On Labor Day, which falls on the first Monday in September in the United States, many workers took a well-earned rest and all Americans reflected on the importance of workers’ rights.

This year, Labor Day was an especially fitting time to honor the resilient workers who have helped America stay strong during the coronavirus pandemic. They have educated children, cared for the sick and equipped Americans with the necessities of daily life. Here are a few of their stories.

‘You have to care’

James Daniels (left) delivers mail. Daniels stops for a lunch break (right) while on his route. (© Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images)

Every day, before he suits up and opens his front door to deliver mail for the U.S. Postal Service, James Daniels says several prayers. For 16 years, Daniels, 59, has worked the same route — delivering to 808 customers in San Clemente, California. His customers depend on him to deliver their bills, medicine and other essentials.

“That’s their lives I put in their mailboxes,” Daniels says. “If you’re doing this job here, you have to care.”

Now that COVID-19 has changed daily life, Daniels finds himself busier than usual, delivering “tons” of packages for people working from home or staying home due to a quarantine order. He’s dropped off items as large as mattresses, furniture and wagons.

It’s more work, but it’s “good work,” he says. “What I mean by good work is it’s helping people. It’s helping people get through this COVID-19 thing.”

He stays safe by cleaning his mail truck with disinfectant. He wears a mask and gloves while on his route. He showers and washes his uniform at the end of each day.

The customers along Daniels’ route look out for him. They keep him hydrated with gifts of water and Gatorade. They have given him so many face masks that he’s started turning them down. He did accept one hand-sewn mask with pictures of mail trucks on it from a long-time customer. He calls her “the nicest lady in the whole wide world” and reports that she told him she made the mask because “we don’t want nothing to happen to you, James. We really don’t.”

‘Get really creative’

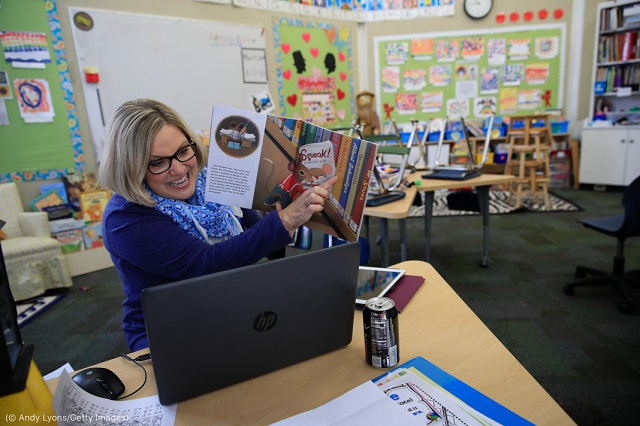

Joanne Collins Brock teaches second grade from her empty classroom at St. Francis School in Goshen, Kentucky. (© Andy Lyons/Getty Images)

With the help of cockroaches, a peacock fascinator, a giant cutout of herself and plenty of creativity, Joanne Collins Brock is teaching second graders in the middle of a pandemic.

Brock, 54, teaches language arts and social studies at St. Francis School in Goshen, Kentucky, near Louisville. Earlier in the year, the initial panic of switching to virtual classrooms was followed by teaching the school’s 370 students some new rules. Brock constantly reminded the noisy students to mute their microphones.

Brock visited the school and used her camera to show students their cubby holes and other features of the classroom they were missing. She has been using games, not worksheets, to teach reading. And she has led her students as they each decorated a sock and performed a puppet show.

“We just had to get really creative,” says Brock, who has taught for 18 years. At the end of online classes, she says, the second graders are reluctant to sign off, so they often eat lunch together by video.

She worries that some children struggle with the lack of social interaction or support. But it helps, she says, that “it’s a close-knit group.” The students and their families also have worked to give Brock a boost. One mother made a larger-than-life cardboard cutout of Brock and arranged for individual students to have their photos taken with it.

Brock’s classroom pets are Madagascar hissing cockroaches, which are related to praying mantises. They help her teach about life cycles and help students overcome any fear of insects. The bugs compete in the second graders’ annual roach race, held the Thursday before the Kentucky Derby. (The students name the insects with humorous imitations of famous Americans’ real names. Among this year’s names were references to a well-known singer, a state governor and even Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.)

While the real Kentucky Derby was postponed, Brock donned a turquoise fascinator with peacock feathers to call the roach race on her classroom’s track. “I’d announce it just like at Churchill Downs: ‘They’re coming around the corner, Roach Bader Ginsburg is ahead by an antenna,’” Brock says.

Like other teachers, Brock is getting ready to return to the classroom. She has ordered face shields and masks with clear vinyl for herself, since it’s important for students to see her smiling to reinforce their efforts or scowling to rein in the rambunctious. “That way, they can get the whole teacher look — you know that look,” she says.

‘We are still safe’

On an April day when Annie’s Paramount Steakhouse in Washington is closed, Sara Rivas works alone to arrange toilet paper for later pickup. (© Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP Images)

When the economy first shut down, Sara Rivas happily spent more time with her husband, 9-year-old daughter and 2-year-old son. But staying home from her job at Annie’s Paramount Steakhouse in Washington got “real, real boring.”

Since the restaurant reopened in June, she’s back at work as a prep cook and occasional host, seeing regular customers return and reconnecting with co-workers. “I am thankful to be working,” says Rivas, whose husband has seen the hours at his construction job reduced. “Thanks to God we are still safe.”

“Everything has been different, but we are good,” says Rivas, who’s worked at the restaurant for 12 years. “We follow all the rules.”

The new landscape includes wearing masks and gloves … and selling stacks of toilet paper.

‘Lemonade out of the lemons’

Siena Farms owner Chris Kurth waters crops. (© Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe/Getty Images)

Chris Kurth, 45, toiled at Siena Farms for years, hoping for a break. Some years there was money left to plow back into the business. Other years, not.

Then COVID-19 hit. His 14-year-old daughter’s school closed and she couldn’t see her friends. His wife, celebrated chef Ana Sortun, shuttered her three Boston-area restaurants and retooled them for carryout, which meant buying fewer farm vegetables.

“It felt like it was time to make lemonade out of the lemons that rolled into our lives,” says Kurth, who named the Sudbury, Massachusetts, farm after his daughter, Siena.

As people began cooking at home more, they were frustrated by the empty shelves at their local supermarkets. Soon, word got out about the Siena Farms’ Community Supported Agriculture program, which sells produce directly to consumers who sign up for regular purchases. People flocked to the farm. In most years, about 400 customers get boxes of vegetables delivered from the farm, but this year 1,700 families have signed up. Kurth quickly bought items such as fresh bread and strawberry jam from other farmers, planted more crops and bought equipment to increase his deliveries and efficiency.

By the end of July, Kurth had tripled the income he earned for the entire year of 2019. The community part of his business now accounts for 90%, up from 33% before the pandemic. Kurth knows many businesses are struggling this year and acknowledges that his family is especially lucky. The difficult times nudged his farm in a direction he had wanted to go, and the deliveries to the community are now bankrolling his entire operation.

“It’s truly a dream come true,” he says.

Banner image: Nurse Michele Younkin (standing) comforts Romelia Navarro at the bedside of her husband, Antonio, at St. Jude Medical Center's COVID-19 unit in Fullerton, California. (© Jae C. Hong/AP Images)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP