Being LGBTQI+ was different in 1995 than it is today. Back then there was more fear and anxiety around the issue of coming out (that is, of letting others know about your sexual identity) or of being outed (that is, having someone else divulge your sexual identity without your permission). In 1995, the U.S. military’s policy called “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was in effect, which kept LGBTQI+ service members from being open about their identity. For many people, and not just American military members, the consequences of outing were real: coming out or being outed could cost a person their job, home, family, or friends.

Although it was necessarily a time of concealment for many, it was also a time of camaraderie and inclusion. The LGBTQI+ community in Okinawa in the mid-90s was vibrant and welcoming. Japanese and American LGBTQI+ people came together with a strong sense of unity and friendship. Without cellphones, apps, or the internet, the only way we could find each other and build our community was by maintaining strong personal connections. And that, in fact, was the secret to getting into Heaven.

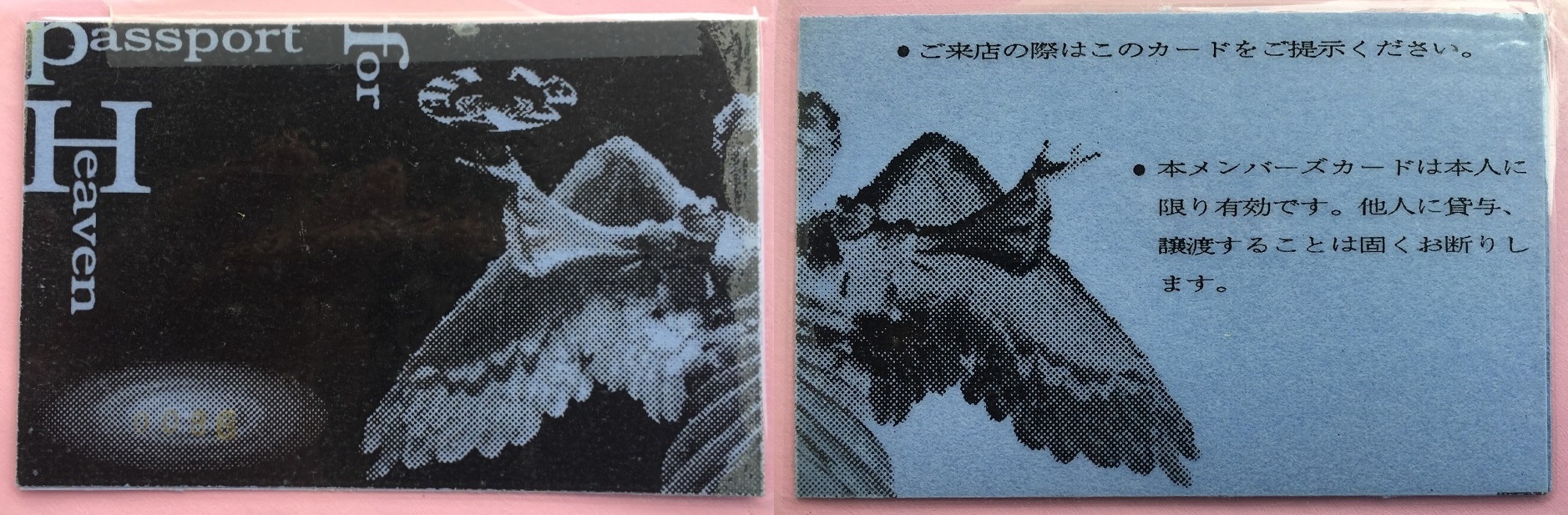

Passport for “Heaven”

Heaven was an LGBTQI+ party that happened once a month in the basement of an old building at the Koza intersection on Gate 2 Street in Okinawa City. The building is long gone—torn down to make way for Koza Music Town. To get to Heaven you walked down a narrow staircase from the street. At the bottom of the stairs there was a person waiting to check your Passport. If you had one, they’d pull back a heavy black velvet curtain to reveal a makeshift bar area with old sofas and chairs pushed against the walls. This room was connected to an empty room that served as a dance floor. It was small and cramped. There were no windows and no decorations. Still, you were in Heaven. You could dance with whomever you wanted, flirt, hold their hand, share a kiss, and just be yourself. It’s hard to overstate just how rare it was be able to do this in “public” in Okinawa at the time—and how free it felt.

The only way to get into Heaven for the first time was to be taken down the stairs by someone with a Passport. Curious people who heard the music from the street and ventured down the stairs to see what was going on were turned away. Only if someone with a Passport vouched for you would you then be given your own Passport. Without someone to vouch for you—even if you were really LGBTQI+—you could not get in. It was due to this level of strictness and concern for people’s privacy that allowed the people in Heaven to feel comfortable and safe.

Consul General Robert Koepcke (left) and consulate staff at Pink Dot Okinawa in 2018.

Times certainly have changed for LGBTQI+ people in Okinawa. As the Public Affairs Officer at the U.S. Consulate General in Naha, I’m proud that each year the Consulate hosts a booth at Okinawa’s largest LGBTQI+ Pride event, Pink Dot. Pink Dot is a celebration, full of fun and laughter. But I smile all the wider knowing that the Consulate is there because the United States stands in solidarity with human rights defenders all over the world who strive to guarantee the rights of LGBTQI+ individuals to live with dignity and without fear of reprisal.

Sometimes at Pink Dot I meet friends I’ve known since I first lived on Okinawa back in the 1990s and early 2000s. We invariably talk about just how happy and amazed we are at the progress that’s been made in both Japanese and U.S. societies since the time when we felt lucky to be let into places like Heaven once a month. Although there is still work to be done, the level of acceptance of LGBTQI+ individuals that I experience today would have been virtually unthinkable 25 years ago. But in one way, what was true then is still true today—without friends there can be no Heaven.

A scene from Pink Dot Okinawa in 2017.

Banner image: Richard Roberts (second from right) and consulate staff at their booth at Pink Dot Okinawa in 2017.

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP