Allan J. Lichtman,Professor of History,American University

The American President

The United States Constitution created a president independent of Congress who was both chief executive and commander in chief of the armed forces. The president would neither be chosen by Congress nor elected directly by the people. Instead an Electoral College of members selected by each state would elect both the president and the vice president. The Electoral College system arose from a compromise between large and small states at the American Constitutional Convention of 1787. Votes in the Electoral College would be roughly apportioned according to the population of each state, which satisfied the interests of the large states. However, no state would have less than three Electoral College votes, which guaranteed that the small states would not be ignored by candidates for the presidency. In 2000, if defeated Democratic candidate Al Gore had won a single additional state with three Electoral College votes, he would have also won the presidency.

Today, the United States is the world’s only superpower, with a military budget nearly equal to the spending of all other nations combined. An American president is not only the most powerful ruler in the world, but arguably the most powerful ruler in the history of the world. Thus the results of an American presidential election have an impact on people across the globe.

Americans formally elect their president every four years on Election Day, designated by Congress as the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. But an American presidential election is a rich pageant that in recent times has begun to unfold a year or two before the November election. Some candidates never stop campaigning. John Edwards, the Democratic vice presidential nominee in 2004, has been campaigning for the 2008 presidential nomination since 2005. Like a well-made play, the American presidential election is a drama in three distinct acts. During Act I, the candidates compete for their party’s nomination. Their objective is to win delegates to the national nominating conventions that are selected in primaries and caucuses held in the American states. During Act II, the parties hold their national conventions, which actually nominate presidential candidates. During Act III, nominated candidates compete in the general election for president of the United States.

Act I: The Primary Campaign

Since the 1970s, voters have selected delegates to the Republican and Democratic nominating conventions mainly in open primary elections held within the states. The states hold three distinctive kinds of primaries. First, most states conduct closed primaries in which only those registered as party members can vote in the party’s primaries. States with closed primaries include Florida, New York, and Pennsylvania. Second, there are open primaries in which voters can participate in the primary regardless of their party affiliation. States with open primaries include Georgia, Indiana, and Ohio, Third, there are mixed primaries in which independent voters, but not members of another party can vote in the primary contest. States with mixed systems include New Hampshire and North Carolina. A few states hold caucuses that differ from primaries by requiring voters to attend party meetings to support the candidate of their choice. Otherwise the rules of inclusion and exclusion are the same. States holding caucuses include Colorado, Iowa, and Minnesota.

The state of Iowa traditionally begins the primary election season when it holds its Republican and Democratic Party caucuses. Shortly thereafter, New Hampshire holds the first primary election. (See Timeline) This gives two small states, with populations that are not representative of the diversity of the nation, considerable influence over the selection of a presidential nominee. In the past thirty years, only Bill Clinton in 1992 has been nominated by the Republican or Democratic parties without winning either the Iowa caucuses or the New Hampshire primary.

In the 1970s, primaries and caucuses were conducted over a period of about five months from February to June. Candidates could build momentum from one contest to the next. In recent elections, however, the primary process has become considerably compressed with states moving their contests earlier in the process to gain more influence over the selection of the nominee. This so-called “front-loading” of primaries is most evident in 2008. This year the Iowa caucuses were conducted on January 3, followed by the New Hampshire primary on January 8, the earliest scheduled times for these primaries in U. S. history. By February 5, 2008, more than half the states will have held their primaries or caucuses, including such large states as California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and New Jersey. (See Timeline) Thus the United States has moved close to establishing, in effect, a national primary for nominating presidential candidates, which heavily favors candidates with high levels of funding and name recognition.

Although the primaries are “front-loaded” to take place early in the election year, the candidates begin competing for their party’s nomination at least a year before the Iowa caucuses take place. Candidates begin campaigning so early because it takes scores of millions and even hundreds of millions of dollars to run a campaign for the Republican or Democratic nomination for president. By the end of 2007, candidates for the major party nominations had already raised substantially more half a billion dollars combined. By the time the primary process is completed, the presidential candidates will likely have raised far more than $1 billion. Candidates can accept matching funds from the federal government for the nominating contest. However, candidates accepting matching funds must also adhere to limits on campaign spending, so leading candidates in 2008 have rejected this option.

Under American election law, corporations cannot contribute to presidential candidates, contributions by individuals are limited to $2,300 for the primary contests, and contributions by Political Action Committees are limited to $5,000. With these restrictions in place, candidates cannot raise the vast sums needed to run a presidential campaign through their own efforts. They rely on events featuring movie stars and other celebrities, and some have effectively used the Internet as a fundraising tool. Candidates also recruit wealthy and well-connected individuals who make a commitment to raise hundreds of thousands and even millions of dollars for the candidate. Despite the prohibition on corporate contributions, corporate executives can contribute large sums to a candidate by “bundling” together many individual contributions of $2,300. In the 2004 election, for example, executives associated with the investment firm of Morgan Stanley contributed $600,000 to the campaign of President George W. Bush.

Although there have been a few exceptions, candidates are not likely to be taken seriously unless they demonstrate significant fundraising capacity and perform well in the polls taken before the primary contests. A little-known candidate who raises unexpectedly large sums of money and does well in the polls can move into the top tier of contenders. This was the case, for example, with former Vermont Governor Howard Dean in the 2004 Democratic pre-primary campaign.

Voters discuss the candidates at a caucus in a small town in Iowa. (© AP Images)

Act II: The Nominating Convention

In the 1830s, the major parties in the United States began holding national conventions to nominate presidential candidates, write a party platform, and establish rules for governing the party. Today, the conventions consist of delegates chosen through state primaries and caucuses, with each state allocated a number of delegates roughly in proportion to its population. Since 1976, however, one candidate from each party has gained a clear majority of the delegates well before the nominating convention. Thus, the conventions have become something of an anti-climax, with the outcome already known. The parties have used the conventions as a media event to present their presidential and vice presidential candidates to the American people and to launch the general election campaign. Little attention is paid to the party platform, because candidates follow their own strategies in running for president and often ignore the party’s official positions. The highlights of recent conventions have been the speeches by the presidential candidates accepting their party’s nomination and setting the themes for the general election campaign.

It is possible, however, that in 2008 one or both parties will have meaningful conventions. If no single candidate sweeps the primary contests, the nomination will be decided by bargaining and deal-making among convention delegates. The 2008 nominating contest is unique in several ways. For the first time in many decades, both major parties have wide open contests for the presidential nomination, with the possibility that the primary vote may splinter among several candidates. In addition, the sitting president or vice president is not included among the candidates seeking the nomination of the party holding the White House, in this case, the Republicans. Since 1956, the presidential party has always nominated either the sitting president (who is eligible to serve only two terms) or vice president. If no candidate enters the Republican or Democratic convention with the majority of delegates needed to secure the nomination, the convention delegates may even turn to a nominee who has not competed in the primaries at all. Adding to the drama for 2008 is the fact that the party conventions are being held especially late this year. The Democratic Convention will be held from Monday, August 25, through Thursday, August 28. The Republican Convention quickly follows. It will be held from Monday, September 1, through Thursday,

Supporters for various candidates gathered at St. Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire. (© AP Images)

Act III: The General Election Campaign

The general election campaign traditionally begins in early September after America’s Labor Day holiday. In the early twentieth century, the political parties conducted the campaign. Today, the candidates conduct their own campaigns with little input from the formal party organization. Since the 1970s, general election campaigns have been funded by the federal government of the United States. The candidates of the Republican and Democratic parties will each receive about $85 million to run their campaigns on the condition that they do not raise private funds. However, it is likely in 2008 that the nominees of both the Republican and Democratic parties will choose not to accept federal funds. This means that they can raise and spend an unlimited amount of private money. Candidates will allocate their funds primarily for television advertising, but also for hiring consultants, and building a national political organization.

In addition to spending by candidates, the political parties can spend unlimited amounts on the presidential campaigns provided that they do not directly coordinate their efforts with the party’s nominees. In 2004, the two major parties spent about $140 million in such independent expenditures. Also, political action committees and other privately organized groups can spend unlimited amounts of money independently in support of their favored candidates. In the 2003-2004 election cycle, independent spending by liberal and conservative groups exceeded $500 million. Overall, spending on the American 2007-2008 general election cycle may approach $3 billion.

Remarkably, this money will be concentrated on a relatively small number of American states. An American president is not elected by the national popular vote, but by electors chosen from each of the individual states, with no state allocated fewer than three Electoral College votes. It takes an outright majority of 270 out of 538 Electoral College votes to win the presidency. Most states have adopted a winner-take-all system in which the winner of the popular vote in a state gains all of the state’s Electoral College votes. In the 2000 presidential election, for example, Republican George W. Bush beat Democrat Al Gore in the state of Florida by 537 votes out 6 million votes cast, but he still won all of Florida’s 25 Electoral College votes, which gained him the presidency with a bare majority of 271 Electoral College votes. Bush won the presidency even though he lost the national popular vote to Gore by some 500,000 votes.

Democratic candidates field questions at the CNN/YouTube debate in South Carolina in July 2007. (© AP Images/Charles Dharapak)

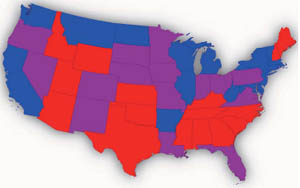

Most American states, however, lean heavily toward either the Democratic Party (blue states) or the Republican Party (red states). As a result, Republicans generally concede such blue states as California and New York to the Democrats, and Democrats generally concede such red states as Utah and Texas to the Republicans. This means that the campaigns are focused on the so-called fifteen to twenty swing states that in a close election could vote either Republican or Democratic. In the 2004 campaign, for example, the candidates and their backers aired very few ads in the nation’s top media markets of New York and California, because both these states were considered safe for the Democrats. Likewise few ads were aired in the major Texas cities of Dallas and Houston, because Texas was considered safe for the Republicans. Yet in just an average week of the 2004 campaign, television viewers in the small city of Reno, Nevada – a swing state – were subjected to 460 Bush campaign commercials and 358 from the Gore campaign. In the 2004 campaign, wrote reporter Tommy Egan of the New York Times, there were “truly two Americas, to borrow a phrase from John Edwards: the swing states, which are fickle and fawned over, and the invisible states, which are predictable and as a result largely ignored.”

The differences between red and blue America are not random, but reflect differences in the electoral base of the two parties. The Republican Party has positioned itself as the party of traditional Christian morality and of private enterprise. The base of the Republican Party consists of white Protestants – especially men – more affluent voters, highly devout Catholics, and married women. The Democratic Party has positioned itself as the party of personal choice on moral issues, the party of the welfare state, and the party that is more sympathetic to labor than employers. Its base consists of African-Americans, Hispanics, Jews, those unaffiliated with a religion, less affluent voters, less devout Catholics, members of labor unions, and single women. Thus states where the voting is dominated by white Protestants tend to be red states, whereas states where the voting is more diverse tend to be blue states, with shades of purple in between. The enclosed map, roughly divides the nation into red, blue and purple or swing states, based on whether the state has two Republican Senators (red states), two Democratic Senators (blue states), or one Republican and one Democratic Senator (purple states). Democratic strength is concentrated is the northeast and west coast and Republican strength is concentrated in the south and the mountain west.

Presidential campaigns consist of media advertising, phone, Internet, and door-to-door contact with voters, speeches, campaign events, interviews, and the presentation of policy positions. However, the centerpiece of both major party campaigns is the televised debates between the candidates, which command national attention. The tradition of conducting televised debates began in 1960 in the contest between Republican Richard Nixon and Democrat John F. Kennedy. In 2004, Bush and Kerry clashed in three debates, one on foreign policy, one on domestic policy, and one in which they answered questions from a group of ordinary citizens in a town-hall meeting format. In 1992, independent candidate Ross Perot became the first and to date only candidate unaffiliated with either the Republican or Democratic parties to participate in a presidential debate. Although America has had a stable two-party system of Democrats and Republicans since the 1850s, independent and third-party candidates have frequently competed for the presidency. Independent candidate Perot won 19% of the popular vote in 1992, the best showing for any candidate from outside the major parties since 1912.

When American voters go to the polls on November 4, 2008, they will have already experienced nearly two years of presidential campaigning. The media assumes that the outcome of the election will be decided by the ups and downs of this marathon campaign. However, larger forces are at work in an American presidential election. My own research suggests that a pragmatic American electorate chooses a president according to the performance of the party holding the White House as measured by the consequential events and episodes of a term – economic boom and bust, foreign policy successes and failures, social unrest, scandal, and policy innovation. If the nation fares well during the term of the incumbent party, that party wins another four years in office; otherwise, the challenging party prevails. I have developed a system for gauging the successes and failures of the party holding the White House and predicting whether that party will win or lose an upcoming election. The enclosed table provides a do-it-yourself scorecard for rating the prospects of the incumbent and challenging parties in this interesting and consequential election year.

Timeline of the American 2008 Presidential election

| 1月3日 | アイオワ州党員集会 |

| 1月8日 | ニューハンプシャー州予備選挙 |

| 1月26 日 | サウスカロライナ州予備選挙 |

| 1月29 日 | フロリダ州予備選挙 |

| 2月5日 | ニューヨーク州、イリノイ州、カリフォルニア州など20 以上の州で「スーパーチューズデ イ」予備選挙 |

| 3月4日 | バーモント州、ロードアイラ ンド州、オハイオ州、テキサス州でミニ「スーパーチュー ズデイ」予備選挙 |

| 4月22 日 | ペンシルバニア州予備選挙 |

| 6月3日 | モンタナ州、サウスダコタ州、ニューメキシコ州で最終の予 備選挙 |

| 8月25–28日 | 民主党全国大会、デンバー(コロラド州) |

| 9月1–4日 | 共和党全国大会、ミネアポリス・セントポール (ミネソタ州) |

| 9月26 日 | 第1回大統領候補討論会(国内政策) |

| 10 月2日 | 副大統領候補討論会 |

| 10 月7日 | 第2回大統領候補討論会(聴衆との質疑応答) |

| 10 月15日 | 第3回大統領候補討論会(外交政策) |

| 11 月4日 | 大統領選挙日 |

| 12 月15日 | 選挙人団の公式投票 |

| 2009年 1月5日 |

副大統領が連邦議会で選挙人 票を開票 |

| 2009年 1月20日 |

新大統領の就任式 |

Political Map of the United States:

Red = Republican states, Blue = Democratic states, Purple = Swing states

* Red states have two Republican senators, blue states have two Democratic senators, Swing states have one Republican and one Democratic senator.

The 13 Keys to the White House

The Keys are statements that favor the re election of the incumbent party. When five or fewer statements are false, the incumbent party wins. When six or more are false, the challenging party wins.

KEY 1 (Party Mandate): After the midterm elections, the incumbent party holds more seats in the U.S. House of Representatives than it did after the previous midterm elections.

KEY 2 (Contest): There is no serious contest for the incumbent party nomination.

KEY 3 (Incumbency): The incumbent party candidate is the sitting president.

KEY 4 (Third party): There is no significant third party or independent campaign.

KEY 5 (Short term economy): The economy is not in recession during the election campaign.

KEY 6 (Long term economy): Real per capita economic growth during the term equals or exceeds mean growth during the previous two terms.

KEY 7 (Policy change): The incumbent administration effects major changes in national policy.

KEY 8 (Social unrest): There is no sustained social unrest during the term.

KEY 9 (Scandal): The incumbent administration is untainted by major scandal.

KEY 10 (Foreign/military failure): The incumbent administration suffers no major failure in foreign or military affairs.

KEY 11 (Foreign/military success): The incumbent administration achieves a major success in foreign or military affairs.

KEY 12 (Incumbent charisma): The incumbent party candidate is charismatic or a national hero.

KEY 13 (Challenger charisma): The challenging party candidate is not charismatic or a national hero.

Allan Lichtman, Professor of History at American University in Washington, DC, is the author of many books and scholarly articles on the presidency of the United States and on voting rights. His most recent book is White Protestant Nation: The Rise of the American Conservative Movement, forthcoming in June. He has given political commentary on a number of television programs, including NBC, CBS, ABC, CNN, C-SPAN, CNN, FOX, MSNBC, BBC, PBS, and numerous other broadcasting outlets internationally. He has testified before the United States Commission on Civil Rights regarding voting systems and voting rights, and before committees of the U.S. House of Representatives and the United States Senate.

Professor Lichtman received his undergraduate degree from Brandeis University, Phi Beta Kappa, Magna Cum Laude. He earned his doctorate at Harvard University as a Graduate Prize Fellow.

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP