When Crystal deGregory was growing up in the Bahamas in the 1990s, she learned about Fisk University, a historically black university in Tennessee, from her math teacher and other professionals.

But by the time she was a senior in secondary school, deGregory didn’t think she was a candidate for higher education. Her allergies had made her miss classes, hampering her academic progress. And her school’s culture didn’t suit her.

But Fisk University’s then-director of admissions, Anthony E. Jones, visited deGregory’s school on a recruiting trip. “He was undaunted by those very real realities. He was convinced that I would succeed at Fisk, and he convinced me of the same,” says deGregory, founder of HBCUstory.org, a website with stories about historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

deGregory holds a bachelor’s degree from Fisk University, master’s and doctoral degrees from Vanderbilt University and a master’s from Tennessee State University. (Courtesy of Crystal A. deGregory)

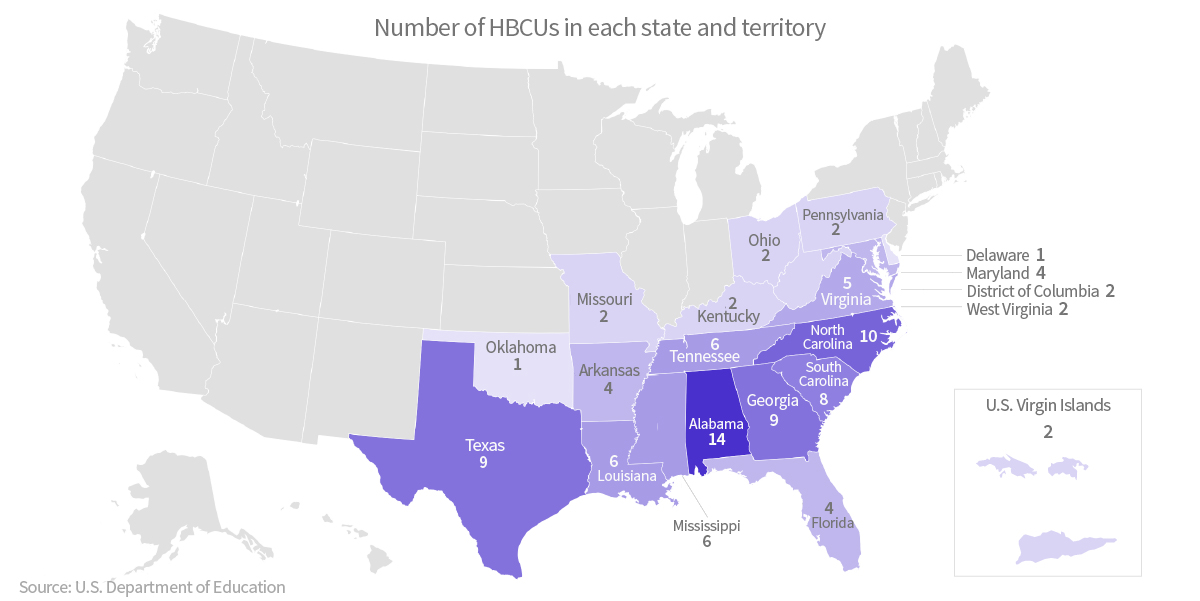

Fisk is one of 101 schools the U.S. Department of Education recognizes as HBCUs. These schools were established before 1964 primarily to educate African Americans and are accredited by a nationally recognized organization. The Higher Education Act of 1965 coined the term “HBCU” and expanded federal funding for the schools.

Recent graduates of Fisk University, in Tennessee, respect their academic forbears. (© National Geographic Image Collection/Alamy Stock Photo, © Glasshouse Images/Alamy Stock Photo)

Some are four-year universities while others are two-year community colleges. They include everything from law and medical schools to schools offering degrees in liberal arts or theology. Students of all races can attend HBCUs, and not all HBCUs are predominantly Black. Nearly 300,000 students attend HBCUs.

While they enroll 10 percent of all African American college students, HBCUs churn out almost 20 percent of African American graduates and 32 percent of African American STEM graduates (science, technology, engineering and math), according to the United Negro College Fund, a philanthropic organization.

The first HBCUs — Wilberforce University in Ohio, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania and Lincoln University also in Pennsylvania — were established in the North before the U.S. Civil War, when discrimination blocked Black students from traditionally white schools. These HBCUs trained Black teachers, ministers and tradespeople.

After the Civil War and Reconstruction (1865–1877), HBCUs were formed in the Southern states to create an educated class among newly emancipated enslaved people, says Sydney Freeman Jr., an associate professor at the University of Idaho.

Today, the HBCUs retain a reputation for excellence. “Each institution is unique and is an important part of this country’s educational fabric,” U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said in a statement.

Alumni make their mark

With their large endowments and active alumni, the most well-known HBCUs are Howard University in Washington, Spelman College, an all women’s college in Georgia; Morehouse College, an all-men’s college near Spelman; and Hampton University in Virginia. They and the other HBCUs have long graduated alumni who become renowned.

Civil rights hero Diane Nash was studying at Fisk when she organized the Freedom Rides, which pulled students and alumni from other HBCUs, including future U.S. Representative John Lewis from American Baptist College and Margaret Winonah Beamer Myers (a white student) from Central State University. Their activism helped desegregate interstate bus facilities.

Diane Nash, center, leads demonstrators protesting police brutality in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1961. (© Eldred Reaney/The Tennessean-USA Today Network)

Bayard Rustin, a Wilberforce and Cheyney alumnus, helped organize the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the March on Washington at which Martin Luther King Jr., a Morehouse College graduate, delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech.

In 1954, Howard University law graduate Thurgood Marshall and a team of other attorneys ended segregation in public education by winning the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, lawsuit at the U.S. Supreme Court. (Marshall became a Supreme Court justice in 1967).

”There’s no way you can talk about the civil rights movement without talking about HBCUs — it’s impossible,” says Leslie Jones, a Howard graduate and founder of The Hundred Seven, an organization that promotes HBCUs.

Thurgood Marshall outside the U.S. Supreme Court during the time Brown v. Board of Education was argued at the court. Years later he joined the Court. (© Hank Walker/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Recently, several HBCU-educated attorneys have begun preparing cases against indicted killers of Black people. For instance, L. Chris Stewart (Xavier University and Howard University School of Law) represents Rayshard Brooks‘ family in Georgia. (Brooks, a 27-year-old Black man, was shot and killed by an Atlanta police officer on June 12. The officer was fired and charged with murder).

Texas Southern University, another HBCU, reserved a full scholarship for George Floyd’s 6-year-old daughter when she’s college-aged. (Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, was killed by police during a May 25 arrest in Minneapolis. The officers were fired and charged with murder or other felonies).

As impressive as it is to graduate activists and legal experts, HBCUs are best known for giving students like deGregory a greater sense of possibility. In 1999, deGregory became the first in her family to enroll in a university. Jones, the recruiter (now associate provost at Howard University), helped deGregory win a partial scholarship to Fisk and promised her mother he’d put deGregory on a plane back home if she couldn’t cut it. That mother trusted him, and the school, Jones recalls.

***

If you want to study in the U.S., find resources at EducationUSA.

Banner image: Members of the Howard University Gospel Choir perform at the MLK Event at Washington National Cathedral. Washington, DC, January 20, 2014. (Shutterstock)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP