While each major U.S. political party has many states it counts on winning in November’s presidential election, a handful of states are too close to call.

These “swing states” have populations that are closely divided politically. They have swung back and forth between Democratic and Republican candidates in recent years. They are the battleground states that candidates will target with campaign visits, advertising and staffing.

Experts don’t always agree on which states are swing states. The Cook Political Report sees Arizona, Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin as toss-ups. Other experts would add New Hampshire, North Carolina and a handful of others to the list.

Swing states and the Electoral College

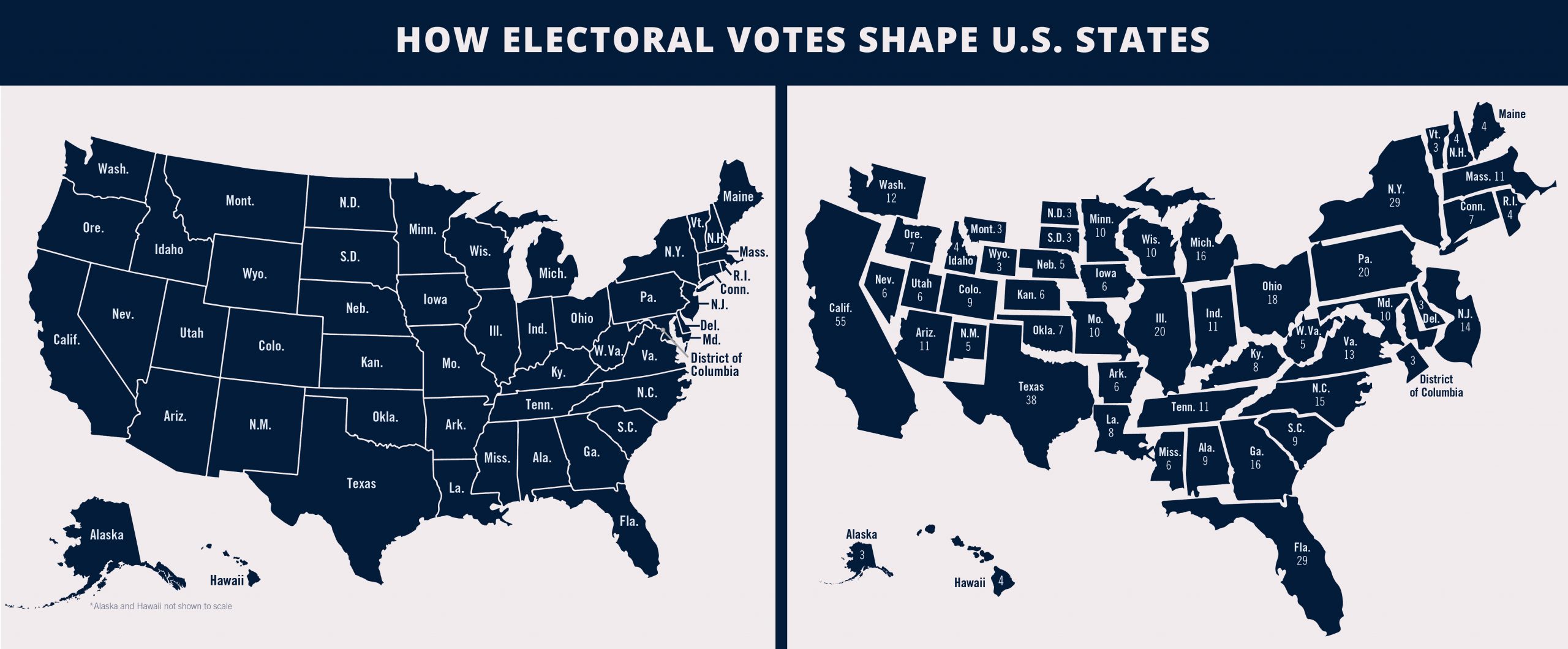

Americans do not vote directly for their president in November, but rather choose members of the Electoral College who then meet in December and cast their votes based on how the majority of voters in their state voted the previous month. The number of electors each state gets is based on population. For example, Florida, with its large population, will determine 29 electoral votes. (That ties with New York for the most after California and Texas.) The presidential candidate who wins states like Florida has a better chance of winning the election, which requires 270 electoral votes.

The map on the left, below, shows the 50 states of the United States as you are used to seeing them. The map on the right shows the states sized according to how many electoral votes they have.

Florida’s special place

Unpredictable and large, like a St. Bernard puppy in the middle of a tea party, Florida is not to be ignored in the presidential election.

It swings between major parties — the state supported Democrat Barack Obama in 2008 and Republican George W. Bush in 2000, for instance. “You don’t want to ignore a state with 29 electoral votes,” says Fordham University political science professor Christina Greer. The fact that the winner in the Sunshine State has won the presidency in every presidential race since 1964 lends it a special mystique.

Florida voters will get two chances to make their mark on the presidential race. First on March 17 in the state primary, when they consider candidates competing for the parties’ nominations, and then on November 3, when they choose from among the two major parties’ nominated candidates and any independent candidate or candidates from other political parties that get listed on the ballot.

“The margin is so razor thin in the state,” Greer said. “Mississippi you can call right now: It’s Republican. With Florida in presidential elections, we don’t know how it’s going to behave.”

In the past two presidential and governors’ races, the margin of victory in Florida has been 1 percentage point. And the state famously ended the 2000 election with a photo finish. It took weeks for Florida officials to recheck ballots and determine that George W. Bush, not Al Gore, was elected president — an outcome that was subsequently confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

This year, the main focus in the Florida primary is on the contested Democratic nomination. Under Florida’s rules, only registered members of a party may vote on March 17. About 37 percent of Florida’s electorate is Democratic, 35 percent is Republican and 27 percent don’t belong to a party, according to Susan MacManus, a political science professor emerita at the University of South Florida and a long-time expert on Florida voting patterns.

Independents, who won’t be able to vote in the March primary but will be a factor in November’s general election, contribute to the volatility of Florida’s voting behavior. Instead of basing decisions on party, they look at the ideology and authenticity of candidates, MacManus said. “They are very down on the two-party system, and they hate polarization,” she said.

While the state is known for its elderly population, that’s not a reflection of the electorate any more. “The idea everyone here is an older person is bunk,” MacManus said. In fact, the youngest three generations (born in 1965 and later) amount to 54 percent of registered voters. Many of the state’s younger voters are independents.

Women will be a big factor in the primary and general elections because they are a majority of the electorate, especially in the Democratic Party. Women make up 58 percent of Florida’s registered Democrats, compared to men’s 39 percent. Voters are diverse in other ways, according to Greer. Latinos, for instance, include Republican-leaning Cuban-Americans and Democratic-leaning Puerto Ricans. The state has “snowbirds” registered to vote — winter residents who travel south each year from areas like the Midwest and Northeast. And Florida boasts rural areas and big cities. “Jacksonville is like the Deep South; Miami is more like Europe,” Greer says.

All that diversity means Florida is where candidates can try out their acts to figure out how to reach a national audience. “We’re sort of the guinea pig for how issues are going to play and how you communicate with different slices of that electorate,” MacManus said.

Banner image: Voters with masks, a sign of caution about the new coronavirus, arrive at Bow Elementary School in Detroit, Michigan, a swing state, for the state primary election on March 10. (© Paul Sancya/AP Images)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP