Each of the U.S. presidential libraries and museums offers insights into the personality of a former U.S. leader.

It’s why scholars and tourists have flocked to these sites, administered by the National Archives, ever since the first presidential library, in honor of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, opened in 1941.

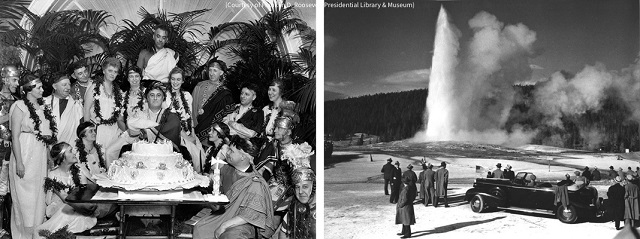

Left: President Franklin D. Roosevelt (center) celebrates his birthday in 1934 as his wife, Eleanor, stands above his right shoulder. Right: Roosevelt views Old Faithful at Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming in 1937. (Courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum)

Located in former presidents’ home states, the complexes honor the legacies of President Herbert Hoover through President George W. Bush (with President Barack Obama’s facility under construction in Chicago and President Donald Trump’s not yet underway). Each collection offers visitors the chance to better understand events that shaped America and the world.

Popular features

At Boston’s John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, visitors discover how Kennedy (1961–1963) directly engaged the American people via unedited, live press conferences on television, said library director Alan Price.

“The public loved his press conferences,” Price said, which were usually held every 16 days and averaged 18 million viewers. Library visitors can view clips from these exchanges, with Kennedy’s witticisms enlivening his banter with reporters.

In Austin, Texas, the most popular exhibit commemorating President Lyndon B. Johnson (1963–1969) is “undoubtedly our re-creation of the Oval Office,” said director Mark Lawrence. Visitors remark on the distinctly 1960s feel of the space — the antiquated phones and televisions and the ubiquitous ashtrays.

Martin Luther King Jr. talks with President Lyndon B. Johnson. (Yoichi Okamoto/LBJ Library)

Visitors can hear recordings of Johnson’s phone calls, which capture him in relatively casual, unguarded moments. One memorable conversation, from early 1965, features Johnson talking with Martin Luther King Jr. about the strategy that would lead to the passage of the Voting Rights Act in March of that year.

Glimpses of real men

The Abilene, Kansas, library for President Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953–1961) features his “in case of failure” message — written when he served as supreme Allied commander in Europe during World War II.

Handwritten by then-General Eisenhower on the eve of the Normandy invasion, the message expresses his acceptance of responsibility should the invasion fail, library director Dawn Hammatt said. “He ends the note by stating, ‘The troops, the air, and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.'”

And at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum in Simi Valley, California, there are two writings on display that reveal the “essence” of Reagan (1981–1989), according to director Duke Blackwood.

President Ronald Reagan talks to reporters aboard Air Force One. (Courtesy Ronald Reagan Library)

One is Reagan’s entry in his diary about surviving an attempted assassination. (“Getting shot hurts,” he wryly observed.) Although admitting he initially “felt hatred for the mixed-up young man” who shot him, Reagan recalls a biblical passage about lost sheep and forgives his assailant.

President Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan walk together at Camp David in Maryland. (Courtesy Ronald Reagan Library)

The other document is Reagan’s handwritten letter to the American people announcing that he has Alzheimer’s disease, diagnosed four years after he left office. The letter brought important awareness to the debilitating disease, Blackwood said, and showed Reagan’s determination to face it with grace.

Banner image: Curator Dave Powers holds a portrait of President John F. Kennedy in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum storage section in the Federal Records Center. (Allan Goodrich/JFK Library)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP