Skateboarding is one of the four new sports included in the Olympic program for Tokyo, along with karate, sport climbing, and surfing. What does it mean to skateboarders that their sport is going to be part of the Olympics for the first time ever? Also, as a sport that originated in the United States, what kind of impact has skateboarding had on American society, particularly youth culture? To find out the answers to these questions, I interviewed Dr. Neftalie Williams, a former semi-professional skateboarder who became a scholar focusing on the impact of skateboarding on young people. Williams is currently a University of Southern California Provost’s Postdoctoral Scholar at the Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism and a Yale Schwarzman Center Visiting Fellow in Race, Culture and Community.

Transcending Boundaries

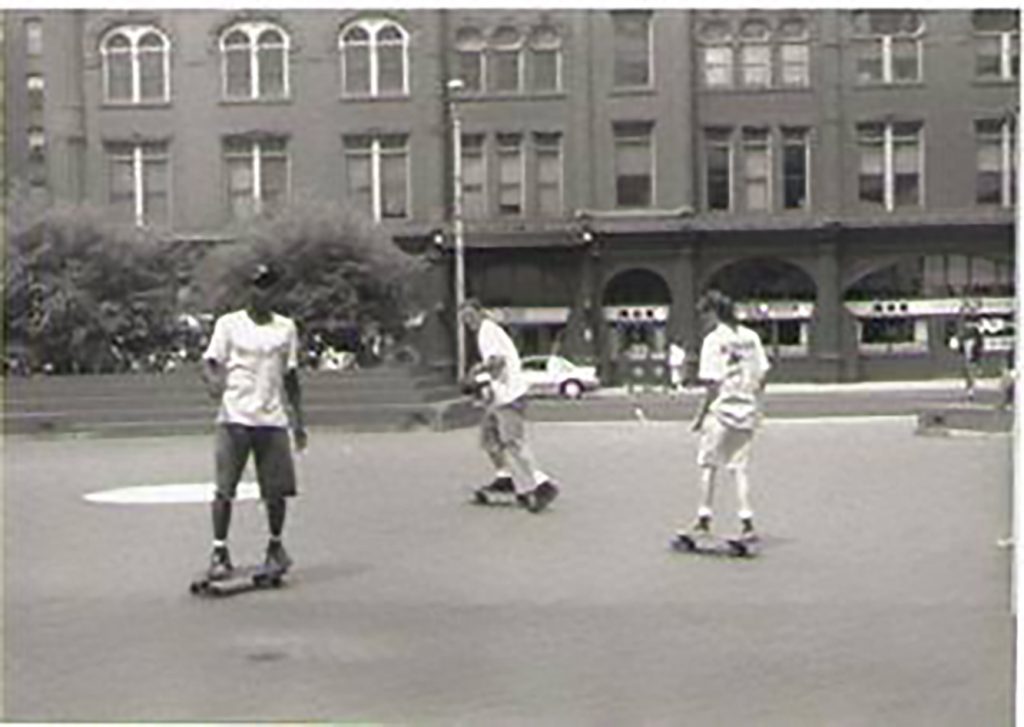

Williams was born and raised in Springfield, Massachusetts, and grew up surrounded by people from diverse backgrounds. “It was the love of skateboarding that crossed those boundaries,” he said. When Williams turned 15, his mother gave him his first skateboard. “What was unique about skateboarding was that because there were no rules and because it was not an organized sport, it became a democratic affair. Everyone who was interested in skateboarding got together, and all of us started teaching each other. It was experiential learning.”

Neftalie Williams (left) began skateboarding as a teenager in Springfield, Massachusetts.

From Skateboarding to “Affecting Skateboarding”

In his late teens, Williams further developed his skateboarding skills and moved to California, where he was discovered by a company called Volcom, which later became his official sponsor. As a semi-professional skateboarder, he realized he wanted to utilize skateboarding as a vehicle for youth development and community building. "I conducted my first skateboarding camp when I was 21 years old,” he said. “The reason I did that was because I wanted more kids to skate. I’d already started thinking beyond being my own career as a skateboarder. I wanted to teach kids.”

Even though Williams was skateboarding at the highest level, what meant most to him was building a community and camaraderie. “I always looked at skateboarding in a collective manner,” he said. “Then I realized my mission was not to only be great skateboarder; my mission was to affect skateboarding.”

Sports Diplomacy

In 2016, Williams conducted a Sports Envoy Program organized by the U.S. Embassy in the Netherlands and funded by the Department of State's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs where he introduced the concept of skateboarding as a tool for cultural diplomacy. “I worked with young Syrian refugees who had been granted asylum in the Netherlands,” he said. “Thanks to the Department of State, it was exactly the vision I wanted. It was not solely focused on inspiring young people to be elite athletes, but to actually understand skateboarding culture and see the most important element of skateboarding culture—building community.”

Williams explained that when people skateboard, they become part of a global community. “In the Netherlands, I talked to high schoolers at an international school about what it means to have immigrants in their country,” he said. “Then the young immigrants and refugees and Dutch students got together to learn to skateboard. What skateboarding allowed the young Dutch students to see was that when they were all skateboarding, the young Syrian students were just young students like them.” More recently Williams worked on skate diplomacy in Cambodia.

Williams teaches young Cambodian skaters as part of a Department of State sports diplomacy program.

Skateboarding and Community

Williams also emphasized that skateboarders need to have media content creation skills nowadays to be able to promote themselves. For that, he said, creating a strong team of people with photography and videography skills is crucial. “Because skateboarding culture has always been marginalized and always on the fringe, we have our own way of expressing ourselves and creating media. No one becomes a pro skater without their friends being videographers and photographers.”

However, even though the advancement of technology has changed the way skaters promote themselves, they still have to be good human beings, Williams said. “They could be good skaters, but what are their personalities like? How are they presenting themselves online? What are they like in the real world? Because in the real world, when you go on tours and you’re in the van with people, you want to be with excellent skaters but you also want to be with great human beings.”

“Obstacles Become Opportunities”

Williams said that when people skateboard, their vision of their surroundings changes. “You have a level of freedom and autonomy and move faster than the world around you,” he explained. “Your relationship to your surroundings changes. What we want is for people to reimagine their environments. Obstacles become opportunities. That is a key thing that happens in skateboarding.”

Williams demonstrates his skateboarding skills. (photo by Rachele Honcharik)

Skateboarding at the Tokyo Olympics

Williams said he is very excited about the potential and possibility of Olympic skateboarders. “The Olympics is a very big stage for people who might not have really seen skateboarders at that level of athleticism,” he said. “Even if skaters don’t win medals, that doesn’t mean they are less valid or important. What is most important for me is that those athletes will be able to reflect upon the benefits of the skateboarding culture in a public forum.”

Williams is particularly fascinated with the idea that skateboarding is both individual and collective. “It is the pursuit of individual goals and expression, but it can also be celebrated by the collectives around you,” he said. “You rise, we all rise.”

Banner image: Portrait of Neftalie Williams with his "The Nation Skate" photo exhibition at the John F. Kennedy Center for Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. in 2015. (photo by Ryan Kellman)

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP