While presidents often first sweep into office with their party controlling both the House and Senate along with the executive branch, every president since 1980 has faced divided government, with the opposing party capturing the majority of at least one chamber of Congress, for at least some of his tenure.

That sort of division is not possible in many countries, but in the United States “it is not at all unusual,” says Alan Abramowitz, a professor of political science at Emory University and an elections expert.

The American founders all those centuries ago envisioned the House of Representatives (where the minimum age is lower and terms only last two years) to be more in tune with the public and the Senate (with six-year terms) to be a stabilizing counterbalance. “When the chambers are in the hands of two different parties, the differences are magnified,” says Ross K. Baker, a professor of political science at Rutgers University.

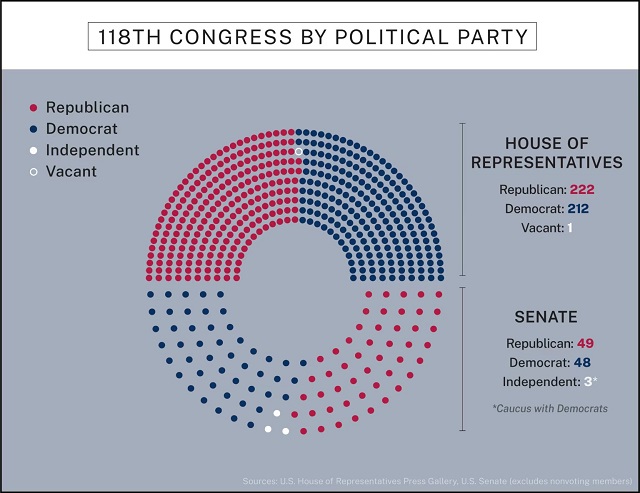

The new — divided — Congress that took office in January isn’t hugely different from the previous version, but a nine-seat change in party representation flipped control of the U.S. House of Representatives to the Republicans. Republicans won 222 seats to 213 for Democrats, though one elected Democrat has since died, leaving Democrats with 212 seats.

Democrats still control the Senate — with 51 votes instead of last term’s 50 plus the tie-breaking Vice President Harris. (The Democratic caucus, or voting bloc, includes three independents who vote with the Democrats.)

(State Dept./M. Gregory)

President Biden, a Democrat, stays in the White House until he (if reelected) or another elected presidential candidate begins the next four-year term in January 2025.

So why do American voters choose people of different political persuasions to run different parts of the government? Abramowitz says it’s a function of a very close divide among Americans between the two parties. And he points out that while some voters chose candidates based on their party, many independent (“swing”) voters choose based on the particular candidates in their district. “The party balance is the outcome of so many different elections,” he says.

Divisions beget compromise

Divided government highlights a wariness voters have of politicians as a group, according to Baker, even when voters like their own local representative. “They feel stalemate is a good thing.”

The practical effect of different parties in the White House and the House of Representatives will mean enacting legislation will require compromise.

In the near term, “it’s going to be difficult, if not impossible, for the president to get parts of his legislative program enacted,” Abramowitz says.

Had the Republican party picked up a bigger slice of the House, it might have looked forward to pushing a heftier agenda of policies. “Republicans have a handful more members, but it isn’t a mandate,” Baker says.

Abramowitz says that within Congress, the switch to Republican control of the House means that the party can control what legislation is voted upon and use its investigative powers to dig into things the party doesn’t like. Republicans will control the many committees and subcommittees that oversee budgets and policies. On each committee, a Republican will fill the chairman’s seat and the party will seat a majority of the committees’ members and employ more staffers than will members of the Democratic party.

The U.S. House of Representatives held a historic number of votes in early January 2023 to choose its next speaker. (© Andrew Harnik/AP)

The advantages matter. For instance, the majority party controls the powerful House Rules Committee, giving it leverage over which proposals come up for a vote and what amendments to proposed bills are allowed on the House floor for debate.

But with only 10 more votes than Democrats have in the House, Republicans will need to hold together to wield any power. Conservative firebrands on the one hand, and moderate Republicans on the other, will need to compromise, Abramowitz says. “The key is 218 votes.”

The majority party chooses a speaker, or leader, of the House of Representatives. The speaker traditionally has held considerable sway, especially when his or her party projects a united front. (The speaker is also second in the line of succession behind the vice president.)

After 15 votes, a majority of House members chose Republican Kevin McCarthy, who represents a district in California, as speaker. In doing so, they agreed to give more clout to small groups and even individual Republicans. The agreement allows just one Republican to call for a vote to oust the speaker. Such rules — as well as committee assignments — can be changed with each new session of Congress.

Senate sway over the judiciary

In the Senate, Democrats will run committees, but stricter rules there require supermajorities (well over the 51 votes that the Democrats control) to pass many measures.

Still, Democrats’ slim control of the Senate will mean that Biden will be able to get judicial and executive branch appointees confirmed more easily, since the Senate (without the House) controls the judicial confirmation processes.

If a seat opens up on the U.S. Supreme Court, for instance, Biden could have a lasting impact since his nominee, if confirmed, would serve for life. “It’s hugely important,” Abramowitz says.

Banner image: People walk outside the U.S. Capitol building in Washington June 9, 2022. The newly elected members of Congress recently gathered to begin their new session. (© Patrick Semansky/AP)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP