On March 3, or Super Tuesday, when millions of voters in 14 U.S. states came to the polls, we were there too. Joining journalists from around the state of Virginia and around the world covering the U.S. presidential election process, we traveled to Northern Virginia and spoke to election officials and voters about their experiences.

Civic interest starts early

Robert Mansker, chief election officer of Precinct 705 in Falls Church, Virginia, got hooked on election work early. As a high school student in 1952, he watched a party’s national convention on television and still remembers seeing how things played out. “I sat there mesmerized by the process … and I said, ‘Who’s going to win this?'” says Mansker, 79.

Tuesday’s primary was the 33rd election Mansker worked, and his job isn’t an easy one. Not only is he required to stay current on election-process rules, but he works long hours. He sets the school up for the election before dawn and turns in the results to the county after the polls close in the evening. “The interest in the issues at hand during the day keeps me coming back,” Mansker says.

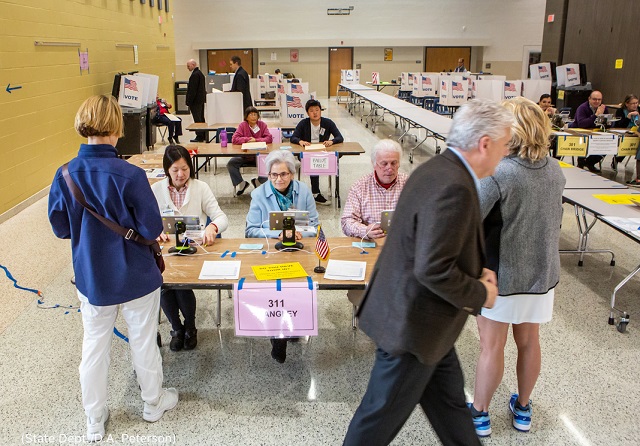

Super Tuesday voters check in with election workers at Langley High School in McLean, Virginia. (State Dept./D.A. Peterson)

Which party?

The Democratic primary in Virginia was held to help the party determine which Democrat will be the party’s candidate for president in November. But because Virginia is one of more than a dozen states with an “open primary,” it allows voters such as McLean resident Jayne Chambers, a self-described “moderate Republican,” to vote for a candidate on the Democratic slate. (In these states, a voter can vote in any primary.)

“It’s very important to vote in every election, whether it’s primary, general, local community council, whatever,” Chambers says. “That’s our right as an American.”

Voting rights

This year’s elections come 100 years after the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gave women the right to vote. “I feel very honored that I can vote; I always have felt that way,” says Angela Kolaras, 81, referencing the milestone.

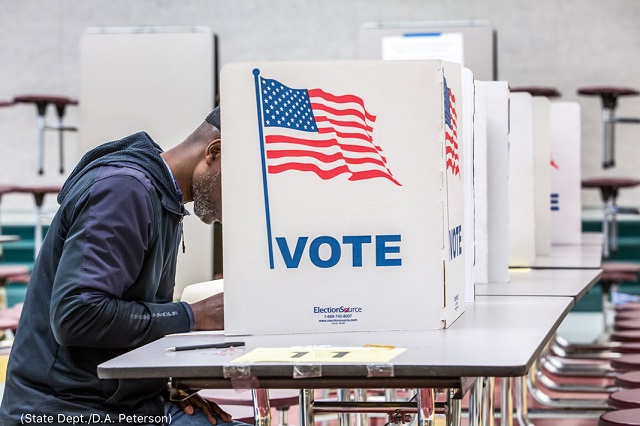

African Americans voted in large numbers across the South during the era of Reconstruction following the Civil War, and their right to vote was codified in 1870, with ratification of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution. But states found ways to disenfranchise black voters through obstacles such as poll taxes and literacy tests. It wasn’t until the 1965 Voting Rights Act that black voters were allowed to fully exercise their democratic rights.

A voter casts his ballot on Super Tuesday at Graham Road Elementary School in Falls Church, Virginia. (State Dept./D.A. Peterson)

“For me not to [vote] would be sacrilegious,” says Opal Elliott, 70, an African American woman whose parents came to the United States from the Cayman Islands.

Deborah Litman hit the polls in Falls Church with her 7-year-old son, Jaden Fetter-Litman, in tow. She has brought him with her when she has voted since the 2016 presidential election because she wants him to understand how important it is to vote. Everybody has a voice, and it’s important for Jaden to learn that early, she says. “We’re really the best country because we have this freedom — all these freedoms — freedom of speech, freedom to vote,” Litman says.

Banner Image: A polling place in Falls Church, Virginia, during the Super Tuesday U.S. presidential primary (State Dept./D.A. Peterson)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP