. He dreamed that one day, kids like me could play and go to school with kids from all different backgrounds, and no one would be treated differently because of how they look. That’s a dream I have too.

Even though Dr. King’s time was a long time ago, his message still matters today. We should be nice to each other, help each other, and stand up for what’s right, just like he did. He showed us that even if you’re young or small, you can make a big difference.

So, on his special day, I wanted to say that I look up to Dr. King, and I want to keep his dream alive by being a good and fair friend to everyone I meet.

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP