Pandemic or no, Americans last week commemorated the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a culmination of the movement that pushed for important U.S. civil rights laws.

They did so online and in events organized around the United States as well as in Washington, where an estimated quarter-million people flocked on August 28, 1963.

Many were inspired by the graphic novel trilogy called March, co–authored by the late Congressman John Lewis and published serially from 2013 to 2016. The series is a bestseller, and the third book of the trilogy is a National Book Award winner.

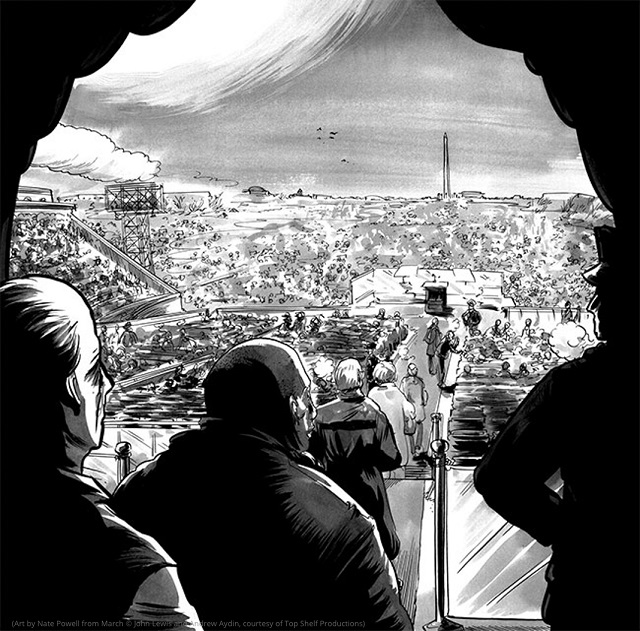

The 1963 March on Washington (Art by Nate Powell from March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy of Top Shelf Productions)

At age 23, Lewis was the youngest speaker at the Lincoln Memorial on that August day 57 years ago, addressing the crowd immediately before Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

ShareAmerica reached out to Lewis’s collaborators on March, co-author Andrew Aydin and illustrator Nate Powell, to learn about their artistic partnership with the late congressman.

It all started years ago, when Aydin, then an aide in Lewis’s office, told his co-workers that he planned to attend Comic-Con, an annual convention of comic book creators and fans. Aydin’s peers teased him about it, until Lewis stepped in to say that a 1957 comic book about King had influenced his own journey, from young activist to long-term member of the U.S. Congress.

Aydin suggested that Lewis narrate his experience for a comic book. But Lewis, already the author of a memoir titled Walking With the Wind, was skeptical. “It took some convincing to persuade Congressman Lewis that a comic book was the right path for bringing the history of the civil rights movement to new generations, but once he became convinced, he embraced the idea with his whole being,” Aydin says.

Creating a modern classic

Aydin remembers interviewing Lewis after work or on weekends. Along the way, he showed the congressman how the script was coming along and asked for his feedback.

Powell, left, and Aydin, right, pose with co-author Lewis on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. (© Sandi Villareal)

As each volume was published, the three collaborators appeared together at speaking events. Sometimes, “an audience question or something about the place we visited would spark a memory” for Lewis, “and he would say, ‘We have to make sure that’s in there,'” Aydin says.

Powell — who rendered his illustrations in black, white and shades of gray, evoking the TV news footage of the civil rights era — describes the collaborative process as “very intensive,” requiring three-way communication at every step.

“From Andrew’s script, I’d typically cross-reference details with other historical accounts” and Lewis’s earlier memoir, while digging up photos from the civil rights era, Powell says. “The entire process was immersive,” with new details from Lewis whenever the three men traveled together, which was often.

Powell grappled with how to depict the violence endured by civil rights activists as they protested against segregation and the denial of African Americans’ voting rights.

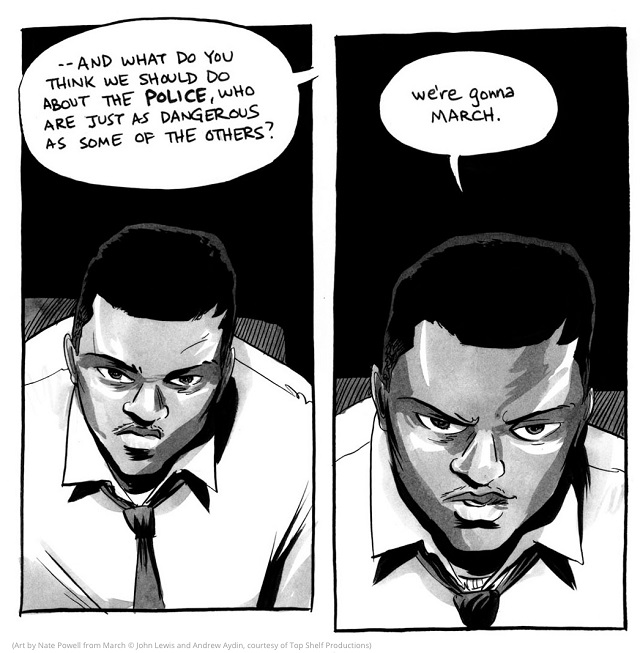

A young John Lewis shows resolve. (Art by Nate Powell from March © John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, courtesy of Top Shelf Productions)

“If a violent sequence conjured feelings of disgust, horror or anxiety in me at the drawing table, I knew I was conveying the scene correctly,” Powell says. “Violence is ugly and horrifying, so I kept my process quick and raw.”

‘A happening’ … and a lesson

After the publication of March, Aydin — still a Comic-Con devotee — found it great fun to introduce Lewis to the festival. “Congressman Lewis loved going to Comic-Con. He would call it ‘a happening,'” Aydin says. “He loved people, and being around a whole new group of people was fascinating for him. I remember the joy on his face, seeing the line for his autograph at his first Comic-Con.”

Lewis especially enjoyed re-creating his famous protest marches when meeting children at comics festivals, Aydin recalls.

“Leading the marches through Comic-Con was unreal,” Aydin says. “We would set out with a few hundred students, and by the time we reached the convention floor, there were thousands of people marching with us. … We were trying to show new generations how to march so that they would be ready and prepared to carry on the struggle.”

The March trilogy — now featured in many school curriculums — shows how young people, decades ago, produced necessary changes in their society. Today, Powell says, “any young person must understand that this moment in their lifetime is not a drill, and it never was.”

The late Congressman John Lewis, flanked by illustrator Nate Powell, left, and co-writer Andrew Aydin, walks with young fans at Comic-Con in 2017. (© Carlos Gonzalez/The New York Times)

Banner image: The late Congressman John Lewis, flanked by illustrator Nate Powell, left, and co-writer Andrew Aydin, walks with young fans at Comic-Con in 2017. (© Carlos Gonzalez/The New York Times)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP