In March 1879, the Kingdom of the Ryukus, which had lasted for more than 450 years, came to an end. Annexed by Japan’s Meiji government, the kingdom became Okinawa Prefecture. Shuri Castle was surrendered, and King Sho Tai was moved to Tokyo. Around that same time, much of the artwork, antiquities, and documents belonging to the royal family were taken to Tokyo, as well. These heirlooms were long stored safely in the Sho residence in Tokyo. Recently, though, they were donated to Naha City, and they are at present on display in the Naha City Museum of History.

The antiquities that were left behind in Okinawa, meanwhile, were stored in Nakagusuku Palace, the residence of the Sho clan that lay across from Shuri Castle. In the midst of the heated fighting in the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, eight employees of Nakagusuku Palace hid a number of valuable heirlooms of the royal family in a gutter on the palace grounds before fleeing; the antiquities included crowns and the “Omorosaushi,” a collection of Ryukyuan folk songs that date back centuries. When the workers returned after the war had ended, they found that Nakagusuku Palace had burned to the ground and that all the valuables they had hidden had been carried off.

The “Omorosaushi” was discovered in the United States a few years later, and it was returned to Okinawa under the name of the President of the United States in 1953 on the occasion marking the 100th anniversary of the first arrival in Japan of Commodore Matthew Perry. The “Omorosaushi” was discovered when the former U.S. serviceman who is believed to have removed it – Carl Stanfelt – asked a Harvard University professor to appraise it. The whereabouts of dozens of other pieces, however – including crowns, royal portraits, and lacquerware – remain unknown. Portraits of the Ryukyu kings now hang in the since-restored Shuri Castle, but these are black-and-white photographs taken before the war. They will remain there until the colorful original royal portraits are found.

Clinton’s Visit to Okinawa

When Okinawa hosted the G-8 Summit in 2000, then President Clinton visited the island prefecture to attend. The U.S. Consulate General in Naha proposed to the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo and the Department of State that being able to return even one missing artifact to Okinawa – if one could be found – would greatly please residents there. Unfortunately, no piece could be located in time, but the proposal did lead to the Department of State the following year inviting three experts to take part in the Department-sponsored International Visitor Program for the purpose of investigating displaced cultural properties. With the prompt dispatch to the United States of an official from Okinawa Prefecture, 11 artifacts – crowns, portraits, and hibenfuku (ceremonial vestments worn by Ryukyuan kings) – were registered on the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Stolen Art File. Recovering stolen art is not an easy task, but the residents of Okinawa were pleased to hear that a step toward that end had been accomplished.

An Image of War Trophies

When I told people around me that I wanted to visit the United States to investigate the fate of Okinawan antiquities, every single one of them replied that as America had taken lots of “war trophies,” they hoped I would be able to get some of them returned. Many Okinawa residents are under the impression that Okinawan artifacts currently in the United States were all removed by U.S. military personnel after the Battle of Okinawa, a view that has been reinforced by any number of newspaper articles taking up the return of such war trophies in the past. Such items returned this way included valuable cultural assets like the bells from Gokokuji Temple and Daisho Zenji Temple. More recent returned items include personal effects like photo albums and letters. In addition, writers like Donald Keene, who was in Okinawa during the war, have written about the American frenzy to collect war booty during that time. Given the history, as well as the fact that many of the items taken from Nakagusuku Palace remain unaccounted for, it is not difficult to understand how this sort of image took root. But how accurate is it?

The report compiled by Okinawa Prefecture

Okinawa Prefecture’s Investigation

Beginning in 1990 and continuing over a period of five years, officials from Okinawa Prefecture visited the United States and catalogued 1,041 Okinawan artifacts stored at 34 U.S. institutions. The report they produced contained the first reference to the fact that there were 197 Okinawan artifacts stored at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. Wanting to know more, I immediately called the curator the prefecture had sent. I asked how so many Okinawan artifacts had ended up in this Puritan town known mainly for its witch hunts in a distant era. The curator told me that while the prefecture investigated where such artifacts were located, it did not look into how they had gotten there. He suggested that since I speak English, I could pursue that line of inquiry myself. Okinawa Prefecture had not investigated the provenance of the artifacts – that is when, by whom, and why they were taken to the United States. I had great interest in this story’s background, but I did not know how to go about pursuing it. I decided to undertake specialized research as the theme of my thesis as I went for my master’s degree under Professor Kurayoshi Takara at the University of the Ryukyus.

Gap Between Image and Reality

Based on the report prepared by Okinawa Prefecture, I gathered information by visiting 15 major art and history museums in the United States, and by getting replies by email or post from 22 other museums that I was unable to visit. As a result, I was able to determine that there were a total of 1,984 Okinawan artifacts stored in 37 institutions, and I could confirm the provenance of most of them. Looking at the 1,984 artifacts by category, there were 569 ceramics, 501 written documents, 420 dyed fabrics, 289 pieces of lacquerware, 10 paintings, and 194 other pieces, including old coins. Examining when these artifacts were acquired by the U.S. institutions, around 400 were obtained in the prewar years and during World War II, some 1,200 were obtained between 1945 and the reversion of Okinawa to Japanese rule in 1972, and roughly 400 more were obtained after reversion.

The results of my research clearly demonstrate that the tendency of Okinawa residents to associate Okinawan artifacts in the United States with war booty is unfounded. On the contrary, the majority of these artifacts were purchased in the prewar and postwar periods in both Okinawa and mainland Japan by individual collectors and museums that had an interest in Okinawan history and civilization and recognized the value of such artifacts. They were collected from the standpoint of scholarship or as works of art. There were, to be sure, several pieces that were clearly taken as the spoils of war. For the most part, however, war trophies taken by U.S. military personnel are not displayed at public institutions but have been relegated to the backs of shelves in these soldiers’ homes, where they have been left to gather dust.

Including private collections, some 37 institutions in the United States have Okinawa collections, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Honolulu Museum. Each of these collections has its own heart-warming story regarding how the artifacts ended up on the other side of the world. In this article, I would like to focus on the movement of such artifacts to the United States prior to World War II.

Interest Among Harvard Scholars

In the course of my research, I learned that a number of scholars who had graduated from Harvard University collected nearly 400 Okinawan artifacts from Okinawa and mainland Japan around the time of the dissolution of the Kingdom of the Ryukyus in 1879. They had been influenced by Edward S. Morse, who had discovered the Omori shell mound, an archaeological site dating back to the Jomon period (14,000 BCE – 400 BCE). These scholars trained by Morse collected Okinawan artifacts into the early twentieth century, and these collections are now displayed in such places as the Peabody Essex Museum (252 pieces), the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (35 pieces), the Arthur M. Sackler Museum at Harvard University (10 pieces), the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (57 pieces), and the Smithsonian (25 pieces).

Morse’s Okinawa Collection Network

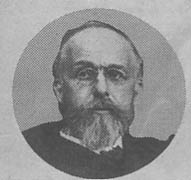

Edward Morse

Edward Morse was a zoologist who studied at Harvard, and he came to Japan in June 1877 for the purpose of studying the brachiopod known as lingula anatina. In September of that year he was employed by Tokyo Imperial University as a professor of zoology. With his discovery of the Omori shells, he was one of the first to introduce Darwin’s theory of evolution to Japan’s educated class.

Morse visited Japan three times between 1877 and 1883, gathering the estimated 5,000 pieces of Japanese ceramics and lacquerware currently displayed at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. He also collected an estimated 30,000 folk tools from the Meiji era (1868-1912) and donated them to the Peabody Essex Museum, of which he was the curator. Among the 30,000 pieces were 12 from Okinawa. As there is no record of Morse ever having visited Okinawa, he likely obtained them in mainland Japan.

After returning from Japan, Morse delivered passionate lectures about the country in Boston, exerting a profound impact on area intellectuals. Well-to-do graduates of Harvard found his enthusiasm for Japan infectious, and they threw themselves into studying and collecting Japanese art. Not only did these students eventually demonstrate deep knowledge of Japanese and Eastern art, many of them used art to create bridges between Japan and the United States. I would like to introduce some of the people in Morse’s network who became collectors of Okinawan artifacts.

Dr. William S. Bigelow (Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Ryukyuan lacquerware)

Dr. William S. Bigelow

William Bigelow was born to a wealthy family in Boston, and he graduated from Harvard University in 1874. Bigelow invited Morse to his villa, where they stayed for a month. Afterward, he accompanied Morse to Japan. During his ensuing seven years in Japan, Bigelow collected some 40,000 pieces of Japanese art, which he donated to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Because of this gift, the Boston Museum now has the largest collection of Japanese art anywhere in the world outside of Japan. Morse and Bigelow, together with Tenshin Okakura and Ernest Fenollosa, traveled far and wide across Japan to collect folk artifacts. At the introduction of Morse, Fenollosa arrived in Japan in 1878 to serve as an instructor at Tokyo Imperial University. He became known as a benefactor of Japanese art.

Bigelow obtained 36 pieces of Ryukyuan lacquerware during his stay in Japan, which he donated to the Boston Museum in 1911. It is believed that these pieces had made their way into the marketplace in mainland Japan after the invasion of Ryukyu by the Satsuma Domain in 1609. In the course of my investigation, I photographed eight lacquer pieces in the Bigelow collection, and several of them bore the royal seal.

Dr. Seiichi Tejima, (Peabody Essex Museum, Ryukyuan artifacts)

Seiichi Tejima

During his time as an instructor at Tokyo Imperial University, Morse met a great many leading Japanese intellectuals, including Yukichi Fukuzawa. Another such person was Seiichi Tejima. Morse had been systematically collecting nearly every kind of folk tool used in the Meiji era, but his collection was inadequate with regard to certain items. In particular, he had only 12 Ryukyuan artifacts. He asked Tejima to gather some.

There remains a letter Tejima wrote to Morse dated September 30, 1886. In it, he had written: “I am pleased to say that although it took some time, I am able to give to your museum the pieces that had been promised on the attached list.” In addition to everyday Japanese goods, the attached list included mention of “everyday things used by the people of Ryukyu,” some 36 Okinawan artifacts.

Japan’s Ministry of Education in 1887 donated to the Smithsonian several dozen Japanese artifacts, of which 25 were Okinawan. This was done in accordance with an agreement between Japanese Ambassador to the U.S. Ryuichi Kuki and the Smithsonian, but it is believed that it was spurred by the artifacts sent from Tejima, who was the curator of the Tokyo Educational Museum, to Morse a year earlier. At the time, the Peabody and the Smithsonian had an arrangement through which they shared with each other the artifacts brought back from the Ryukyu Kingdom by Admiral Perry.

Dr. Landon Warner (Peabody-Essex Museum)

Landon Warner worked at the Boston Museum as an assistant to Tenshin Okakura, and in 1907 he was sent to Japan as a trainee for the museum. Just prior to his return, he traveled to Okinawa to collect folk artifacts.

A woman working on an old loom

According to Warner’s diary, he departed Kobe on November 2, 1909, and arrived at Naha, Okinawa, on November 7. In his entry for November 9, he wrote: “While I intend to collect folk artifacts for Harvard’s Peabody Museum, if the museum is unable to purchase such items, I plan to give Morse a chance to get them for the Peabody Museum in Salem.”

Warner set out for Shuri, and he took his time along the way to do as much collecting as possible. He even had women brought in from other villages to demonstrate how to weave on a type of loom that had already fallen into general disuse by that time. Warner was impressed by Japanese folk artifacts, and he invited Souetsu Yanagi to come to Harvard University as an art instructor. Warner was also apparently keenly aware of the meaning of collecting such artifacts.

Whether due to budgetary constraints or other considerations, Harvard’s museum was in the end unable to purchase the items that Warner had collected. Warner later wrote a letter to Morse outlining the Okinawan artifacts he had obtained. Morse’s museum, unfortunately, did not have the funds to purchase the items. Warner, however, did not have the leeway to do as Morse did and simply donate the artifacts he had collected.

Charles Weld

The 134 folk artifacts that Warner had collected in Okinawa were eventually purchased by the wealthiest man in Boston, Charles Weld, who donated them to Morse’s Peabody-Essex Museum. Warner held on to the Okinawan dyed fabrics that he loved so much and left them to his daughter, who later donated these 10 pieces to the Sackler Museum at Harvard.

Weld’s grandfather had made a vast fortune through trade using the commercial shipping fleet he created, which stretched from the North Atlantic to the West Indies. Like his grandfather, Weld also loved the sea, and he was fascinated by different cultures and civilizations. A Harvard man himself, Weld had great affection for the younger Morse, and he donated artifacts from various countries to the Peabody Museum, which Morse headed, in order to aid Morse’s research.

The Warner legend

For his efforts to facilitate the spread of Japanese art, Warner was presented by Emperor Showa with the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Second Class. Warner was an accomplished writer, addressing such esoteric topics as Japanese sculpture in the Suiko era (593-628 CE) and Japanese art aesthetics. During the Occupation after WWII, he served as a technical adviser to Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Japan Douglass MacArthur on art and important monuments.

During WWII, Warner is believed to have protected the cultural assets of Japan’s former capitals Kyoto and Nara by lobbying the U.S. government not to bomb them. To honor this record, monuments to Warner were erected in five different locations, including Kamakura and Nara. A memorial to him was created on the grounds of Horyuji Temple in Nara. Recently, however, I read two papers concluding that Warner was not the person responsible for saving Kyoto and Nara from bombing, and it is said that Warner himself had also dismissed the claim. So why did this legend of Warner as savior take root? One of the studies I perused put forth the idea that the Japanese interpreted Warner’s denials as modesty, but that was not the only factor. Another major reason is that the Japanese understandably assumed that, had Warner wanted to save Kyoto and Nara, he was in a position at the time where he would have been able to do so.

Dr. William H. Furness and Dr. Hiram M. Hiller (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology)

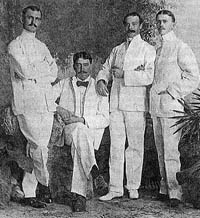

Hiller (far left) and Furness (second from left)

While Morse was giving impassioned lectures about Japan throughout Boston, William Furness and Hiram Hiller were studying at Harvard. These two young physicians were wealthy, academically successful, and brimming with a thirst for knowledge. In 1895, they departed the United States, using their own funds to search for the fabled headhunters of Borneo in the goal of obtaining ethnological artifacts for the newly established University of Pennsylvania Museum. On their way there, they stopped at Yokohama, Amami, and Okinawa, before arriving in Borneo eight months after their departure from U.S. soil. They spent four months in Borneo, and the present-day University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology holds 57 artifacts and 3 diaries the two men brought back from Amami and Okinawa.

There is an interesting statement on page 95 of Life in the Luchu Islands, a diary written by Furness:

The men of Okinawa are lazy and shiftless. They make their wives do all the work, while they drink liquor and play the shamisen. There are, of course, some men who serve as day laborers to do the rough work, such as repairing walls and roads. But perhaps because they enjoy a life that is easygoing and free of toil, many of the men – particularly younger males – can be confused for women, given their soft facial features, kind eyes, and smooth skin. Before we learned to tell the difference between the sexes based on how they tie their hair, there were times when we would see a woman on an approaching boat and cry out in astonishment at her beauty. Once the boat came closer, however, we would realize our mistake – the person we had thought was a woman was actually a man.

The men of this strange land, who appeared so lazy at a glance that they could be mistaken for women, enjoyed a genteel life of liquor, song, and dance. Can it not be said that their lifestyle gave birth to modern-day Okinawan culture and arts? It is believed that this lifestyle has a basis in unaigami worship (the belief in sister goddesses and that sisters on earth should serve as their brothers’ protectors) and the idea that it was virtuous for a woman to work for a man or other relatives.

The Expansion of Morse’s Network

So why were so many Harvard alumni influenced by Morse to the point that they took a deep interest in Japanese art? To begin with, it is believed that Morse was extremely charismatic, both as a scholar and as a person. Secondly, Salem had from long ago prospered as a trading port, meaning that rare things from all corners of the earth – both natural and man-made – regularly appeared in the town during the Age of Sail, spurring interest in foreign cultures and civilizations.

A third factor was the sense back at the turn of the century that those with wealth and knowledge had an obligation to give something back to society. Many museums for ordinary people were constructed during this time, and the items on display often came from the donations and cooperation of well-to-do patrons.

A fourth reason was the fact that Japan was then opening itself to the world and westernizing, shedding much of its older culture and civilization in the process – this was an era in which the effects of Darwinist thought had begun to penetrate Japanese thinking and views of history. In such an age, Morse and his disciples found it deeply meaningful to collect and preserve those artifacts and works of art that were being both figuratively and literally discarded.

A fifth reason was that this was a time of money-worship and materialism in the United States – the Gilded Age, an era when industrialization was inextricably linked to spiritual challenges. Among East Coast intellectuals, in particular, many were moved by the Japanese spirit, and they tried to understand it through Japanese artifacts and art.

The last reason is that this was also the end of an era, the time when the Ryukyu Kingdom collapsed and Okinawa became just another Japanese prefecture. Because of this historic development, artifacts from Okinawa were collected in order to document the disappearing culture and civilization of the Ryukyu Kingdom.

Morse’s passion for ethnology combined with circumstances in the United States, Japan, and Okinawa in the 1870s, and the Harvard scholars Morse trained collected Okinawan artifacts and art at the critical historical juncture that the end of the Ryukyu Kingdom represented. These works are at present carefully preserved in U.S. museums.

Fuji Takayasu, cultural asistant, Consulate-General Naha. Began work in the consular section in 1984 and has been in her current position since 1999. Received her master’s degree in history from the University of the Ryukyus in 2005.

This is a fascinating article. Thank you very much for sharing it. I am a PhD student at the University of California at Santa Barbara, and am very much interested in the history of Okinawan art & artifacts, and issues of Okinawan heritage & tradition.

I would be very interested if you could direct me to any other publications by Ms. Fuji, and/or to the MA thesis referenced here. I have tried a bit of searching on my own, but not knowing the kanji for Ms. Fuji’s name makes it difficult to find anything she might have published in Japanese.

Yutashiku unigeesabira. Much obliged.

Ah. Apologies. I am embarrassed to have not found the Japanese language version of this article before posting the above comment. Even so, if you could point me towards other publications by Ms. Fuji, it would be much appreciated. Thank you very much.