In the wake of the new coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. Department of Defense has given $1.1 million in laboratory and diagnostic supplies to dozens of partner nations in Africa, Asia, Europe and South America.

The U.S. military’s health labs have spent $6.9 million on biosurveillance of the virus that causes COVID-19, conducting studies in 30 countries to contain the disease and maintain military readiness. Meanwhile, department scientists are working to develop a COVID-19 vaccine to protect people around the world from the disease.

These efforts to slow the novel coronavirus as well as to treat or stop the disease it causes are the latest in a long history of military assistance in similar health crises.

In the 1990s, when Dr. Nelson Michael drove through Uganda as HIV spread there, he saw a country so dominated by death that street vendors sold coffins on the roadside.

But years later — after the Department of Defense helped roll out the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, commonly known as PEPFAR — Michael, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, returned to Uganda. This time, when he drove from Entebbe International Airport to Kampala, he saw roadsides filled with people hawking furniture, not coffins.

“We made a big impact,” says Michael, a retired colonel who helped create vaccines for Ebola and Zika and is now working on vaccines to protect against HIV and COVID-19. “People are alive today. And they’re thriving. And, definitely, these societies are safer.”

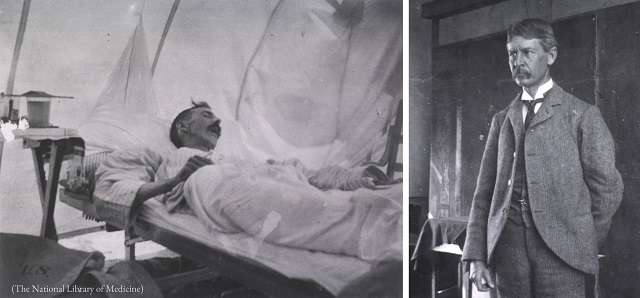

Left: A yellow fever patient in a Cuban hospital in 1898. Right: Major Walter Reed, a U.S. Army surgeon, led a military commission that helped reduce yellow fever in Cuba and Panama. (The National Library of Medicine)

The U.S. military has a long history of helping control pandemics, and for good reason. During America’s first 145 years, more of its military personnel died from infectious disease than from enemy combat, according to a 2008 study. Medical advancements in vaccines and antibiotics helped reverse that trend during the World War II era.

Today, outbreaks threaten not only service members, but also American civilians and allies. The U.S. military’s scientific, medical and public health communities research epidemic diseases around the world to treat patients suffering from them and to eradicate them.

Here is how the military has helped fight select global pandemics.

Ebola

In 2014, more than 2,800 members of the U.S. military deployed to Liberia to stop the epidemic and help infected people.

Troops trained 1,539 local health care workers, established a 30-person support team of civilian medical professionals, constructed 10 Ebola treatment units, assembled seven mobile labs, processed more than 4,500 samples and provided 1.4 million sets of personal protective equipment to local health workers.

In 2014, the U.S. Air Force’s Kasey Unterseher helps a Liberian health worker suit up to enter an Ebola treatment area. (U.S. Army/Staff Sergeant V. Michelle Woods)

Moreover, the U.S. Army Military Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency developed vaccines and treatments to combat Ebola and save lives. In total, the U.S. Department of Defense spent $400 million on Ebola-related operations.

“People were very shocked that some of the first people that went to Africa to help with that were military folks,” says Steven P. Bucci, who spent three decades as an Army Special Forces officer and Pentagon official and is now a Heritage Foundation fellow.

But they are well trained for such work.

H1N1

During the initial stages of the 2009 H1N1 influenza virus (or swine flu) pandemic, U.S.-funded military medical diagnostic facilities were instrumental in detecting cases in the Middle East, Africa and East Asia.

The Department of Defense trained first responders and gave them medical supplies.

The U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit Number 3 in Cairo trained scientists and technical experts from 32 countries (in Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia) in laboratory techniques and diagnostic methods.

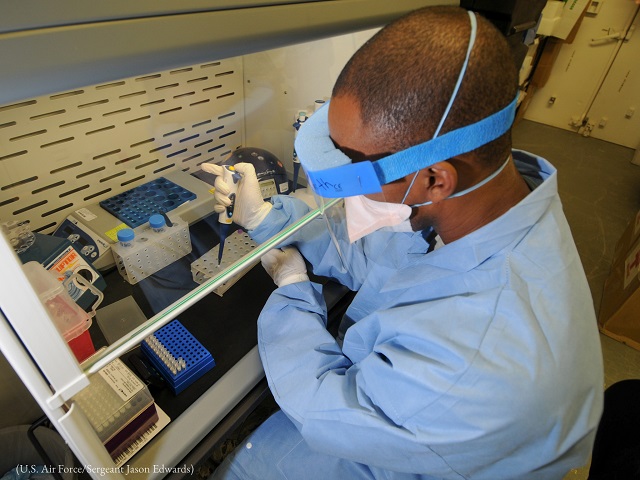

Vernon Smith of the U.S. Air Force extracts ribonucleic acid from a swab sample for H1N1 screening in 2009. (U.S. Air Force/Sergeant Jason Edwards)

Early recognition of the illness’s severity, a quick response by government agencies worldwide, and the knowledge that H1N1 shared a similar genetic makeup to known flu viruses helped experts develop an effective test kit by late April 2009 and release a vaccine in October 2009.

SARS

Widespread attention to the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) triggered an international scientific effort in 2003, leading to discoveries that limited the outbreak. Researchers with the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, Maryland, tested hundreds of existing drugs to determine their efficacy in fighting SARS and collaborated with research centers developing new drugs. The lab discovered that the drug interferon could block the SARS virus, a discovery that set the stage for further research on interferon.

Meanwhile, the U.S. military worked to halt the spread of the virus among troops stationed in South Korea. The U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) command surgeon assembled a team to develop measures to keep service members safe and reduce the spread of SARS. USFK leadership communicated with the South Korean media and provided a hotline to answer questions South Koreans had about the virus.

Just a small number of SARS cases have been reported since the 2002–2003 outbreak, according to the World Health Organization.

HIV/AIDS

Left: Samantha Greeninger, an Army Reserve medic, holds a Ugandan girl’s hand as they wait for HIV test results — the girl tested negative. Right: Greeninger and a Ugandan medic entertain children awaiting treatment at the Pajimo Clinic. (U.S. Army/Major Corey Schultz)

The U.S. Military HIV Research Program (MHRP), formed in 1986, has partnered with research centers in Asia, Africa and Europe to conduct research, testing and clinical trials and to educate.

In January 2004, a group of scientists led by MHRP’s Ambassador Deborah Birx (now the White House coronavirus response coordinator) and including researchers from the Royal Thai Army and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research vaccinated 16,000 people in a clinical trial.

The researchers discovered that a combination of two vaccines could lower the rate of infection of a form of HIV found in Thailand by approximately 30 percent. It demonstrated the viability of a potential vaccine to prevent HIV. MHRP’s vaccine trials continue in Thailand and parts of Africa.

Beyond that, the U.S. military is on the front line of HIV prevention and treatment around the world. The Department of Defense HIV/AIDS Prevention Program, as one of PEPFAR’s key implementers, helps foreign military partners develop and implement culturally appropriate, military-specific HIV/AIDS prevention, care and treatment in 53 countries. This means testing soldiers and their families for HIV, providing lifesaving antiretroviral treatment services in mobile units and supporting safe sex education.

Banner image: Misook Choe, with the Emerging Infectious Disease Branch at the Walter Reed Army Institute, runs a test while researching COVID-19. (U.S. Marine Corps/Staff Sergeant Michael Walters)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP