As he descended into the blue and the Aquarius habitat appeared before him, covered in sea life like an outcropping of the reef, Japanese astronaut Norishige “Nemo” Kanai thought, “This is my dream-come-true moment.”

Ten years before, as a Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) dive surgeon training with the U.S. Navy, Kanai had learned that NASA sent astronauts to live in the underwater laboratory as part of its NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations (NEEMO) program.

Scientists and astronauts can stay up to two weeks in the Aquarius Undersea Habitat, the world’s only undersea laboratory, at the edge of a reef in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, near Key Largo. It is owned and operated by Florida International University’s Institute of the Environment.

Aquarius habitat, home to the NEEMO 20 crew for 14 days (Photo courtesy of NASA)

NASA uses NEEMO and other “analog missions” in Antarctica, the Arizona desert, Canada’s Devon Island, on the Hawaiian volcano Mauna Loa, and other locations to test technology and observe how people work and live in isolated and extreme environments similar to what astronauts might experience on Earth’s and other moons, Mars, an asteroid, or the International Space Station (ISS).

Kanai, the latest Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) astronaut to participate in an ISS mission, hadn’t always aspired to go to space. “When I was a child, I never thought about becoming an astronaut,” he said in an interview with American View. “It was beyond my dreams, beyond my thoughts. I just got lucky.”

As a young man, he joined the JSDF and went to medical school to become a surgeon, specializing in dive medicine. The JSDF sent him to the U.S. Naval Diving & Salvage Training Center in Panama City Beach, Florida, for additional training. He learned that many NASA astronauts had backgrounds in undersea or aviation medicine. “I thought, ‘wait a second,” he recalled. “I’m a Japanese medical officer, and I studied underwater medicine. I could be an astronaut.’”

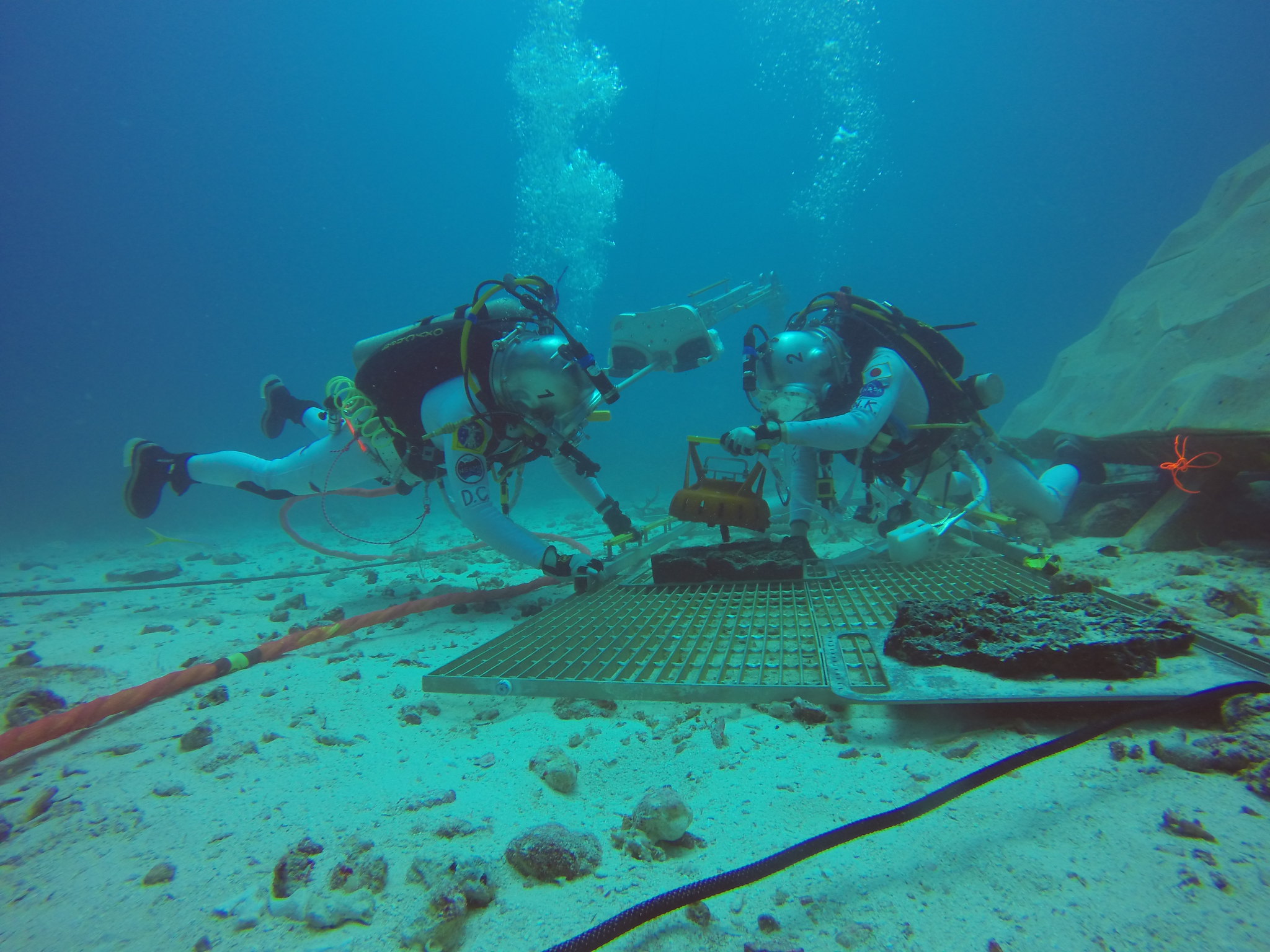

Crew attaching JPL's microspine to a rock to use for body stabilization while collecting samples (Photo courtesy of NASA)

Kanai was selected to be an astronaut in 2009, completed his training two years later (that’s when he received his nickname, Nemo, after the fish from the popular movie), and was assigned to take part in a NEEMO mission that began in July 2015. With two other astronauts and a trainer, Kanai took a boat to a buoy that contains the equipment to sustain human life and work in the habitat. They stepped off the back of the boat and followed the support tether 29 meters down to the Aquarius habitat, which rests on a base about 4 meters off the seafloor. Now he was an “aquanaut.”

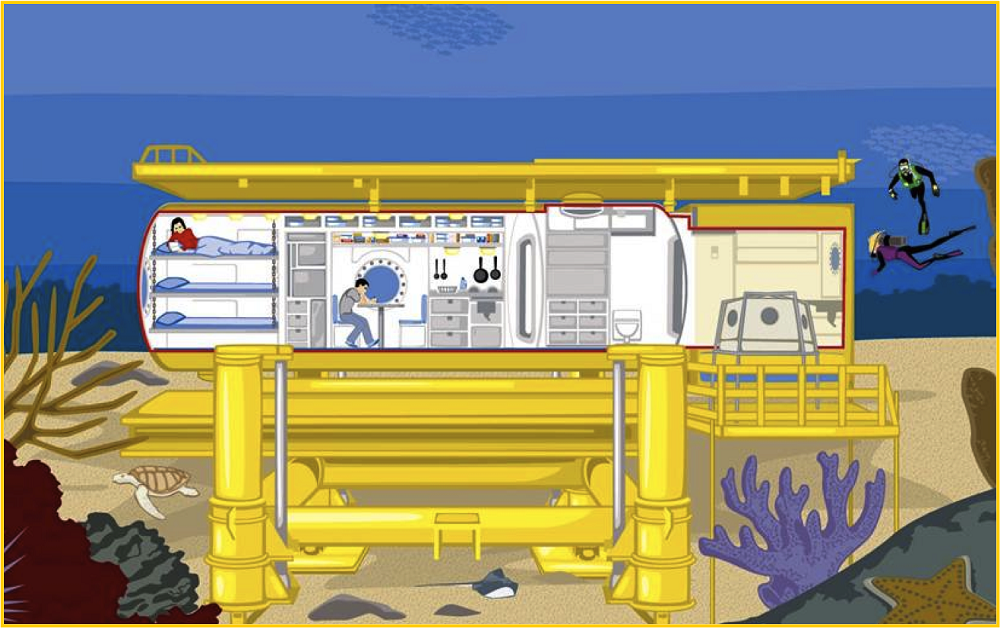

They entered the habitat, which is about the size of a bus, by way of a “wet porch,” one of four compartments. There’s also a lab area, a compartment room with a microwave, table, and seats, and a sleeping area with six bunks.

Aquarius interior and exterior (Photo courtesy of Florida International University)

By living in the habitat, at the same 2.5 atmosphere pressure as the seafloor where they worked, the aquanauts’ bodies become saturated with gas, enabling them to work for up to nine hours at a time without the need to decompress. Ordinarily, a scuba diver needs to resurface after an hour or so. A portable “gazebo” like metal air bubble, enables divers to take a break without even leaving their work site.

NEEMO 20 crew (Photo courtesy of NASA)

Daily life was busy with experiments submitted by schools and scientists, technology companies, and national space programs from around the world. The aquanauts tested equipment that could be used to work in space outside the protection of a spacecraft or module. In one experiment to test decision-making, the aquanauts performed tasks for which instructions from “mission control” were delayed like they would be in transmissions from Earth to Mars or the asteroid belt. “It was frustrating, but with good tactics we could manage that boring waiting time in a constructive way,” Kanai said. “During the waiting time we could do plan B, plan C, then come back to plan A when we got the answer from the ground.”

After 10 days, Kanai’s NEEMO mission ended with an overnight decompression in the habitat, safely releasing the gases saturating his body, before he could surface to sun and fresh air and other people.

Two and a half years later, Kanai received his next big opportunity: to launch atop a Soyuz rocket from a pad in Kazakhstan to the ISS, 400 kilometers above the Earth’s surface.

In orbit, he had a long list of experiments to perform. One was to study how microgravity affected the aging of mice, including changes in bone density and muscle mass, and the working of DNA – processes that are crucial to understand whether it would be feasible to send people for years at a time to the Red Planet. He also conducted a spacewalk with another astronaut in which they repaired the ISS’s robotic arm.

Scene from the spacewalk on February 16, 2018 (Photo courtesy of NASA)

As in Aquarius, Kanai lived and worked closely with just a few other people for an extended time– six months-- and built close bonds with them. Still, they were much more isolated than the aquanauts were.

“Aquarius always had a lot of visitors. Divers came to the Habitat every day to drop off equipment, food, necessary items, but on the space station, there was no contact with the ground, only indirect contact using communications, or with the cargo vehicles,” he said.

As a result, the crew members felt like family, and it was bittersweet when, five months after docking with the ISS, Kanai and two of his five colleagues crawled into a capsule to drop out of orbit and fall to Earth, hitting the Kazakh plain “like a car crash.” The hatch opened, fresh air blew in, and, “it was overwhelming, the number of people smiling, waiting, helping us out of the capsule,” he said.

In August 2019, Nemo Kanai participated in another NEEMO project beneath the sea off the California coast, to test equipment for a moon mission. He is also doing JAXA public relations and training to work as a flight controller, using his valuable experience to support future missions. Since he’s already lived on the seafloor and orbited the Earth for extended periods, maybe his next challenge will involve traveling to another world.

“If possible, I would like to go to Mars to experience for myself the long duration,” he said. “It’s completely different from the space station. The space station is like a habitat; it’s very nicely controlled, equipped, and very comfortable. Probably going to Mars is harder, more stressful, but I think, still, we can manage these problems.”

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP