“Hey, Dad,” one of my most outgoing students says when she sees me. Her name is Sophia*, and she’s very proud to be a lesbian. This bright senior, who is brimming with leadership qualities, will literally turn around with glee when she hears the word “lesbian.” She often parks her Subaru next to my car and says, “Did you see my lesbian car?” The joke is that Subaru has a reputation for being the car of choice for lesbians in the United States.

The school where I teach is an extraordinarily liberal private school located in central New Jersey. Perhaps because of that and the nature of the subject I teach—theatre—there are usually several LGBTQIA+ students in my classes.

Ten years ago, I taught at a mid-size state school in Pennsylvania, and I distinctly recall a gay student of mine named Jonathan. He was not a theatre major at first and was not very open about his sexuality until he joined our department. After he started hanging out with his fellow thespians, including a pansexual male and an engaged lesbian couple, he realized the other students genuinely wanted each other to succeed and welcomed everyone regardless of race, gender, or sexual preference. Soon, Jonathan began to feel comfortable and could simply be himself.

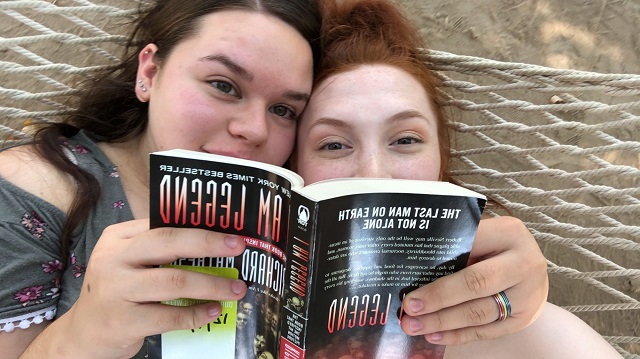

Sophia and her girlfriend reading a book for class on the campus hammocks.

In this open and safe environment, the students and I often made self-deprecating jokes and laughed at ourselves. Though it may sound silly, the truth is that this kind of humor can be used as a method to monitor the social environment for cues regarding the degree to which a person who is telling the joke is being accepted. Humor was one of the ways we showed students from marginalized communities that we have had similar experiences so we understood who they were and were their allies.

Jonathan graduated about five years ago, just when universities across the United States began putting more resources into support systems for the LGBTQIA+ community on campuses. My current school now has a diversity office in the student center, and their door is open to anyone. Gender-neutral bathrooms have been installed in many buildings, and the university’s website has a map indicating where they are located. Some other resources on our campus are the SafeZone Program (a campus-wide voluntary program that creates allies, supports, and resources for the LGBTQIA+ community) and Spectrum (an organization dedicated to bringing together the campus community on the topics of homosexuality, bisexuality, transgenderism, the intersexed, and those that are questioning their sexuality). These resources are not unique to my school and exist at most universities.

Jasper (left), Daniel (center), and Morgan (right) taking a friendly picture after a long day of classes.

In contrast to Jonathan, Eric, who graduated about seven years ago, never discussed his sexuality. It was not until a few years ago that I found out he was gay. Even in our department, he did not have allies with whom he could be open about who he was. Once he graduated and moved to New York City, he was finally able to meet some allies and began to feel more comfortable about himself. Soon afterward, he started posting more LGBTQIA+ related content on Facebook and let the world know who he really is.

A current student of mine, Michelle, is non-binary and uses they/them/theirs pronouns. They say, “Everyone at the school is free to be themselves, express themselves, and take pride in who they are.” This is such a simple thing for many non-LGBTQIA+ people, but sometimes, for people like Michelle, Eric, and Jonathan, such fundamental human rights can be denied by hurtful acts of intolerance and ignorance. When asked how they felt about the openness and acceptance of LGBTQIA+ students off campus, Michelle said, “My experience in New Jersey may be different than others, but to me, I have found a great level of acceptance and met a wide range of people on the LGBTQIA+ spectrum. While college may have provided some of those people, I also met them just by growing up and experiencing the state I live in.”

Sophia and I painting a piece of the scenery for an upcoming musical at the school.

My experience was similar to Michelle’s. My family and I lived in the capital city of New Jersey for ten years. Our townhouse was on a treelined street where we had a gay couple on either side of our house, a lesbian couple across the street, and another lesbian couple with kids. During Gay Pride Month, there were at least six rainbow flags flown outside of various houses within 100 meters of my house. The owners of these houses were the kindest and most considerate neighbors we had. While this street may be a special case, places like this do exist as openly and proudly as any other neighborhood in the U.S.

Sophia’s girlfriend Melanie says, “If you are thinking of applying to schools in the U.S., make sure to look up their policies on diversity and inclusion and find out if they have any specific policies relating to LGBTQIA+ students.” Melanie suggests that a good way to gauge a college is to read what students are saying about it online. Once you get to the school, find a diversity office dedicated to LGBTQIA+ students and LGBTQIA+ student organizations. You can always ask people who work at these offices to connect you to other LGBTQIA+ students so you can hear what the current students have to say about the school and surrounding area.

In the United States, professors can be your best allies. Sophia grew up in a household where her father was very conservative, and he still does not recognize her sexuality. This is probably why she jokingly refers to me as “Dad.” Thus, during the college years for students like Sophia, professors and advisors can become parental figures who care about them unconditionally. When asked about her school and professors, Michelle said, “Everyone here is welcoming, and they encourage everyone to discover themselves and be who they are unapologetically. I am not afraid of scorn from my peers or educators. If anything, I’m more open with them than anyone else. Your educators are your friends, and they want you to succeed and be happy, no matter what.”

*Names are not the students’ real names.

Banner image: Sophia (center) and Morgan (top left) with their friends while working on a theatre production for school.

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP