Mildred and Richard Loving were in love, so they did what so many couples do. They got married.

But it was 1958. And because she was black and he was white, the state of Virginia held that their marriage was illegal.

The Lovings would wage a legal battle all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which would establish that state governments could not bar interracial marriage (individual states set marriage laws in the U.S.).

Mildred and Richard Loving in the offices of their attorney in Alexandria, Virginia (© Francis Miller/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Lovings in love

The Lovings had tied the knot in the District of Columbia (Washington), where interracial marriage was legal at the time. But they lived in Virginia, whose laws made their union a crime. When charged, the Lovings pleaded guilty, and a local judge suspended their one-year prison sentence on the condition that they leave Virginia, which they did, opting to live in the District of Columbia.

A few years later, in 1963, with help from U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy and the American Civil Liberties Union, the couple began their legal journey to the highest court in the land.

Citing the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution’s guarantee to all Americans of equal protection under the law, the Supreme Court overturned the Virginia judge’s decision and declared “racial purity laws” unconstitutional.

“Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote, in a ruling that made interracial marriage legal across the United States.

Open hearts

Lucas Irwin, 35, chef for a Japanese restaurant soon to open in Washington, said, ”I love that they didn’t give up.”

Irwin said that if not for the Lovings, his own white mother and half-Japanese father might not have been able to marry in the 1980s.

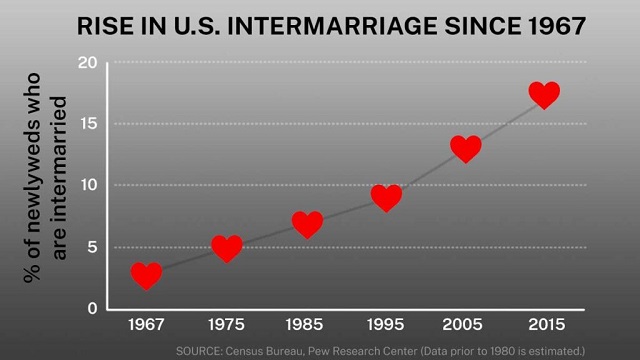

Since the 1967 decision, the United States has seen a steady increase in new marriages between two people from different races — from just 3% to 17% of U.S. weddings, with the fastest growth between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites.

Interracial/ethnic married households have risen in every U.S. state.

Data prior to 1980 is estimated. Sources: Census Bureau, Pew Research Center (State Dept./D. Thompson)

Kim Parker, of the Pew Research Center, says the Loving case “opened the door for people,” ushering in acceptance of such marriages. It’s easier for people to marry outside their race when they won’t face resistance, she said, “whether from their family or their community or just society in general.”

Parker, who directs research on U.S. social trends, said that in addition to the Loving case, two other factors are at play.

The 1965 U.S Immigration and Nationality Act brought millions of Asian and Latin American immigrants to the United States and terminated quotas favoring Europeans. Today’s Americans are more diverse.

And, Parker said, young adults today see interracial marriages as not only acceptable, but good for America.

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP