When I close my eyes, I can picture the brilliant blue sky over Iowa City and the familiar faces of my friends from the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program (IWP). I was fortunate enough to be invited to the IWP in the fall of 2019 as the first female poet from Japan to participate in about 20 years.

Those three months in Iowa were like a dream. The IWP 2019 cohort consisted of 28 writers, including poets, novelists, critics, playwrights, and scriptwriters, who represented 25 countries and one region: Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, China, Indonesia, Myanmar, Singapore, Nepal, and Japan in Asia; Turkey, Israel, Morocco, Zimbabwe, Algeria, Malawi, Nigeria, Eritrea, Namibia, and South Africa in the Middle East and Africa; the Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, and Greece in Europe; and Mexico and Argentina in North and South America. The IWP’s robust intellectual foundation comes from its stance of treating and supporting all ethnicities and literary genres equally, regardless of conventional hierarchies. Ours is a time in which we can no longer predict how literature will be defined and what will determine its value. The IWP recognizes the complexity of our times and attempts to envision the “future” of literature as clearly as possible.

As part of the program, the IWP writers held events such as readings, lectures, and panel discussions, where they not only presented their own works but also led discussions. All of us enjoyed participating in vibrant exchanges as if we were students again. In addition to students from the University of Iowa, many literature enthusiasts from the community attended the events. Iowa City was designated a UNESCO City of Literature in 2008 and there is a deep-rooted love for the art form there.

Delivering lectures and participating in panel discussions in English presented a major challenge for me. I must confess that I was shocked and on the verge of despair when I saw the other IWP writers delivering their unique presentations interspersed with humor and wittily responding to questions from the audience. Motivated by a desire to improve my English as much as I possibly could, I frequented local pubs as often as my stamina allowed to take part in lively discussions.

Perhaps the essence of what I gained through my experience in the IWP was the capacity to explain my work in a way that transcends borders. In addition to being able to speak a foreign language, I needed to convey the message behind a particular work and the underlying philosophy and catalyst that made me want to create it. The University of Iowa students and city residents had no prior knowledge of my poetry or background. Standing before them, I wondered what kind of message I should convey.

We were asked to read our own works aloud and explain the perspectives behind them. I guess that’s why author readings are so popular across the United States. Learning about the author’s perspective piques people's interest, which in turn boosts book sales and can lead to critical reviews.

Fortunately, thanks to the superb editing of Jeffrey Angles, I was able to publish an English translation of my anthology of poems titled Factory Girls while I was in Iowa. The publisher, Action Books, is famous for publishing avant-garde poems translated from other languages. During the program, in addition to reading my poetry to the audience at the readings, I would explain that I was born into a family that ran a textile factory in the rural Japanese city of Kiryu, Gunma Prefecture. I explained that while telling the story of the rise and fall of the textile industry in illusionistic epic narrative poems, I strived to go beyond “standard” Japanese and incorporate local words and rhythm into my work to create a new language of poetry. It is my belief that language is not a national or local characteristic, but an individual one.

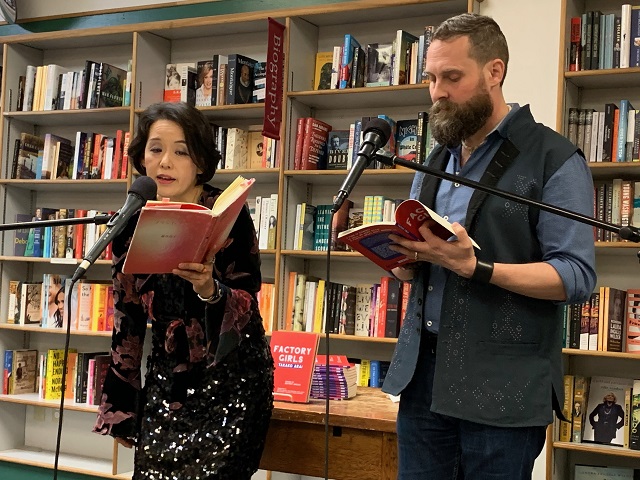

Poetry reading with Jeffrey Angles at an IWP open house event at a local bookstore.

Another memorable occasion during my time there was when the rough cut of the film Songs Still Sung: Voices from the Tsunami Shores, which I had been working on with director Yoi Suzuki, was finalized and shown to the audience at an IWP event. The film is a documentary about an elderly woman (Onba) who lives in Ofunato in Iwate Prefecture. I met her while working on my book, Poems of Ishikawa Takuboku in the Voices of Tohoku Grandmas. The film’s subtitles were made by the students in a seminar on Japanese literature translation and their instructor, Kendall Heitzman, an associate professor of the university. Thanks to the almost 100 people who came to see the film’s screen debut, the event was a great success.

More than anything, I was blessed to have the opportunity to get to know my fellow participants of IWP 2019. I cherish the memory of every moment we spent together. We became fast friends, treating each other like family. To this day, we often check on each other via WhatsApp and other social media platforms.

Takako Arai with her fellow IWP 2019 writers.

Upon returning to Japan, I contacted IWP Director Christopher Merrill to let him know I had arrived safely. In his reply, he thanked me for building a strong bridge over the Pacific. I hope that other Japanese writers will take up the baton and participate in IWPs in the future. In closing, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to the IWP’s greatest supporter, the U.S. government, which also sponsored my participation in the program.

***

When the Moon Rises (from Soul Dance)

By Takako Arai

Translated by Jeffrey Angles

It is the night shift in an abandoned spinning factory

There is only a single light bulb here

The spools of thread turn by themselves

Click goes the bobbins

Changed by the machines

It has already been a decade

Since this place shut down

But when the moon rises, it begins to work

Its strange automation

They say soon after the war

A factory worker’s hair got tangled

In the machines, killing her

There are things that float here

But this is not the work of ghosts

No

In the factory

There are peculiar habits

That is what I mean

Peculiar habits remain here

An old lady who spun thread

For forty-four years here

Still licks her index finger and twists

Even on her deathbed

She cannot escape that gesture

That must be true in the netherworld too

Since threads are so infinitely thin

The gestures sink into the bodies

Of those who manipulate the machines

They possess them

Look

How the raw silk thread

Is pulled smoothly

From the factory woman’s fingers

Then dances endlessly

The factory is that way too

The axle of the spinning wheel

Remembers

The molecules of steel

Hang their heads in the

Direction in which they spin

Then get caught up

Clanging emptily

When the moonlight pours in

It is not just the tide that is full

Emptily

Emptily

The spinning wheels spin

The threads swim

Through the abandoned factory

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP