The U.S. presidency and both chambers of the legislature are currently controlled by Republicans — one of two main political parties in the U.S. The situation can help a party to pass laws that support its causes, but it doesn’t mean proposals sail through unhindered.

A combination of traditions, “checks and balances” and math all factor into how a bill becomes a law.

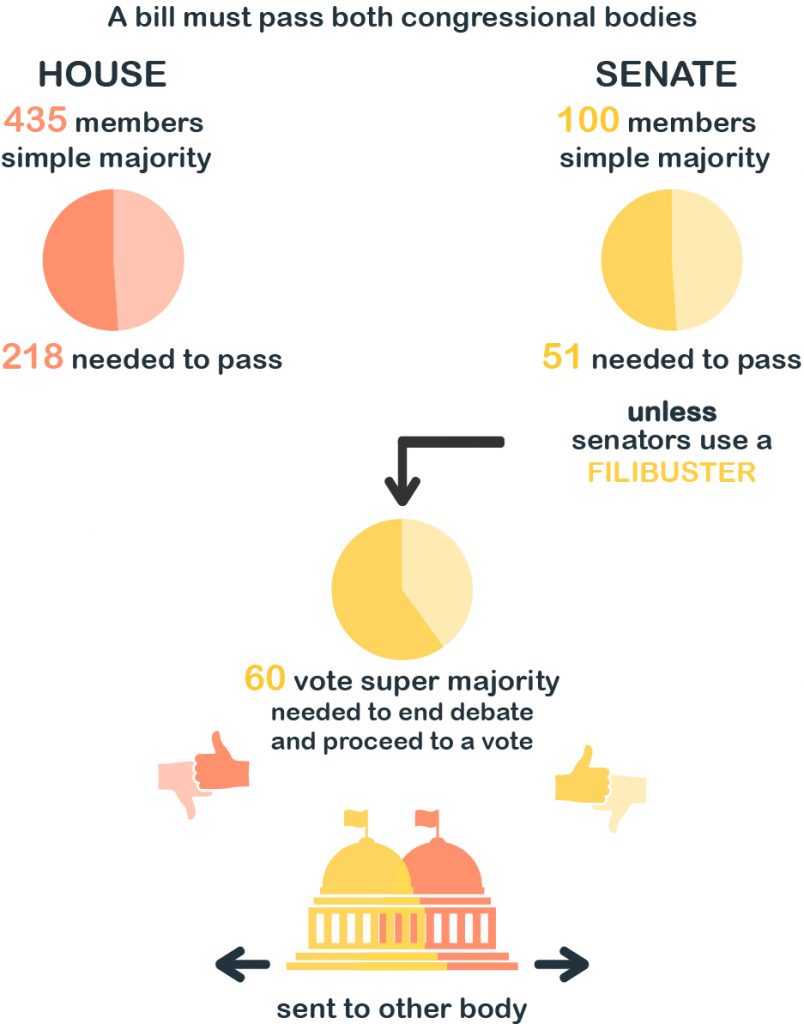

Let’s start with the math part. The 435-member House of Representatives passes legislation by majority vote, which means at least 218 House members need to vote in favor of a bill for it to pass the House.

It’s more complicated in the Senate, which has 100 members. A group of senators can “filibuster,” or keep a proposal from coming to a vote, unless 60 senators agree that it’s time to stop talking about the measure and agree to a vote.

So, for instance, in the current U.S. Senate, the 52 Republicans need eight Democratic votes to get past the filibuster and vote on a bill. Once there are enough votes to end a filibuster, the Senate still needs to take a formal vote to pass the bill, but only a majority (51 votes) is needed. If the legislation isn’t controversial and a senator doesn’t use the filibuster, a majority vote suffices to move the bill along.

President Trump would like the Senate to get rid of the filibuster and go to a 51 percent majority for any proposal to pass the Senate. Otherwise, he says, few bills will be passed.

Donald Ritchie, historian emeritus of the U.S. Senate, predicts senators are unlikely to change the rule that allows for filibusters. “It makes every single senator a powerful player,” he says.

In the old days, senators talked all night during a filibuster to prevent votes. In recent years, all senators have needed to do is threaten a filibuster before the leadership backs off. (The majority party isn’t too keen to stay up all night watching the other side speak if they know they don’t have the votes to stop it, Ritchie says.)

The filibuster serves a broader purpose than stopping particular legislation. It fosters a Senate tendency to find bipartisan compromise. That makes the Senate a very different place than the House, where the tradition during the past 20 years has been for the majority party to focus on legislation that can pass without any help from the other political party.

Once the Senate and House pass their own bills on a topic, the two different versions are worked out. If the compromise they come up with is passed by both the House and the Senate (they vote again), the bill goes to the president next. Getting that far is rare, Ritchie points out: The U.S. system “was never designed to be easy.” (Even when the leadership of the House and the Senate are in the same party, they aren’t always on the same page about legislation.)

But House and Senate rules aren’t the only factor. The president and the courts also have important roles to play. That gets us to the “checks and balances” of the U.S. Constitution, which exist to make sure one branch of government doesn’t have too much influence.

When legislation does pass Congress, it goes next to the White House, where the bill’s monthslong or yearslong journey can end with a stroke of the president’s pen. If the president signs the legislation, it becomes law.

If the president rejects the legislation, or vetoes it, it isn’t necessarily the end for the bill. Congress can override the president’s veto with a two-thirds vote in both the House and the Senate. This “check” prevents the president from blocking an act when there is significant support for it. Historically, Congress has overridden less than 10 percent of all presidential vetoes.

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP