It was winter, 1982. A plane taking off outside Washington crashed into the Potomac River. In the icy waters, passengers desperately tried to stay afloat.

Suddenly, one woman lost her grip on a rescue line. Standing on the bridge above her, a young man saw her struggle. He dove in and pulled her to safety.

A few weeks later, President Ronald Reagan brought that man to the U.S. Capitol — and in his State of the Union speech, saluted Lenny Skutnik.

“Heroism at its finest,” he said, while politicians from both parties stood and cheered.

As President Obama delivers the 2014 State of the Union address, he may do the same thing. Saluting heroes has become a State of the Union tradition.

Of course, the speech does more than celebrate heroism. It is a report card on how the country has done — and a way to urge tasks for the year ahead.

It is often long. As someone who has contributed to those speeches in the White House and written others like it, let me be clear.

You can learn from it even if you don’t listen to the whole thing.

What Obama will do won’t be so different from what a 15-year-old might do in running to be class president.

How do people writing speeches like the State of the Union go about it? Often speakers and their writers start with five basic questions:

How do we get listeners to pay attention?

What problems lie ahead?

What solutions can we dream up?

How can we inspire listeners so they have faith in our dream?

How can we make listeners not just listen — but act?

You’ll hear them reflected in this year’s State of the Union.

Of course, it’s not just politicians who ask those questions.

In the late 1940s, a young student in divinity school wanted to become a great speaker. Lots of his classmates were trying, too. But this student was so good that on Sunday mornings when it was his turn to give a sermon, his classmates wouldn’t sleep late. They’d get up early and go to listen.

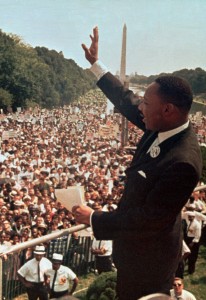

Fifty years ago, that student was on the Mall in Washington, giving a speech answering those same five questions.

“I have a dream today!” Martin Luther King Jr. cried, in a speech that inspired millions around the world — and still does.

Not everyone gets to talk to millions. But as someone who now teaches students how to write and speak, I know that almost everyone can be good at giving a speech. Sometimes, that’s another way to do something heroic.

Is it scary to get up and talk to a group of people? Definitely.

But it’s not as scary as Lenny Skutnik diving into an icy river. And like it was for Martin Luther King Jr., being in school is not too soon to start.

Former chief speechwriter in the White House for Vice President Al Gore, Bob Lehrman is author of The Political Speechwriter’s Companion. He teaches public speaking and speechwriting at American University in Washington.

How to Make a Great Speech

Speechwriters for past presidents say the advice is simple: Know your audience and your message, choose words carefully, and be clear and concise.

Ted Sorensen, speechwriter for President John F. Kennedy:

The first rule of speechwriting is “Less is almost always better than more.” (from his memoir, Counselor)

Joshua Gilder, speechwriter for President Ronald Reagan:

Imagine you’re speaking with family and friends, not to an abstract audience. You’re speaking to Aunt Matilda. You’re trying to think, “What does this mean to her? How will it speak to her needs, concerns, hopes?”

Jeff Shesol, speechwriter for President Bill Clinton:

The first question is not, “What am I going to say?” but “Why am I giving this speech? What am I trying to accomplish?’” Once that goal is clarified, it becomes clearer what to say. There are all sorts of tools and tricks of the trade … but ultimately the most important question is existential: “Why am I here?”

This article originally appeared on the Department of State’s IIP Digital website.

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP