This article is part of a three-part series on how federalism works in America. Other installments focus on local and state governments.

Federal laws in America apply across the country in every state and city. Congress and the president have important roles to play in making and enforcing those laws, but they are not alone.

“We do need a State Department. We do need a Department of Defense,” says Karla Jones, director of international relations and federalism at the American Legislative Exchange Council, referring to the federal entities responsible for implementing the country’s foreign and defense policies.

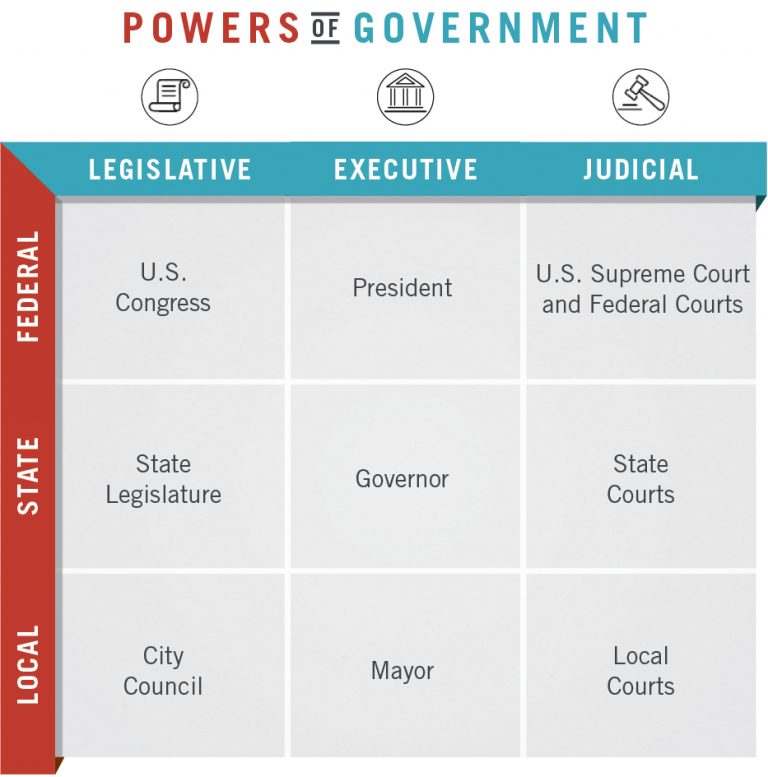

The U.S. relies on a system called “federalism,” in which government powers are divided among local, state and national responsibilities. It’s an important concept to understand because citizens encounter different levels of government daily, but in several ways.

What does the federal government do?

Only the federal government can regulate interstate and foreign commerce, declare war and set taxing, spending and other national policies.

These actions often start with legislation from Congress, made up of the 435-member House of Representatives and the 100-member U.S. Senate. Each of the 50 states receives two senators regardless of its population size. The number of representatives each state receives depends on the state’s population. Bills that Congress approves then go to the president to sign into law or reject with a veto.

The executive branch is responsible for enforcing the laws Congress makes. It is made up of the president and his or her advisers, as well as multiple departments and agencies. The departments are each headed by a secretary, whom the president appoints with the advice and consent of the Senate. The U.S. has more than a dozen departments, and they each take on a specific set of duties. The Treasury Department’s duties, for example, include printing and regulating money.

The president also serves as commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces. That means the president directs how military weapons will be used, where to deploy troops and where ships are sent. The military’s generals and admirals take their direction from the president.

This graphic summarizes the kinds of entities in each branch of government.

(State Dept./J. Maruszewski)

The Supreme Court is the highest federal court in the U.S. and assures the American people of equal justice under law. The court’s nine justices — one chief judge and eight associate judges — interpret the law, in a fair and impartial manner, when disagreements arise on the legality of a law that Congress approves, a regulation that a federal agency implements or other matters.

The Constitution empowers the president, who is elected by the entire nation, to nominate justices. These justices require Senate confirmation to uphold the checks and balances among the branches of government.

“The Founders separated power because they knew it was the best way to protect our citizens and keep our Constitution secure,” President Trump said at the April swearing-in of Justice Neil Gorsuch, whom the president nominated to the Supreme Court.

Landmark decisions from the Supreme Court shape American life, and their ramifications are still felt today. They include the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, which outlawed racial segregation in public schools.

The three branches of the federal government get together at the U.S. Capitol when the president delivers the State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress. That speech represents an opportunity for the president to lay out an agenda for the coming year. These addresses are traditionally held in January or February after the new session of Congress convenes. President Trump’s first State of the Union address is scheduled for January 30, 2018.

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP