Water covers more than 70 percent of the planet’s surface. What rules apply in the world’s oceans and seas?

That’s where “freedom of the seas,” a fundamental principle of international law, comes in. It’s important because it affects everything from trade to travel to national security.

For many thousands of years, we have relied on the ocean for sustenance, commerce, exploration, and discovery. A system of international maritime law grew out of a need to balance various interests in these areas, including security, commerce, and resources.

Isn’t water everywhere treated the same?

No, it isn’t. A well-defined body of international law provides a framework for all claims and activities at sea, and the rules vary by location.

Historically, countries made all sorts of claims about the waters along their coastlines and how far out into the ocean they had full sovereignty — in other words, where they could exercise jurisdiction and control in ocean waters much as they did on land.

Nautical maps such as this one, the Bellin map of the world from 1778, were often drawn with the Mercator projection, which meant sailors didn’t need to recalculate their bearings on long voyages. (© Artokoloro Quint Lox Limited/Alamy)

After much debate, the rule emerged that coastal countries could have sovereignty control only in a narrow band of water close to their shoreline, called a “territorial sea.” Beyond that, the “high seas” were declared free for all and belonging to none.

For a long time, territorial seas stretched as far as a state could exercise control from land. That was linked to the distance of a cannon shot fired from shore. This was considered to be about 3 nautical miles (5.6 kilometers). With the negotiation of the 1982 United Nations Law of the Sea Convention, the allowed breadth of a territorial sea claim was extended to 12 nautical miles (22 kilometers).

So what are "international waters" then?

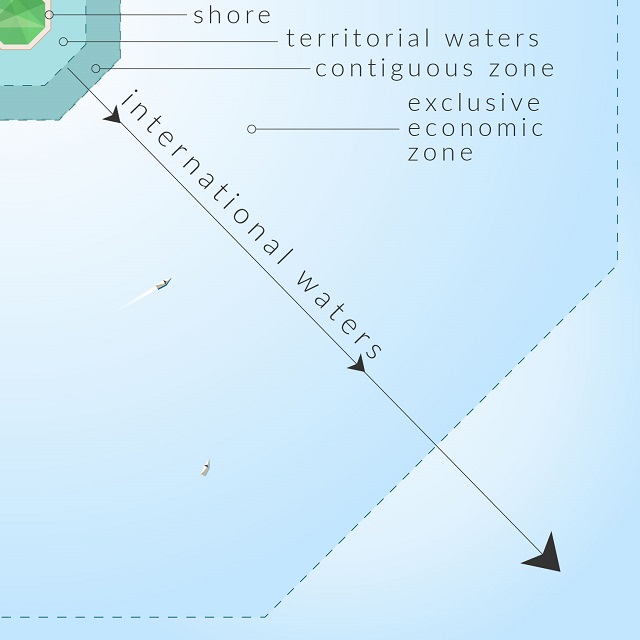

“International waters” isn’t actually a defined term in international law. To varying degrees, depending on location, all ocean waters are international. For example, in a country’s territorial sea, ships of all states enjoy the right of “innocent passage.” But sometimes the term “international waters” is used as an informal shorthand to refer to waters beyond the territorial sea of any state.

A state controls territorial waters up to 12 nautical miles (22 kilometers) from shore, but it can punish violations of its customs, fiscal, immigration and sanitary laws that occur within its territory or territorial waters in a “contiguous zone” up to 24 nautical miles (44 kilometers) out. States have control of all economic resources in the exclusive economic zone, which extends up to 200 nautical miles (370 kilometers) from shore. (State Dept./S. Gemeny Wilkinson)

In these waters, all states enjoy “high seas freedoms” (like the freedoms of navigation and overflight) and other lawful uses of the sea. In general, that means that ships of any country — even a ship flying the flag of a landlocked country — are entitled to exercise those freedoms without interference from any other state. This system of customary international law is reflected in the Law of the Sea Convention.

The Law of the Sea Convention also provides for another important maritime zone: Up to 200 nautical miles (370 kilometers) offshore, a coastal nation can claim an “exclusive economic zone” or EEZ. In that zone, the country has specific rights and jurisdiction for certain limited purposes, including managing fisheries and producing energy from the water and wind. With respect to traditional uses of the ocean, the United States considers that the Law of the Sea Convention reflects customary international law, binding on all countries.

What happens when two countries’ territorial seas or EEZs overlap each other? The two countries need to agree to a maritime boundary that delimits the countries’ claims.

What happens in international waters?

A lot!

About 90,000 commercial vessels transport goods between countries. Also, all countries can lay underwater pipes and cables in international waters. Fisheries in EEZs and on the high seas are also important.

Aerial view of the London Array, an off-shore wind farm in the Thames Estuary in the United Kingdom on February 03, 2014. The world’s largest wind farm is a partnership among RWE, Orsted, Masdar and CDPQ. (© Thomas Trutschel/Photothek/Getty Images)

But even in the territorial sea, all vessels (including military vessels) have the right of innocent passage — they may expeditiously transit territorial waters as long as they do not engage in certain specified activities deemed to disrupt the peace, good order or security of the coastal state. Sometimes, countries make excessive maritime claims that attempt to unlawfully restrict access to or use of the seas.

When this happens, the U.S. Department of State often lodges a protest with the government for making unlawful claims, and works with the country to bring its claim into accordance with international law as reflected in the Law of the Sea Convention. Also, the Department of Defense may conduct a “freedom of navigation operation” to assert the international principle of freedom of the seas. This could mean, for example, sending a naval ship through the waters where a country has made an excessive claim professing to restrict ships’ abilities to exercise their navigational rights and freedoms.

The United States protests excessive maritime claims and conducts freedom of navigation operations on a principled basis regardless of the coastal state, including to protest excessive claims by allies and partners.

This ship was part of a freedom of navigation exercise in the Indian Ocean in March 2018. (U.S. Navy/Morgan K. Nall)

In 2017, the U.S. conducted freedom of navigation operations off the coasts of nearly two dozen states, including Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

OK, so what about pirates?

Piracy in international waters can cause great harm to people and international commerce. Pirate attacks can prevent delivery of humanitarian assistance, raise the costs of traded goods, and endanger ship crews.

U.S. Coast Guard members prepare to board a vessel as part of multinational anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden. (Cassandra Thompson/U.S. Navy/Getty Images)

As the U.N. Law of the Sea Convention reflects, all states have an obligation to cooperate to stop piracy. Any nation can arrest pirates on the high seas and put them on trial. This longstanding principle of international law is a rare example where states enjoy “universal jurisdiction.”

This article was originally published on June 26, 2018.

The original article is here on ShareAmerica.

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP