You’ve probably heard of Harriet Tubman, the American woman who famously led 70 enslaved people through the Underground Railroad — a network of secret passageways, routes and safe houses — to freedom in the Northern states or Canada.

Lesser known is Josiah Henson, who came before Tubman. He was born into slavery in Maryland, ran away from his owner and escorted 118 enslaved people through the network to Canada.

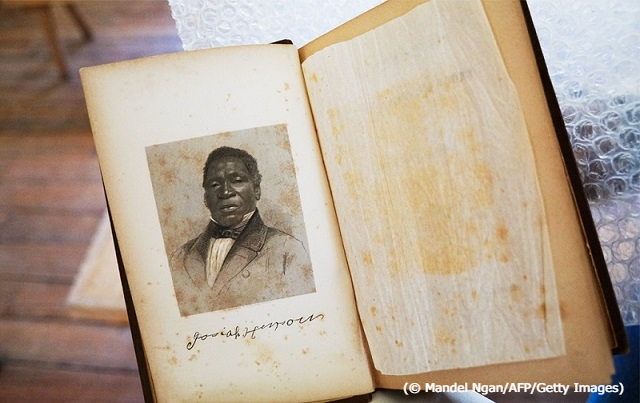

A photograph of Josiah Henson’s autobiography, featuring his photograph and signature (© Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images)

Now, the Montgomery County Parks Department in Maryland is building the Josiah Henson Museum in honor of the American abolitionist — at the same tobacco and wheat plantation on which he toiled for so many years.

The main house still stands at Isaac Riley’s plantation, now known as Josiah Henson Park. A museum in Henson’s honor will be in this house. (© Tony Ventouris/Montgomery Parks)

“We want to put him back in the spotlight and have people understand how important it is to understanding slavery in the upper South and to the abolition movement as well,” says senior historian Jamie Kuhns. The museum will open in November.

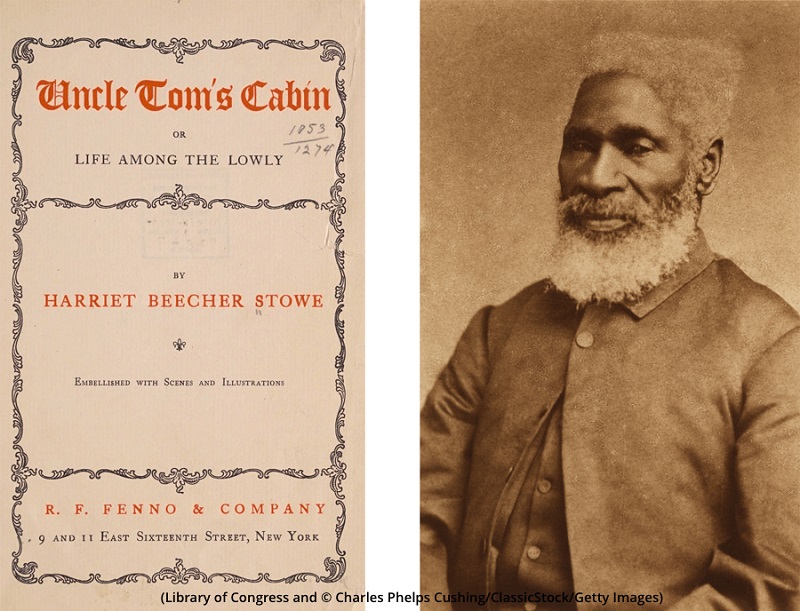

Henson’s narrated autobiography, The Life of Josiah Henson, was originally published in 1849 and inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which models its namesake character after Henson. Stowe met Henson before her book was published in 1852.

The novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” left, was inspired by Josiah Henson, right. (Library of Congress; © Charles Phelps Cushing/ClassicStock/Getty Images)

Stowe’s anti-slavery novel became the best-selling novel of the 19th century and helped ignite the Civil War, which ultimately ended slavery.

Journey to freedom

Henson’s life was full of ups and downs.

Born in 1789 in southern Maryland, he experienced slavery’s brutality at an early age.

His father attacked an overseer for assaulting Henson’s mother. As punishment, the elder Henson was whipped, his ear was severed and he was sold to another slaveholder, Kuhns says.

Henson never saw his father again. The rest of his family was split up in a sale, but Henson joined his mother on Isaac Riley’s Maryland plantation.

Besides working as an overseer and selling Riley’s produce in Washington, Henson preached in the Methodist Episcopal Church to earn $350 for his freedom. Riley tried selling him in New Orleans anyway. Later, Henson, his wife and their two youngest children escaped from slavery in Kentucky, walking more than 960 kilometers to present-day Ontario, Canada.

There, Henson helped establish Dawn Settlement, a community of 500 free blacks.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site and museum in Dresden, Canada, was built on the site of the black settlement Josiah Henson helped establish. (© Tony Cenicola/The New York Times/Redux)

He returned to the United States multiple times to guide slaves to freedom, preach Christianity and secure money for the settlement. Henson also made several trips to Great Britain to raise money and oppose slavery.

In Henson’s later years, abolitionist and U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes entertained him at the White House. Queen Victoria feted him at Buckingham Palace.

He died in 1883 at 93. “He had a lot of notoriety in his lifetime,” Kuhns says. “People knew him in the U.S. and Canada and also in England.”

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP