When Americans stream into polling places November 3, the presidential election will be the main attraction. But Election Day in the United States will give voters the chance to weigh in on so much more.

Leaders will be chosen at the federal, state and local levels. And policy decisions will be put directly to a vote under a ballot initiative system that allows citizens in many states to decide on questions that can affect their daily lives.

Beyond choosing a president

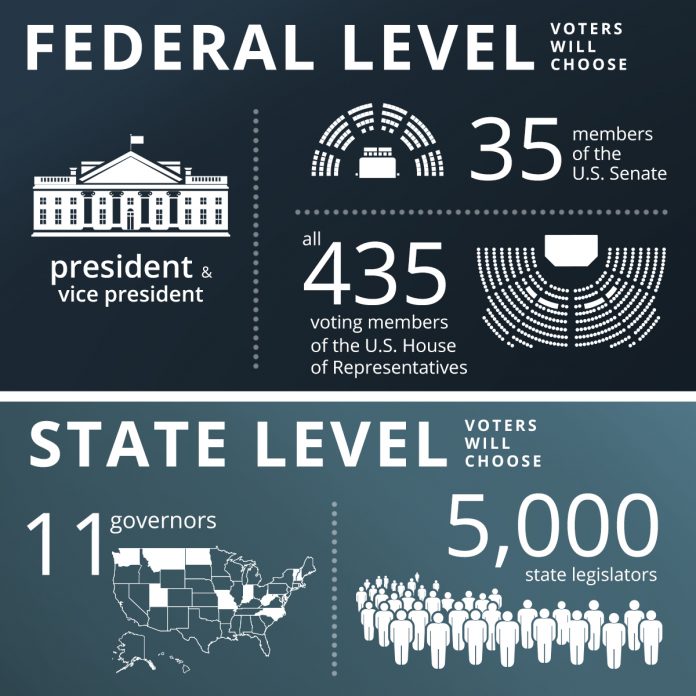

This year at the federal level, voters will choose a U.S. president, 35 members of the U.S. Senate and all 435 voting members of the U.S. House of Representatives. (Senators serve for six years, so each election cycle about one-third of the 100 seats are up for a vote. Every representative’s seat is up for election every two years, on the even years.)

At the state level, 11 governorships are up for grabs this year, as are more than 5,000 state legislature seats.

(State Dept./B. Insley)

“What a president does on a day-to-day basis doesn’t affect people’s lives like local and state governments do,” said Stella Rouse, a government professor at the University of Maryland and director of the Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement. “Most of the laws that are passed are passed at the state level.” That’s why this year’s state elections are particularly important.

Moreover, newly elected state legislators will take part in redoing the lines that determine congressional districts. It is an every-10-year overhaul (based on a decennial census) that can help one party or another. “It really matters who controls the state legislature,” says Josh Chafetz, a law professor at Cornell University.

State elected officials are important when gridlock among elected officials in Washington slows federal lawmaking. “We should look to the states,” Rouse said. “They are filling the void in passing policies” in areas such as immigration.

Local officials like mayors and city council members get more consideration during a presidential election year, when voter turnout is high. That’s good because they govern issues close to voters’ hearts, like which streets get repaired, whether improvements are made to local schools and whether the regional economy gets a boost.

Policy by the people

Twenty-four states also let voters partly bypass the elected officials and have their say directly on issues through ballot initiatives. Initiatives became popular in 1978, when California voters slashed property taxes under something called Proposition 13. Other measures that have passed in some states tightened gun laws, raised the minimum wage for workers and created independent commissions to oversee redistricting.

Rouse said the theory behind ballot initiatives is to give more power to the people. But the costs of mounting ballot campaigns — including paying lawyers to draw up the wording and buying advertisements — have gotten so high they are less accessible today to individuals.

How will the winners govern?

The U.S. system of sharing power between different levels of government is based in the Constitution, which divides power between state and federal officials, with the states sharing their authority with local government.

“There are some things you want to coordinate at the national level,” Chafetz said, like national defense. “There are plenty of other policies [for which] there’s no reason they should be uniform everywhere. What federalism does, in theory, is allow both.”

Voters get to choose, for instance, whether they want a high level of services and higher taxes in their state, while voters in another state can pick the opposite.

Federalism can lead to conflict between state and national officeholders but also leads to better policies, according to Rouse. “Dividing power and the constant push and pull between national and state governments is a good thing,” she said. “When you go through that process, what comes out as policy is about as good as you can get.”

COMMENTS0

LEAVE A COMMENT

TOP