“I was considered a troublemaker,” Ambassador Terence A. Todman said of his time at the State Department, “and that was all right.”

Todman (1926–2014) was one of the first Black Americans designated a career ambassador, a classification appointed by the president for distinguished service.

He paved the way for nonwhite diplomats at the Department of State. In his career, he fought for Black diplomats and challenged institutional racism.

Todman was born in St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands to a laundress and a grocery store clerk — one of 13 children. He was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1945, where he served for four years.

Todman began his State Department career in 1952, more than a decade before the Civil Rights Act. At the time, there was only one other Black diplomat at the State Department.

“I remember people coming to my office for meetings, and they’d come and say, ‘We’re here to see Mr. Todman,'” he recalled, “And I’d say, ‘Well, I’m Mr. Todman, come on in.’ And it was, ‘You’ve got to be kidding!’ It took them a little while, several people, to accept the fact that I could be the person responsible for some activities. It was a different world.”

Todman started in the Foreign Service in 1957. During his training at the Foreign Service Institute (FSI), Todman encountered ugly facts of the still-segregated South.

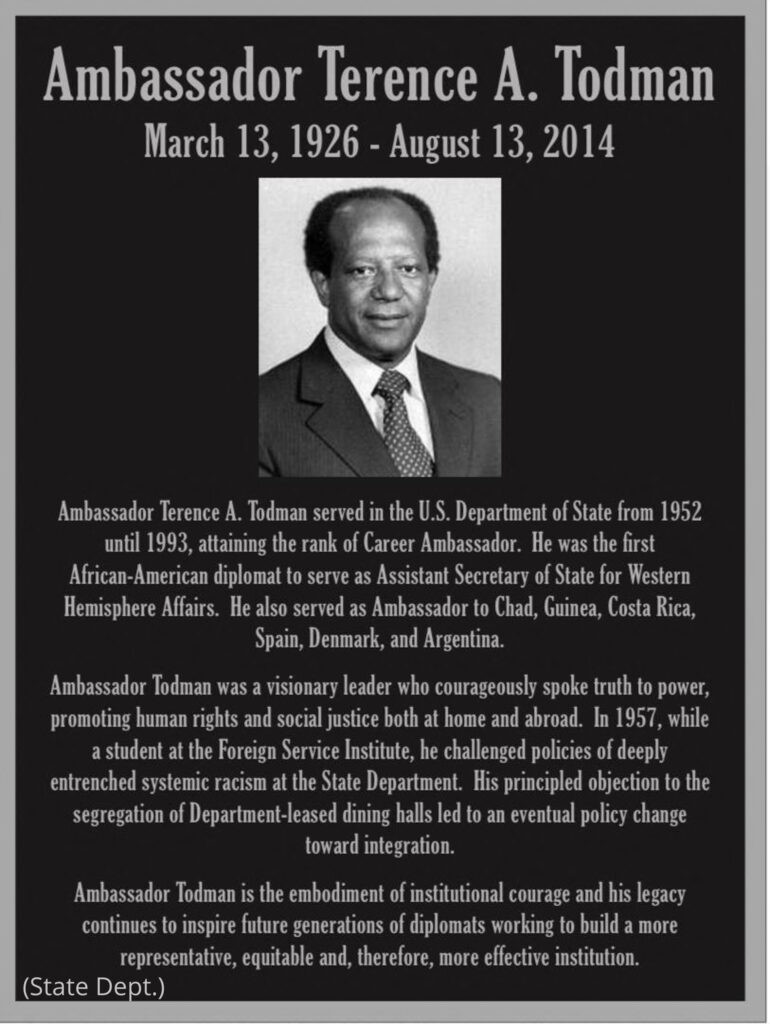

A plaque honoring Todman’s legacy. (State Dept.)

At the time, the FSI campus was located across the Potomac River from Washington in Rosslyn, Virginia. At the time, Virginia was segregated, meaning Black people were not allowed inside restaurants or to use the same public facilities as white people.

“I discovered that the only thing [FSI] had for any meal arrangement was a very small coffee shop where you could basically get some coffee cake and some coffee, tea or whatever,” he said. “And at lunchtime, all of the white officers went across the street to a regular Virginia restaurant and had their meals.”

When Todman raised the issue of not being able to eat a full lunch with his white colleagues, he met with resistance. He pursued the issue within the department until it reached the office of the undersecretary for management.

The State Department finally agreed to lease half of the restaurant and erect a partition. The same kitchen and staff were used for all customers, but half of the restaurant was leased by the State Department — which meant it wasn’t segregated and Todman could eat a full lunch there — while the other half remained a private restaurant.

In the years that followed, Todman’s career as a foreign service officer led to his appointment as one of the first Black U.S. ambassadors, and he acted as a human rights activist everywhere he served.

From 1969 to 1993, Todman served as the U.S. ambassador to six different countries: Argentina, Chad, Costa Rica, Denmark, Guinea and Spain. The Carter administration also appointed Todman as the assistant secretary of state for Inter-American Affairs in 1977.

In a 1995 interview (PDF, 220 KB), when asked about the future of the State Department, Todman said creating more diversity among diplomats was essential. “We need, as a country, the very best input that we can get into policy formulation and policy implementation,” he said. “There are sensitivities that people bring into a meeting that you can’t get otherwise.”

The U.S. State Department honored Todman’s legacy on February 1, 2022, with an event featuring Ambassador Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley, the chief diversity and inclusion officer. For more stories of diversity in diplomacy, please visit the National Museum of American Diplomacy’s Facing Diplomacy initiative.

Banner image: Terence A. Todman became one of the most senior Black members of the Foreign Service during his four decades in diplomacy. (© Frank Johnston/The Washington Post/Getty Images)

The original article is here on ShareAmerica.

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP